The Earth’s crust is what we live on and is by far the thinnest layers of Earth. The thickness varies depending on where you are on Earth, with the oceanic crust being 5-10 km and continental mountain ranges being up to 30-45 km thick.

But what happens below this crust remains obscure, including the fate of sections of crust that vanish back into the Earth.

Now, a team of geochemists based at the Florida State University-headquartered National High Magnetic Field Laboratory has found some significant clues about where those rocks have been hiding.

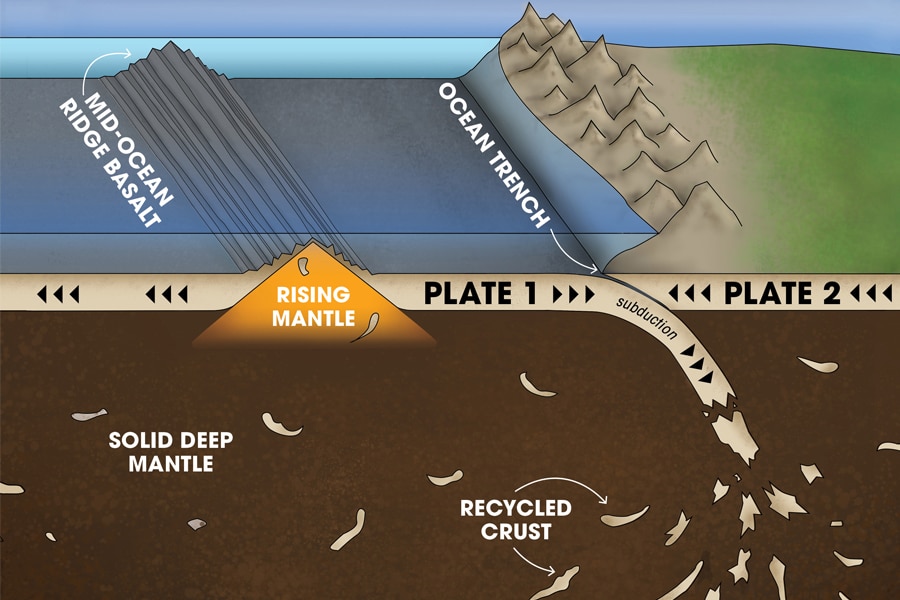

A new study has come out with fresh evidence that while most of the Earth’s crust is relatively new, a small percentage is made up of ancient chunks that had sunk long ago back into the mantle then later resurfaced. They also found that based on the amount of that “recycled” crust, that the planet had been churning out crust consistently since its formation 4.5 billion years ago—a picture that contradicts prevailing theories.

Co-author Munir Humayun, a MagLab geochemist and professor at Florida State’s Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Science (EOAS) said, “Like salmon returning to their spawning grounds, some oceanic crust returns to its breeding ground, the volcanic ridges where the fresh crust is born. We used a new technique to show that this process is essentially a closed-loop and that recycled crust is distributed unevenly along ridges.”

Scientists have long estimated about what happens to subducted crust after being reabsorbed into the hot, high-pressure environment of the planet’s mantle. It may sink further into the mantle and settle there, or ascend back to the surface in tufts, or to the surface in plumes, or swirl through the mantle.

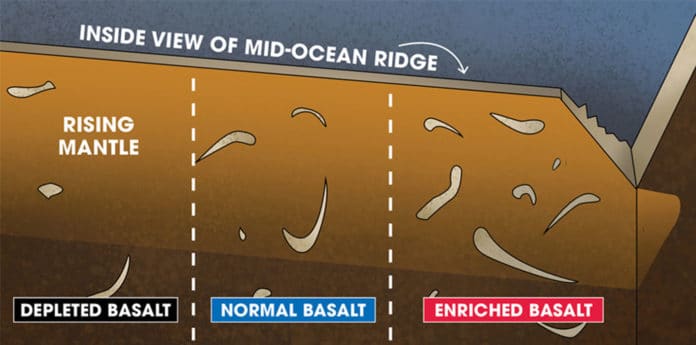

Scientists had already seen clues supporting the theory. Some basalts collected from mid-ocean ridges, called enriched basalts, have a higher percentage of certain elements that tend to seep from the mantle into the melt from which basalt is formed; others, called depleted basalts, had much lower levels.

To highlight the mystery of the disappearing crust, scientists observed 500 samples of basalt collected from 30 regions of ocean ridges. Some were enriched, some were depleted, and some were in between.

Scientists discovered that the overall extents of germanium and silicon were lower in melts of the recycled crust than in the “virgin” basalt rising out of melted mantle rock. So they built up another strategy that pre-owned that proportion to distinguish a particular chemical fingerprint for the subducted crust.

They thus devised an accurate technique to measure the ratio using a mass spectrometer at the MagLab. Then they crunched the numbers to see how these ratios differed among the 30 regions sampled, expecting to see variations that would shed light on their origins.

Scientists first discovered nothing. This concerned scientists, and they started looking at the problem from a wider view. Instead of comparing the basalts of different regions, they compared enriched and depleted basalts.

After quickly re-crunching the data, scientists were thrilled to see apparent differences among those groups of basalts.

The team had detected lower germanium-to-silicon ratios in enriched basalts—the chemical fingerprint for the recycled crust—across all the regions they sampled, pointing to its marble cake-like spread throughout the mantle. Essentially, they solved the mystery of the vanishing crust.

Humayun said, “Sometimes you’re looking too closely, with your nose in the data, and you can’t see the patterns. Then you step back, and you go, ‘Whoa!'”

Digging deeper into the patterns they found, the scientists unearthed more secrets. Based on the amounts of enriched basalts detected on global mid-ocean ridges, the team was able to calculate that about 5 to 6 percent of the Earth’s mantle is made of recycled crust. This figure sheds new light on the planet’s history as a crust factory. Scientists had known the Earth cranks out crust at the rate of a few inches a year. But has it done so consistently throughout its entire history?

Their analysis, Humayun said, indicates that “The rates of crust formation can’t have been radically different from what they are today, which is not what anybody expected.”

Journal Reference:

- Elemental constraints on the amount of recycled crust in the generation of mid-oceanic ridge basalts (MORBs)” Science Advances (2020). DOI: /10.1126/sciadv.aba2923