According to a new study, a special kind of antibody produced by llamas could help fight against COVID-19. The antibody binds firmly to an essential protein on the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. This protein, called the spike protein, allows the infection to break into host cells. Beginning tests indicate that the antibody blocks viruses that display this spike protein from infecting cells in culture.

When llamas’ immune systems recognize foreign invaders, for example, bacteria and viruses, these animals (and different camelids, for instance, alpacas) produce two types of antibodies: one that is similar to human antibodies and another that is just about a quarter of the size. These smaller ones, called single-domain antibodies or nanobodies, can be nebulized and utilized in an inhaler.

Daniel Wrapp, a graduate student in McLellan’s lab and co-first author of the paper said, “That makes them potentially really interesting as a drug for a respiratory pathogen because you’re delivering it right to the site of infection.”

Scientists gathered blood ample and isolated antibodies that bound to each version of the spike protein. One indicated the real promise in halting an infection that showcases spike proteins from SARS-CoV-1 from contaminating cells in culture.

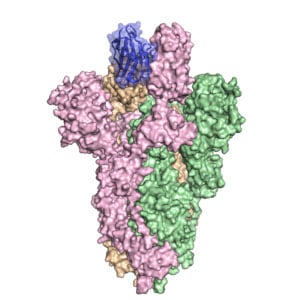

The antibody called VHH-72 bound tightly to spike proteins on SARS-CoV-1. It also prevents a pseudotyped virus — a virus that can’t make people sick and has been genetically engineered to display copies of the SARS-CoV-1 spike protein on its surface — from infecting cells.

At the point when SARS-CoV-2 emerged and triggered the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists pondered whether the antibody they found for SARS-CoV-1 would likewise be viable against its viral cousin.

They found that it bound to SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein as well, but weakly. To make it bound more effectively, they engineered two copies of VHH-72, which they at that point demonstrated neutralizes a pseudotyped virus sporting spike proteins from SARS-CoV-2.

This is the first known antibody that kills both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2.

Dorien De Vlieger, a postdoctoral scientist at Ghent University’s Vlaams Institute for Biotechnology (VIB) said, “I thought this would be a small side project. Now the scientific impact of this project became bigger than I could ever expect. It’s amazing how unpredictable viruses can be.”

Other co-authors of the study include Gretel M. Torres, Wander Van Breedam, Kenny Roose, Loes van Schie, Markus Hoffmann, Stefan Pöhlmann, Barney S. Graham and Nico Callewaert.

The study is conducted in collaboration between the University of Texas at Austin, the National Institutes of Health, and Ghent University in Belgium.

Journal Reference:

- The finalized paper will appear here on May 5: https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(20)30494-3