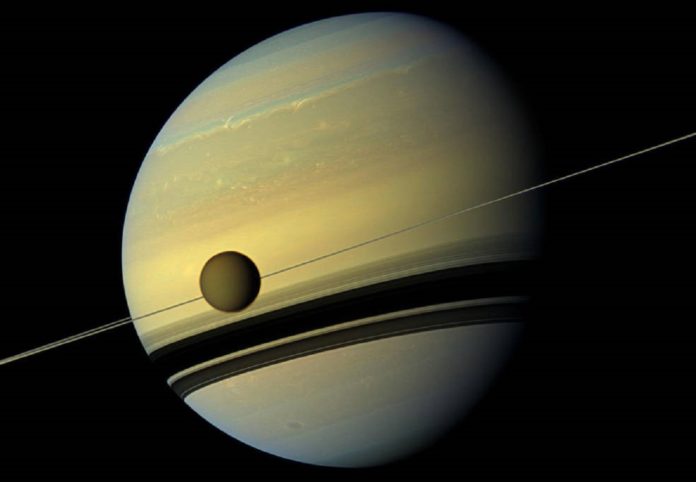

Titan is the largest moon of Saturn and the second-largest natural satellite in the Solar System.

The atmosphere of Titan is largely nitrogen; minor components lead to the formation of methane and ethane clouds and nitrogen-rich organic smog. The climate—including wind and rain—creates surface features similar to those of Earth, such as dunes, rivers, lakes, seas.

Titan orbits Saturn at 20 Saturn radii. But, a new study suggests that Titan’s orbit around Saturn is expanding. Means, the moon is getting farther and farther away from the planet—at a rate about 100 times faster than expected.

According to the study, Titan was born much closer to Saturn. It migrated out to its current distance of 1.2 million kilometers (about 746,000 miles) over 4.5 billion years.

Caltech’s Jim Fuller, assistant professor of theoretical astrophysics and co-author on the new paper, said, “Most prior works had predicted that moons like Titan or Jupiter’s moon Callisto were formed at an orbital distance similar to where we see them now. This implies that the Saturnian moon system, and potentially its rings, have formed and evolved more dynamically than previously believed.”

To better comprehend the basics of orbital migration, consider the example of Earth and Moon. Earth’s moon exerts a small gravitational pull on the planet as it orbits. This is what causes tides: the moon’s rhythmic tugs cause Earth’s oceans to bulge from side to side. This process truly is gradual, though; Earth will not “lose” the moon until both the earth and moon are engulfed by the sun in roughly six billion years.

The same happens to Titan and Saturn. Titan exerts a similar pull on Saturn. But due to Saturn’s gaseous composition, it’s frictional process is quite weaker than Earth.

Some standard theories have predicted that because of its distance from Saturn, Titan should be migrating away at a sluggish rate of at most 0.1 centimeters per year. But the new results contradict this prediction.

For this study, scientists used different techniques to measure Titan’s orbit over a decade. One of the methods called astrometry offered accurate estimations of Titan’s position relative to background stars in images taken by the Cassini spacecraft. On the other hand, another technique called radiometry gauged Cassini’s velocity as it was affected by the gravitational influence of Titan.

From the two different methods of analysis, scientists obtained results that are in full agreement. The results are also in agreement with a theory proposed in 2016 by Fuller, who predicted that Titan’s migration rate would be much faster than standard tidal theories estimated. His approach notes that Titan is expected to gravitationally squeeze Saturn with a particular frequency that makes the planet oscillate strongly, similarly to how swinging your legs on a swing with the right timing can drive you higher and higher.

This procedure of tidal forcing is called resonance locking. Fuller suggested that the high amplitude of Saturn’s oscillation would disperse a lot of energy, which thus would make Titan migrate outward away from the planet at a quicker rate than recently suspected. In reality, both observations found that Titan is migrating away from Saturn at a pace of 11 centimeters for each year, more than 100 times quicker than past hypotheses anticipated.

Fuller said, “The resonance locking theory can apply to many astrophysical systems. I’m now doing some theoretical work to see if the same physics can happen in binary star systems or exoplanet systems.”

Journal Reference:

- Valéry Lainey et al. Resonance locking in giant planets indicated by the rapid orbital expansion of Titan. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-020-1120-5