If women don’t have had children before their mid-30s, there are fewer chances of having children after that period. But scientists at the Princeton University have discovered a drug that expands egg suitability in worms, notwithstanding when taken halfway through the fertile window, which could hypothetically stretch out women’ fertility by three to six years.

Ageing in women means losing reproductive ability in mid-adulthood. As early as the mid-30s, women start to experience declines in fertility, there are more chances of miscarriage and maternal age-related birth defects. All these problems are thought to be caused by declining egg quality, rather than a lack of eggs.

Coleen Murphy from Princeton University reviewed the literature on aging and on reproductive health about a decade ago. She found that this particular question — how to maintain egg quality with age — had been overlooked by researchers from different fields.

Photo byDenise Applewhite, Office of Communications

Murphy specializes in using a microscopic worm, Caenorhabditis elegans, to study longevity. These worms have a large number of indistinguishable qualities from people, including those that drive the maturing procedures of their three-week-long lives. Quite a while back, specialists in her lab found that C. elegans not just displays a comparable midlife decrease in multiplication, yet in addition that their unfertilized eggs (oocytes) indicated comparable decreases in quality with age to women eggs.

When scientists found the answer, they later decided to focus on the genes and proteins that are more common in healthy, young eggs than aging ones. They recently decided to try the opposite approach — investigate why some proteins are “downregulated,” or less common, in the lower-quality oocytes.

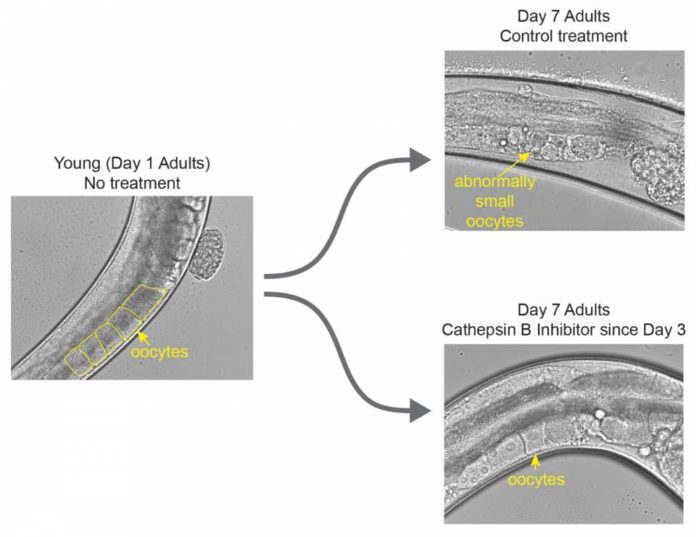

Scientists recently examined one downregulated gathering of proteins, cathepsin B proteases, that are uncommon in astounding eggs and more typical in eggs that have started corrupting with age. The presence of medications that piece these correct proteins gave a chance to test their belongings.

Murphy said, “There were at least three possibilities. One, that this was just an inert marker of good oocytes, in which case, there would be no effect from blocking these proteins. Two, their expression increased as a compensatory mechanism to fight the effects of aging, in which case, blocking the proteins’ activity would make things even worse. Or three, that these proteins normally increase in old, poor-quality oocytes and are part of the problem — in which case, their loss would help slow age-related decline.”

At the point when Templeman managed the medication, she found that the appropriate response was behind entryway number three: The treated worms still had solid eggs long after the control aggregate did not.

They had controlled the medication toward the start of the worms’ conceptive window, the likeness pubescence, so despite the fact that the medication worked, it wouldn’t be useful to grown-up ladies.

Murphy said, “What you want is a drug [that] you could give to a woman in her mid-30s, and it would still preserve the oocytes that she has.”

Scientists waited until halfway through the worms’ reproductive period before she gave them the drug. And It worked beautifully.

The results were better than they had hoped, showing that even a late administration of the drug could extend the worms’ egg quality. Another experiment that knocked out the cathepsin B genes entirely succeeded in extending worms’ fertility by about 10 percent. If applied to humans.

However, its bit difficult to believe that microscopic warm could have anything in common with mammals. They thus were delighted to discover a cattle breeding study that found the cathepsin B proteins that affect the C. elegans oocytes play the same role in cows.

Sean Curran, an associate professor of biogerontology at the University of Southern California Leonard Davis School said, “This study is significant on several fronts. A reproductive decline is a hallmark of aging, but despite its prevalence, interventions to slow the loss of reproductive capacity are lacking. Dr. Murphy and colleagues have capitalized on their rich data sets to identify a pharmacological target to quell the loss of reproductive decline that comes with age.”

The results are published online in the journal Cell.