Scientists have created an enzyme that works like scissors to weaken cancer cells’ defenses. This enzyme can break down a protective layer that cancer cells use to hide from the body’s defenses and treatments. This breakthrough could help make cancer cells easier to target and treat effectively.

Researchers at Stanford University have crafted a special molecule that can remove deceptive molecules known as mucins from cancer cells, a development with significant implications for future cancer treatment. Mucins, which are sugar-coated proteins designed to protect our bodies, are misused by cancer cells for their survival.

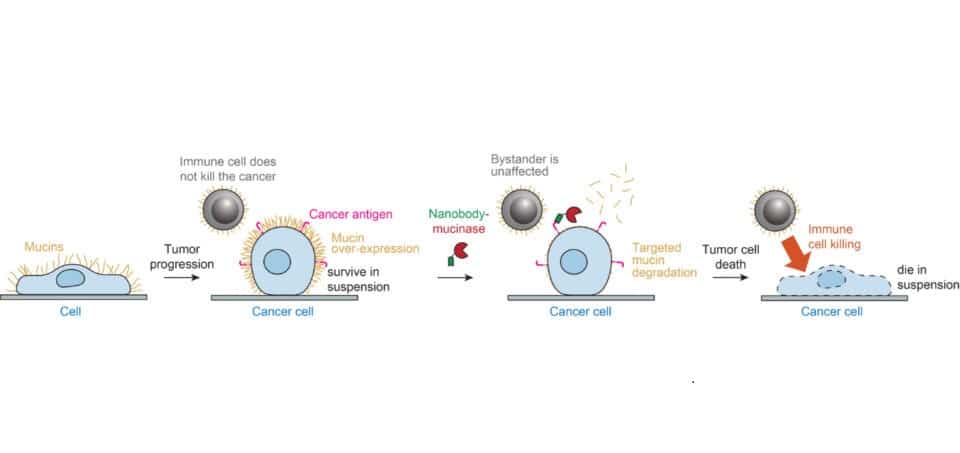

The novel tool, resembling enzyme-based scissors, targets explicitly and eliminates mucins on cancer cells using a protein cutter (protease) and a marker-like antibody piece. Successfully tested on lab-grown human cancer cells and mice with breast and lung cancer, the tool led to tumor reduction and extended survival.

Published in Nature Biotechnology on August 3, the discovery could also have applications in addressing respiratory issues and viruses. However, caution is needed as mucins exist on all mammal cells, potentially posing challenges if widely removed.

Senior author Carolyn Bertozzi, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass professor in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, said, “We found that we could target this mucinase to cancer cells, use it to remove mucins from those cancer cells, and there was a therapeutic benefit.”

Even though mucins are generally helpful, cancer cells misuse them for their gain. Mucins are proteins that do good things in our body, like making protective mucus and guarding us from harmful things. However, Cancer causes them to act in harmful ways. Graduate scholar Gabrielle “Gabby” Tender co-lead author, said, “Mucins do important jobs in our body, like making mucus in our lungs and gut, and protecting us from germs. Cancer uses mucins to grow and spread.”

This study looked at two ways mucins help Cancer grow. First, they help cancer cells survive when floating around without sticking to anything. Bertozzi said, “Cancer spreads by breaking off, floating to other body parts, and growing there. Regular cells can’t survive while floating, but those changed by mucins can.”

Second, mucins attach to immune system checkpoint receptors. These receptors check cells in the body like guard dogs. Some cancer cells put mucins with specific sugars on their surfaces. These sugars attach firmly to the receptors. When this sugary mucin binds to the receptors, it tells the immune system to ignore the cancer cell, stopping the body from attacking it. “This makes immune cells think the cancer is okay instead of killing it,” explained Tender.

The scientists made a special molecule with two parts joined together. The first part comes from bacteria and is called mucinase. It cuts mucin. The second part is a tiny piece that only sticks to cancer cells. The tiny amount guides the mucins to the cancer cell, like parking a car. This finding is part of a bigger project to bring molecules close together for specific reactions.

The scientists used a mucinase called StcE from a bacteria called E. coli. They already know how bacterial enzymes help treat Cancer in some cases, but they never tried mucinosis before. They tested the StcE mucinase in mice. It worked, but it cut too much mucin everywhere. So, they needed to aim it only at the tumor’s mucins.

In the past, scientists connected antibodies to enzymes to target them. But it made the enzyme less effective. The team worked on the StcE mucinase and made a version called eStcE. This version works the way they wanted.

The team chose a nanobody called 5F7 because it matches an antigen (HER2) linked to various cancers like breast and ovarian. They made different versions of the combo with eStcE mucin cutter and 5F7 nanobody, testing for performance. The best combo, called αHER2-eStcE, was selected. They then tested this combo on cancer cells in dishes and mice with lung and breast cancer simulations. The αHER2-eStcE combo effectively killed cancer cells and slowed growth in mice, showing promise for cancer treatment.

The scientists want to make a similarly targeted mucin-cutter using a human-based enzyme to reduce the risk of unwanted immune reactions. While more research is needed, this study is a significant advancement in cancer research. Before, there wasn’t much we could do about mucins in Cancer, but now there’s hope with this new approach.

Journal Reference:

- Pedram, K., Shon, D.J., Tender, G.S. et al. Design of a mucin-selective protease for targeted degradation of cancer-associated mucins. Nature Biotechnology. DOI: 10.1038/s41587-023-01840-6.