Researchers at the Salk Institute have found that even killer T cells, specialized immune cells that tirelessly seek and destroy cancer cells, can become exhausted. This exhaustion hinders their ability to fight cancer effectively.

The study revealed a connection between this exhaustion and the body’s “fight-or-flight” stress response in different types of cancer, both in mice and human tissues. Interestingly, the researchers also discovered that this interaction between killer T cells and stress hormones can be blocked using beta-blocker drugs, commonly used to manage human blood pressure and heart rate. This breakthrough could lead to the development of more resilient cancer-fighting T cells.

The results, published in Nature on September 20, 2023, reveal a fresh connection between the body’s stress response and how the immune system deals with cancer. Moreover, they highlight the potential of combining beta-blocker medications with current immunotherapies to enhance cancer treatment by reinforcing killer T-cell activity.

Professor Susan Kaech, senior author and director of Salk’s NOMIS Center for Immunobiology and Microbial Pathogenesis, said, “There is no question immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer patient treatment, but there are many patients for whom it’s ineffective. Finding that our nervous system can suppress the function of cancer-destroying immune cells opens up new ways to think about rejuvenating T cells in tumors.”

The sympathetic nervous system handles our stress response, like in a “fight-or-flight” situation. Until now, we didn’t know much about how these nerves affect our immune response to infections or cancer.

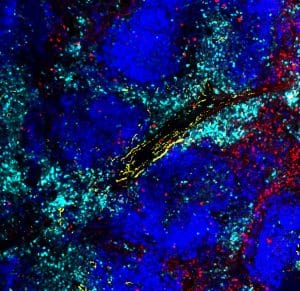

The researchers looked at the sympathetic nerves that connect to our organs and release a hormone called noradrenaline, a stress hormone. They studied this in mice and human tissue samples, using different models for cancer and chronic illnesses to figure out how and when these nerves impact killer T cells.

The study discovered that sympathetic nerves were releasing a hormone called noradrenaline. This hormone was attached to killer T cells through a receptor called ADRB1. Exhausted killer T cells had more ADRB1 receptors than their active counterparts, allowing them to respond to the noradrenaline released by the nerves.

The researchers tried two approaches to block the interaction between noradrenaline and ADRB1 to see if they could prevent killer T-cell exhaustion. They either removed ADRB1 completely or impaired its function using beta-blocker drugs. Both methods resulted in more effective killer T cells that were better at destroying cancer cells.

Interestingly, the exhausted T cells didn’t just sense the nerves from a distance; they gathered around them in tissues. Surprisingly, the ADRB1 receptor provided instructions to the T cells, telling them to move closer to the nerves. This, in turn, suppressed their function, making them less effective at fighting cancer.

First author Anna-Maria Globig, a postdoctoral researcher in Kaech’s lab, said, “The innervation of tumors is an understudied area of tumor immunology. Our study has uncovered that nerves contribute to T cell exhaustion in tumors, where T cells become worn out and less powerful in their fight against the tumor over time. Suppose we can unravel how nerves suppress the body’s immune response to cancer and why the exhausted T cells move toward the nerves. In that case, we can target this process therapeutically.”

The researchers, led by Kaech, want to dig deeper into why stress negatively affects our health by studying exhausted killer T cells.

They’ve identified a new pathway that beta-blockers can target. This could help create more potent killer T cells that don’t get exhausted and can fight cancer more effectively, as explained by Globig.

Since beta-blockers are already used in clinics, the team plans to test this approach on lung cancer patients soon. They’ll collaborate with doctors to study more human cancer samples, giving them more data to support the idea that beta-blockers can be effective in cancer treatment.

Journal Reference:

- Globig, AM., Zhao, S., Roginsky, J., et al. The β1-adrenergic receptor links sympathetic nerves to T cell exhaustion. Nature. 10.1038/s41586-023-06568-6.