Large carnivorous dinosaurs known as tyrannosaurids saw significant variations in their body proportions and skull robusticity as they developed. This indicated that they filled distinct ecological niches throughout their lives. The nutrition of young tyrannosaurid dinosaurs is mainly unknown, even though adults frequently consume megaherbivorous dinosaurs.

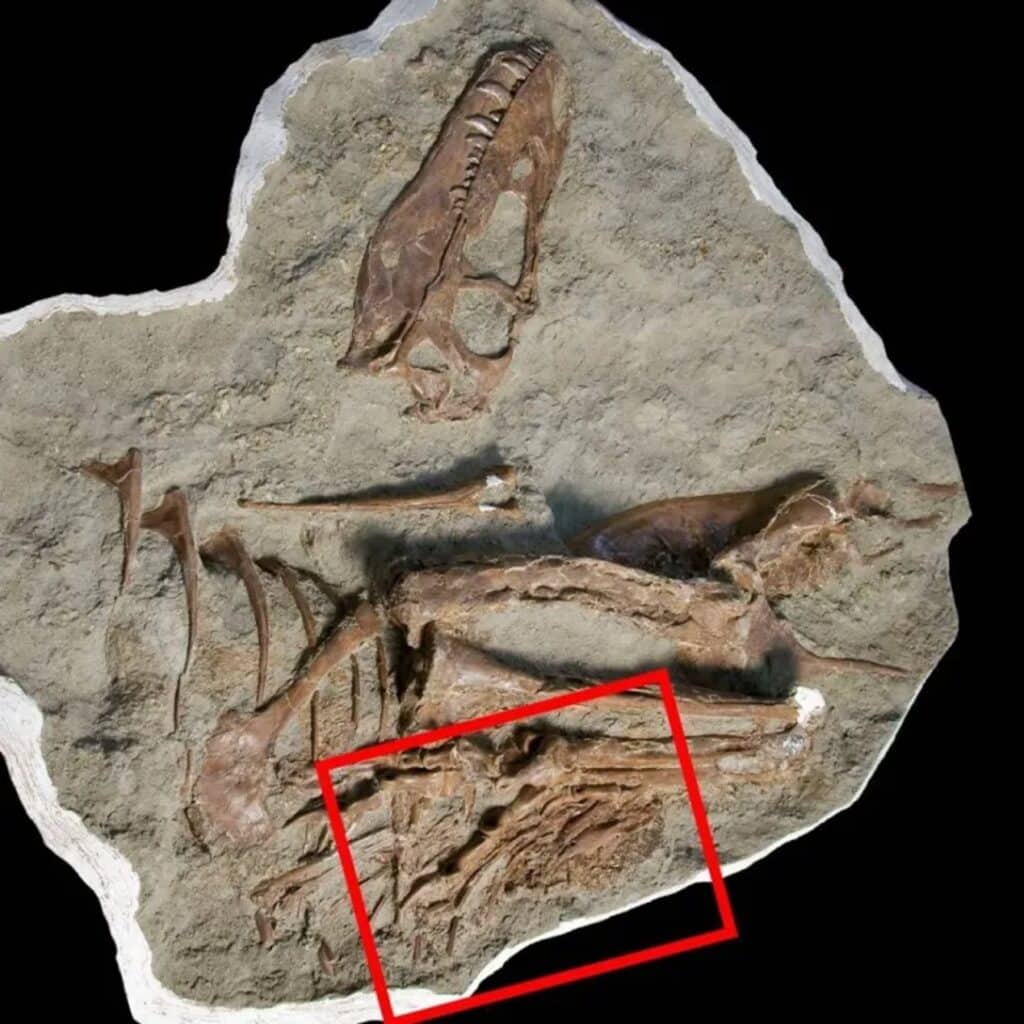

A new study by the Royal Tyrrell Museum offers new insights into the diet of tyrannosaurs based on an extraordinary specimen that contains the last meal of a young meat-eating dinosaur. For the first time, the contents of a fossilized tyrannosaur’s stomach have been discovered intact.

The specimen was initially found in 2009 by Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology staff in Dinosaur Provincial Park.

Living in what is now southern Alberta, Gorgosaurus was a tyrannosaur that existed 75 million years ago—many million years before Tyrannosaurus rex. It has been estimated that the dinosaur died between five and seven years old. Its juvenile weight was probably just 335 kg or 13% of an adult Gorgosaurus’s total body mass.

In the museum lab, scientists found parts of two small dinosaurs inside the belly of a Gorgosaurus. Before it died, the Gorgosaurus had eaten two young, bird-like herbivorous dinosaurs called Citipes elegans. Instead of eating them whole, the young tyrannosaur only ate the back legs, which are the meatier parts of the body. The prey dinosaurs were like Oviraptors from Asia and were called caenagnathids.

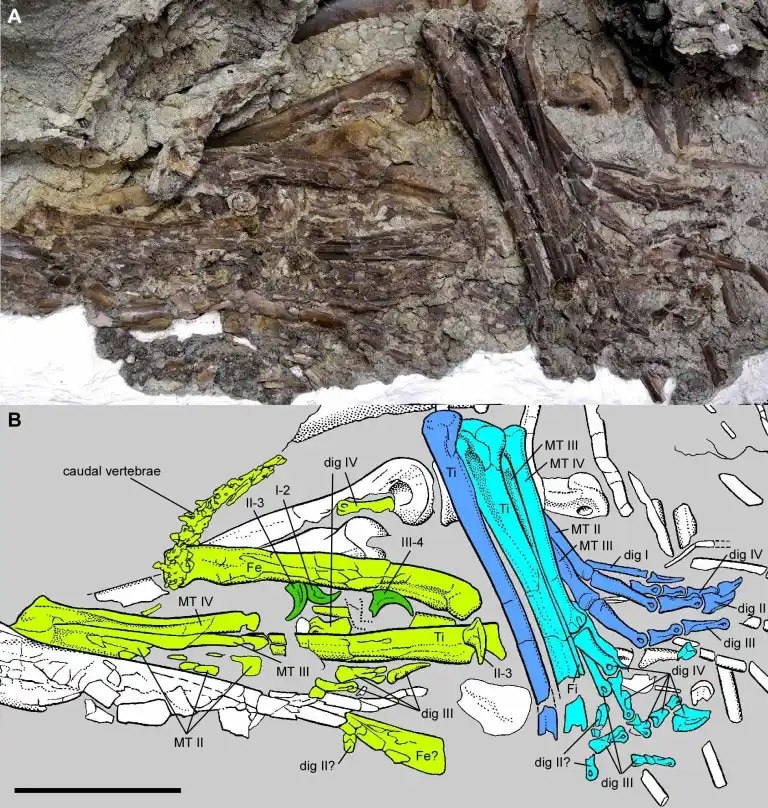

In the illustration, the green color indicates the remains of the first Citipes individual the gorgosaur consumed. Blue shows the fossilized bones from the second Citipes individual.

A detailed examination of the preserved bones reveals that the deaths of both Citipes individuals occurred during their first year of life.

Like contemporary crocodiles, Tyrannosaurs broke down their prey’s bones in their stomachs. Scientists were able to determine that the contents of the gorgosaur’s stomach represented two distinct meals, consumed hours or days apart because the components of the two Citipes individuals were at different stages of digestion. Given that the two dinosaurs in the stomach contents were of the same species and age but were consumed at other dates, it is possible that young caenagnathids were among the juvenile gorgosaurs’ preferred prey.

This discovery is the first to show that young gorgosaurs ate different things than the grown-up ones. As seen from tooth marks on bones, adults hunted big plant-eating dinosaurs like horned and duck-billed ones. They used their large skulls and big teeth to catch and eat these large prey, including biting through bones.

On the other hand, juvenile gorgosaurs were not equipped to hunt enormous prey. They were lean, with narrow skulls, blade-like teeth, and long, slender hind limbs. They were ideally suited for capturing and dismembering small and young prey. These features made them perfect for catching and taking apart small and young animals for their meals.

Scientists noted, “The clues we’ve found suggest that tyrannosaurs took on different roles in their environment as they got older. They probably focused on hunting smaller and younger dinosaurs when they were young. But as they grew up, they likely shifted to targeting larger plant-eating dinosaurs. This change in the diet seems to have started around the age of 11, when their skulls and teeth began to get stronger and more robust. So, it looks like young tyrannosaurs were like specialized hunters for smaller prey, and as they matured, they adapted to take down bigger herbivores.”

Journal Reference:

- Therrien, F., Zelenitsky, D.K., Tanaka, K., Voris, J.T., Erickson, G.M., Currie, P.J., DeBuhr, C.L., Kobayashi, Y. Exceptionally preserved stomach contents of a young tyrannosaurid reveal an ontogenetic dietary shift in an iconic extinct predator. Science Advances. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi0505