Scientists using NASA’s Hubble and the retired Spitzer space telescopes observed two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star. Located almost 218 light-years away in the constellation Lyra, these planets are unlike any planet in our solar system.

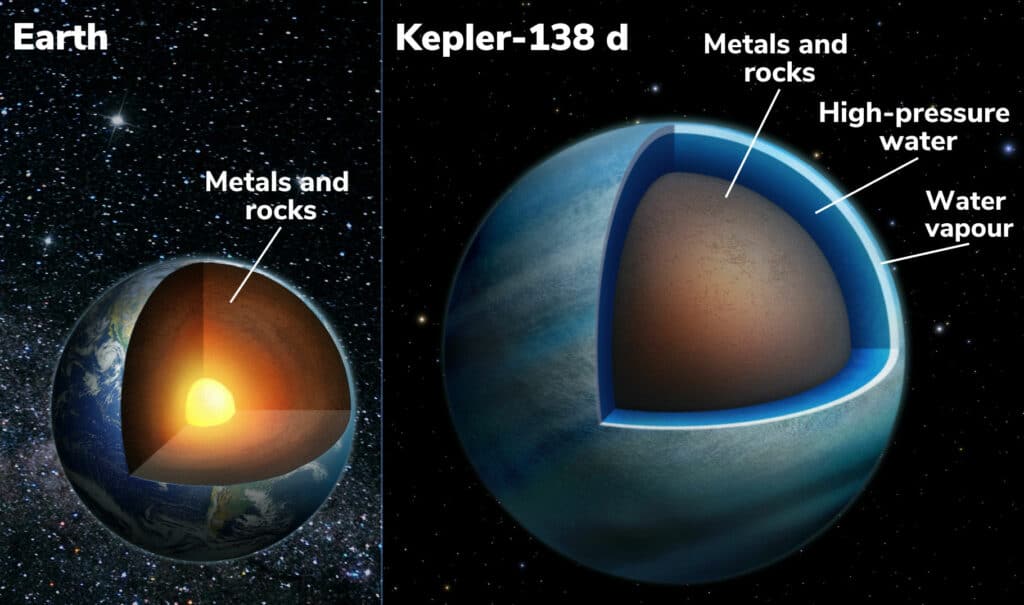

The detailed observations showed that the planets- Kepler-138 c and Kepler-138 d- are water worlds. Despite having volumes more than three times that of Earth and masses twice as big, planets c and d have much lower densities than Earth.

This is unexpected considering that the majority of planets that are only marginally larger than Earth that have been thoroughly researched thus far all appeared to be rocky worlds similar to ours. According to scientists, several of the icy moons in the outer solar system that also has a rocky core and is mainly made of water would be the most comparable.

Water wasn’t explicitly found at Kepler-138 c and d. Still, by comparing the planets’ sizes and masses to theoretical predictions, astronomers have concluded that up to half of their content should be composed of substances heavier than hydrogen or helium but lighter than rock (which constitute the bulk of gas giant planets like Jupiter). Water is the most prevalent of these potential materials.

Björn Benneke, study co-author and professor of astrophysics at the University of Montreal, said, “We previously thought that planets that were a bit larger than Earth were big balls of metal and rock, like scaled-up versions of Earth, and that’s why we called them super-Earths. However, we have now shown that these two planets, Kepler-138 c and d, are quite different and that a big fraction of their entire volume is likely composed of water. It is the best evidence yet for water worlds, a type of planet astronomers theorized to exist for a long time.”

Caroline Piaulet of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets at the University of Montreal said, “The planets may not have oceans like those on Earth directly at the planet’s surface. The temperature in Kepler-138 d’s atmosphere is likely above the boiling point of water, and we expect a thick, dense atmosphere made of steam on this planet. Only under that steam atmosphere, there could potentially be liquid water at high pressure, or even water in another phase that occurs at high pressures called a supercritical fluid.”

Kepler-138 c and d, two potential water worlds, are not found in the habitable zone, which is the region surrounding a star where temperatures permit liquid water to exist on the surface of a rocky planet. However, scientists also discovered proof of a brand-new planet in the system, Kepler-138 e, in the habitable zone in the Hubble and Spitzer data.

This recently discovered planet takes 38 days to complete an orbit and is smaller and farther from its star than the other three. However, since it doesn’t appear to transit its host star, the nature of this extra planet is still unknown. Astronomers may have measured the exoplanet’s size by observing its transit.

With Kepler-138 e in the picture, the masses of the previously identified planets were once more determined using the transit timing-variation method. This technique involves monitoring minute changes in the precise moments of the planets’ transits in front of their star brought on by the gravitational pull of other nearby planets.

Another surprise for the scientists was that, contrary to what was previously believed, the two water worlds Kepler-138 c and d are actually “twin” planets, nearly identical in size and mass. On the other hand, Kepler-138 b, the planet closer in, is proven to be a tiny Mars-mass planet and one of the tiniest exoplanets discovered so far.

Benneke said, “As our instruments and techniques become sensitive enough to find and study planets that are farther from their stars, we might start finding many more of these water worlds.”

Journal Reference:

- Piaulet, C., Benneke, B., Almenara, J.M. et al. Evidence for the volatile-rich composition of a 1.5-Earth-radius planet. Nat Astron (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-022-01835-4