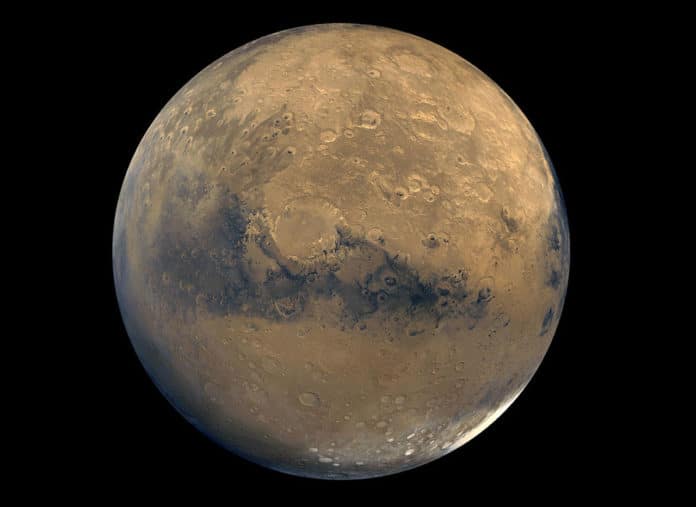

Billions of years ago, Mars is believed to be a warm and wet world that could have supported microbial life in some regions. Geological evidence suggests that rivers and oceans may have been prominent features in its early history.

The planet is smaller than Earth, with less gravity and a thinner atmosphere. The theory suggests that over time, as liquid water evaporated, more and more of it escaped into space.

A new study funded by NASA has shown that a large quantity of Mar’s water- between 30 and 99%- is trapped in its crust rather than having escaped into space. This study challenges the current theory that the water escaped into space.

While some of this water undeniably disappeared from Mars via atmospheric escape, the new findings conclude it does not account for most of its water loss.

For this study, scientists used a wealth of cross-mission data archived in NASA’s Planetary Data System (PDS). They then integrated data from multiple NASA Mars Exploration Program missions and meteorite lab work.

Scientists then studied the quantity of water on the Red Planet over time in all its forms (vapor, liquid, and ice) and the chemical composition of the planet’s current atmosphere and crust, looking particularly at the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen (D/H).

Water consists of hydrogen and oxygen. But, not all hydrogen atoms are the same: some have just a single proton while a tiny fraction (about 0.02%) exists as deuterium, or so-called “heavy” hydrogen, which has a proton and a neutron.

The lighter-weight hydrogen gets away from the planet’s gravity into space more efficiently than its denser counterpart. Along these lines, the loss of a planet’s water by means of the upper atmosphere would leave a revealing sign on the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen in the planet’s atmosphere: There would be a very large amount of deuterium gave up.

The loss of water through the atmosphere doesn’t thoroughly explain both the observed deuterium-to-hydrogen signal in the Martian atmosphere and large amounts of water in the past.

When water interacts with rock, chemical weathering forms clays and other hydrous minerals that contain water as part of their mineral structure. This process occurs on Earth as well as on Mars. On Earth, old crust continually melts into the mantle and forms a new crust at plate boundaries, recycling water and other molecules back into the atmosphere through volcanism. However, Mars has no tectonic plates, so the “drying” of the surface, once it occurs, is permanent.

Lead scientist for NASA’s Mars Exploration Program at the agency’s headquarters in Washington said, “The hydrated materials on our planet are continually recycled through plate tectonics. Because we have measurements from multiple spacecraft, we can see that Mars doesn’t recycle, and so water is now locked up in the crust or been lost to space.”

The results were presented at the 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) by lead author and Caltech Ph.D. candidate Eva Scheller along with co-authors Bethany Ehlmann, professor of planetary science at Caltech and associate director for the Keck Institute for Space Studies; Yuk Yung, professor of planetary science at Caltech and senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Danica Adams, Caltech graduate student; and Renyu Hu, JPL research scientist.