A recent Harvard Medical School study published on November 3 in Science Immunology may explain why exercise leads to inflammation. Researchers have been intrigued by this connection since the early 1900s when a study found increased white blood cells in Boston marathon runners after the race.

In a study with mice, researchers found that exercise’s benefits may partly be due to the immune system. They discovered that when muscles become inflamed during exercise, special immune cells called Tregs help boost muscle energy use and overall endurance. These Tregs, known for fighting inflammation in autoimmune diseases, now appear to play a role in the immune response during exercise. While this study used mice and not humans, it’s a significant step in understanding the cellular and molecular changes during training and its health benefits.

Exercise is known to protect against heart disease, lower diabetes risk, and help prevent dementia. But how does it make us healthy? This question has puzzled researchers for a while. The recent discoveries are part of ongoing efforts to figure out how exercise works at a molecular level, and understanding the role of the immune system is just one piece of this puzzle.

Study first author Kent Langston, a postdoctoral researcher in the Mathis lab, said, “We’ve known for a long time that physical exertion causes inflammation, but we don’t fully understand the immune processes involved. Our study shows, at very high resolution, what T cells do at the site where exercise occurs, in the muscle.”

Previous exercise research examined how hormones affect organs like the heart and lungs. This new study delves into what happens in the muscles during exercise, revealing an immune response cascade.

Exercise is known to damage muscles, causing inflammation temporarily. It also increases the activity of genes controlling muscle structure, metabolism, and mitochondria, which provide energy for cells during exercise.

In this study, researchers examined muscle cells from mice that ran on a treadmill either once or regularly, comparing them to cells from inactive mice. The active mice’s muscle cells displayed signs of inflammation, with increased gene activity for metabolic processes and higher levels of inflammation-promoting chemicals, including interferon.

Both groups of exercising mice had more Treg cells in their muscles, which reduced exercise-induced inflammation. These changes didn’t occur in the inactive mice.

However, the metabolic and performance benefits of exercise were only seen in the regularly exercising mice. Tregs in this group not only reduced inflammation and muscle damage caused by training but also improved muscle metabolism and performance. This matches what we know in humans, where single workouts don’t lead to significant performance gains; it’s consistent exercise over time that brings benefits.

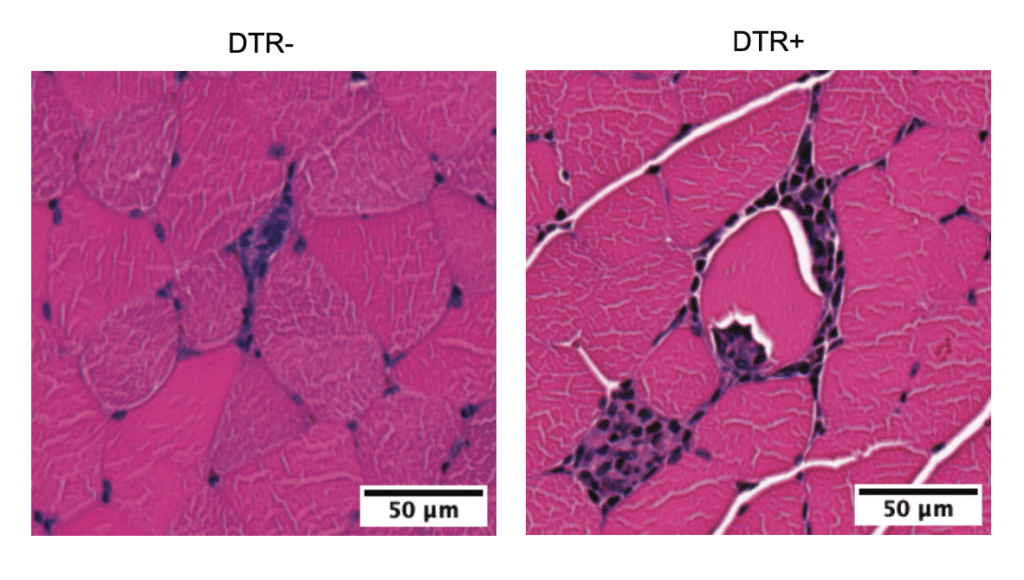

Further analysis confirmed that Tregs were responsible for these broader benefits. Mice without Tregs had unchecked muscle inflammation, an accumulation of inflammation-promoting cells in their leg muscles, and abnormal muscle cell metabolism.

More importantly, animals lacking Tregs did not adapt to increasing exercise demands over time like mice with intact Tregs did. They did not derive the same whole-body benefits from exercise and had diminished aerobic fitness.

These animals’ muscles also had excessive interferon, a known driver of inflammation. Further analyses revealed that interferon acts directly on muscle fibers to alter mitochondrial function and limit energy production. Blocking interferon prevented metabolic abnormalities and improved aerobic fitness in mice lacking Tregs.

“The villain here is interferon,” Langston said. “In the absence of guardian Tregs to counter it, interferon went on to cause uncontrolled damage.”

Interferon is known to promote chronic inflammation, a process that underlies many chronic diseases and age-related conditions, and has become a tantalizing target for therapies aimed at reducing inflammation. Tregs have also captured the attention of scientists and industry as treatments for various immunologic conditions marked by abnormal inflammation.

The study gives us a glimpse into how exercise reduces inflammation at the cellular level and highlights the importance of using our body’s immune defenses.

Researchers are working on interventions that target Tregs for specific immune-related diseases. While treating conditions caused by abnormal inflammation requires precise therapies, exercise is another natural way to combat inflammation.

The research suggests exercise can enhance the body’s immune responses to reduce inflammation. While they studied muscle, exercise also boosts Treg activity elsewhere.

This study highlights the role of the immune system, specifically regulatory T cells, in responding to inflammation caused by exercise and maintaining muscle health. It shows that the best metabolic and performance benefits from exercise come with regular physical activity over time, confirming the importance of consistent training for substantial health improvements.

Additionally, the research suggests that exercise can naturally boost the body’s immune responses to reduce inflammation, potentially benefiting other body parts. These findings offer valuable insights into how exercise affects the immune system and emphasize the importance of using movement to enhance our immune defenses.

While ongoing efforts are to create treatments targeting regulatory T cells for specific immune-related diseases, exercise remains a natural and accessible way to combat inflammation.

Journal reference:

- P. Kent Langston, Yizhi Sun, et al., Regulatory T cells shield muscle mitochondria from interferon-γ–mediated damage to promote the beneficial effects of exercise. Science Immunology. DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.adi5377.