A UCLA-led study explains why immunotherapy works for tumors that spread to the brain but not for glioblastoma, a type of brain cancer.

When cancer spreads to the brain from other body parts, immunotherapy boosts the immune response, but this doesn’t happen with glioblastoma. Glioblastoma doesn’t activate the immune system effectively because the process works better in lymph nodes outside the brain.

Immunotherapy has been successful for some cancers that spread to the brain, like melanoma. This new research, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, could improve brain tumor immunotherapy and guide the development of better treatments.

The study’s senior author, Robert Prins, a professor of molecular and medical pharmacology and neurosurgery at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said, “If we’re going to try to develop new therapies for solid tumors, like glioblastoma, which are not typically responsive, we need to understand the tumor types that are responsive, and learn the mechanisms by which that happens,”

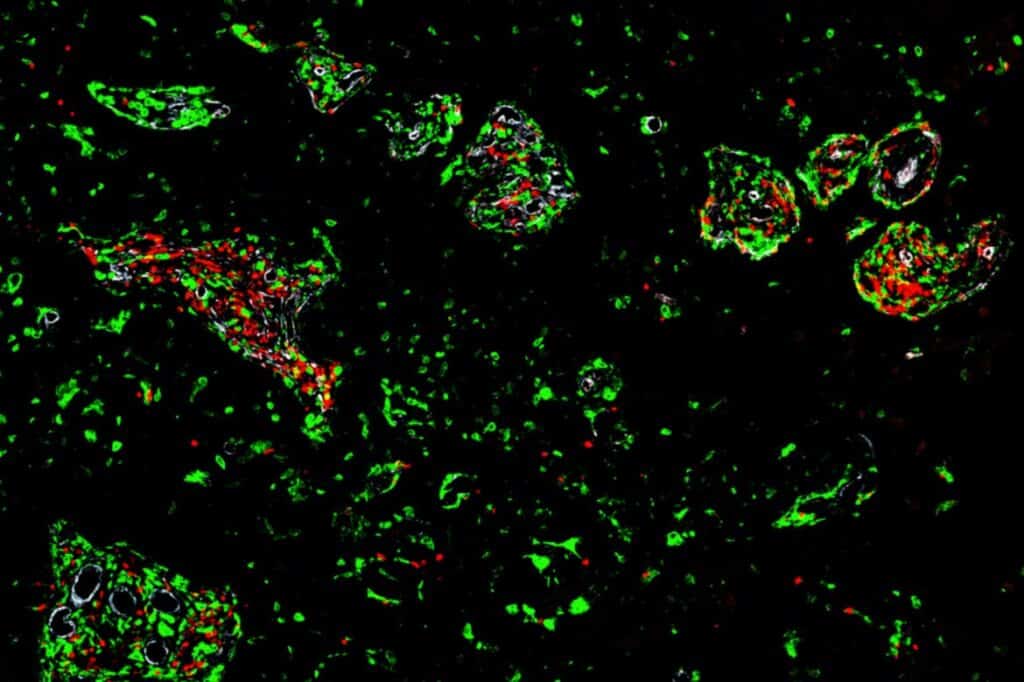

The researchers studied the immune cells of nine people with brain tumors that had spread from other parts of their bodies. These patients received resistant checkpoint blockade treatment, which activates the immune system to fight cancer. They compared these patients to 19 others with brain tumors who hadn’t received this treatment.

They used single-cell RNA sequencing to examine these cells’ genetic material. Then, they compared this data to previous studies on 25 recurrent glioblastoma tumors to understand how the treatment affected T cells.

They wanted to determine which immune cells changed when the treatment worked better. They discovered that in tumors that had spread to the brain, the T cells had unique traits that helped them fight the tumors in the brain. This was likely because the T cells got better instructions outside of the brain before entering it.

Before going to the brain, T cells get activated in the lymph nodes. During this process, another type of immune cell called dendritic cells tells the T cells about the tumor so they can attack it. However, this activation process only works well when doctors try to use immune checkpoint blockade to treat glioblastoma.

The researchers also found that specific tired T cells were linked to more prolonged survival in people whose cancer had spread to the brain.

They discovered a big difference in how brain tumors respond to immunotherapy. More T cells were present in brain tumors after immunotherapy for cancers that had spread to the brain compared to glioblastoma patients. This finding suggests that improving the activation of T cells by dendritic cells could be a potential treatment.

In future studies, they plan to analyze data from a larger group of people with melanoma that spread to the brain.

Journal Reference:

- Lu Sun, Jenny C. Kienzler et al., Immune checkpoint blockade induces distinct alterations in the microenvironments of primary and metastatic brain tumors. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. DOI: 10.1172/JCI169314.