Children who are overweight or obese are more likely to become obese adults and have an increased risk of poorer health outcomes in later life, including diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and overall mortality. Although the rise in the incidence of childhood obesity appears to have plateaued in some developed nations, the condition is still estimated to affect 124 million children worldwide.

Past studies have connected being overweight with scoring lower on different proportions of executive function, an umbrella term for several functions, for example, self-control, decision-making, working memory, and reaction to rewards. Extensively, official capacity alludes to a lot of procedures that empower planning, problem-solving, flexible reasoning, and regulation of behaviors and emotions.

To examine if this link existed in children, scientists at the University of Cambridge and Yale University analyzed data from 2,700 children between the ages of 9-11 years. They found that childhood obesity was linked to structural differences in key brain regions. The children were recruited as part of the National Institutes of Health Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (NIH ABCD) Study.

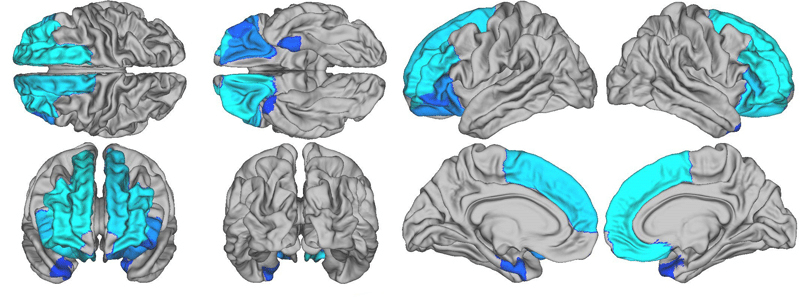

Specifically, scientists examined the thickness of the cortex, the outer layer of the brain – our so-called ‘grey matter’ – and compared it to each child’s body mass index (BMI). They discovered an association between increased BMI and significant reductions in the average (mean) thickness of the cortex, as well as thinning in the pre-frontal region of the cortex, an area associated with cognitive control. This relationship remained after accounting for factors including age, sex, race, parental education, household income, and birth weight.

What’s more, scientists also discovered that increased BMI was associated with poorer performance at tests to measure executive function.

The study’s first author Dr. Lisa Ronan from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, said, “We saw very clear differences in brain structure between children who were obese and children who were a healthy weight. It’s important to stress that the data does not show changes over time, so we cannot say whether being obese has changed the structure of these children’s brains or whether innate differences in their brains lead them to become obese.”

The study is published in the journal Cerebral Cortex.