Earthquakes send seismic waves through the Earth’s layers at the same speed. The South Pacific Ocean’s Kermadec Islands region experienced a strong earthquake in May 1997. A second large earthquake struck the same site in September 2018, just over 20 years later, with its seismic energy coming from the same area.

In data recorded at four of more than 150 Global Seismographic Network stations that log seismic vibrations in real-time, a new study found an anomaly among the twin events: During the 2018 earthquake, a set of seismic waves known as SKS waves traveled about one second faster than their counterparts had in 1997.

This one-second difference in SKS wave travel time offers a crucial and unprecedented glimpse of what’s going on further inside the Earth’s interior and outer core.

The Earth could not sustain life without its magnetic field, and the magnetic field wouldn’t work without the moving flows of liquid metal in the outer core. However, scientific understanding of this dynamic is based on simulations.

Ying Zhou, a geoscientist with the Department of Geosciences at the Virginia Tech College of Science, said, “We only know that in theory, if you have convection in the outer core, you’ll be able to generate the magnetic field.”

Additionally, scientists have only been able to guess the cause of the gradually observed variations in the magnetic field’s strength and direction, which most likely entail changing flows in the outer core.

Zhou said, “If you look at the north geomagnetic pole, it’s currently moving at a speed of about 50 kilometers [31 miles] per year. It’s moving away from Canada and toward Siberia. The magnetic field is not the same every day. It’s changing. Since it’s changing, we also speculate that convection in the outer core changes with time, but there’s no direct evidence. We’ve never seen it.”

Zhou set out to find that evidence. She said, “The changes happening in the outer core aren’t dramatic, but they’re worth confirming and fundamentally understanding.”

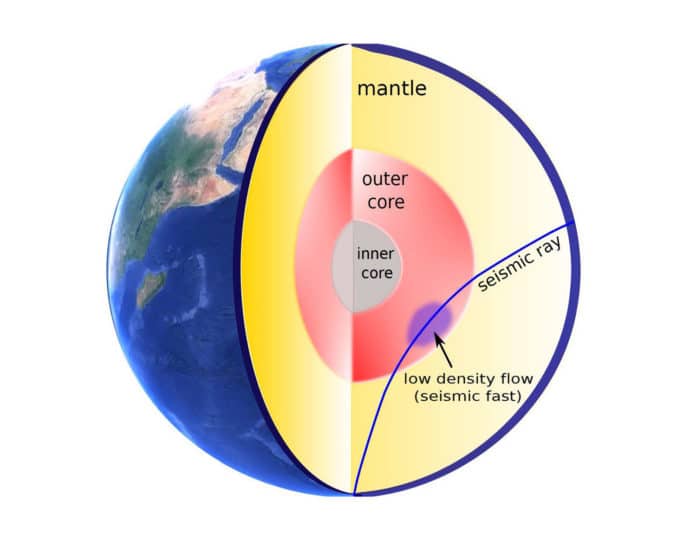

In seismic waves and their changes in speed on a decade time scale, Zhou saw a means for “direct sampling” of the outer core. That’s because the SKS waves she studied pass right through it.

“SKS” represents three phases of the wave:

- It goes through the mantle as an S wave or shear wave.

- Into the outer core as a compressional wave.

- Back out through the mantle as an S wave.

How fast these waves travel depends partly on the density of the outer core in their path. If the thickness is lower in a region of the outer core as the wave penetrates, the wave will travel faster, just as the anomalous SKS waves did in 2018.

Zhou said, “Something has changed along the path of that wave so that it can go faster now.”

“The difference in wave speed points to low-density regions forming in the outer core in the 20 years since the 1997 earthquake. That higher SKS wave speed during the 2018 earthquake can be attributed to the release of light elements such as hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen in the outer core during convection as the Earth cools.”

“The material that was there 20 years ago is no longer there. This is new material, and it’s lighter. These light elements will move upward and change the density in the region where they’re located.”

“It’s evidence that movement is happening in the core, and it’s changing over time, as scientists have theorized. We’re able to see it now. If we can see it from seismic waves, in the future, we could set up seismic stations and monitor that flow.”

Scientists are further planning to analyze continuous seismic recordings from two seismic stations. One of them will act as a “virtual” earthquake source.

Zhou said, “We can use earthquakes, but the limitation of relying on earthquake data is that we can’t control the locations of the earthquakes. But we can control the locations of seismic stations. We can put the stations anywhere we want them to be, with the wave path from one station to the other station going through the outer core. If we monitor that over time, we can see how core-penetrating seismic waves between those two stations change. With that, we will be better able to see fluid movement in the outer core with time.”

Journal Reference:

- Zhou, Y. Transient variation in seismic wave speed points to fast fluid movement in the Earth’s outer core. Commun Earth Environ 3, 97 (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s43247-022-00432-7