Mammals, birds, and squamates (lizards, snakes, and relatives) are key living vertebrates, and thus understanding their evolution underpins important questions in biodiversity science. Whereas the origins of mammals and birds are relatively well understood, the roots of squamates have been obscure.

A new study by the University of Bristol reports a modern-type lizard from the Late Triassic of England. They retrieved the specimen of the lizard from a cupboard of the Natural History Museum in London. The analysis showed that modern lizards originated in the Late Triassic and not the Middle Jurassic, as previously thought.

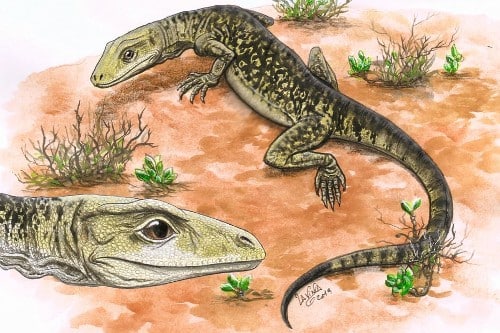

The team has named their incredible discovery Cryptovaranoides microlanius, meaning ‘small butcher’ in tribute to its jaws filled with sharp-edged slicing teeth.

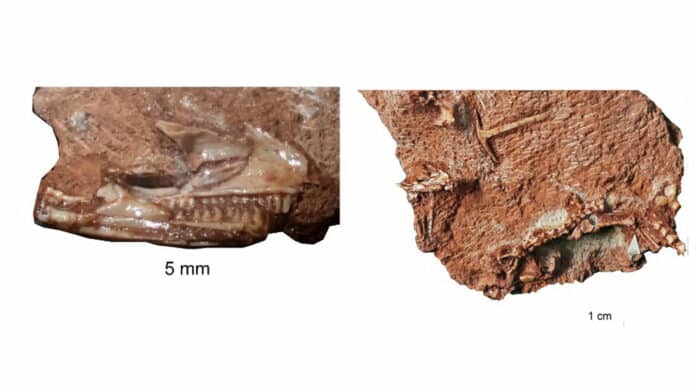

Dr. David Whiteside of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences said, “I first spotted the specimen in a cupboard full of Clevosaurus fossils in the storerooms of the Natural History Museum in London, where I am a Scientific Associate. This was a common enough fossil reptile, a close relative of the New Zealand Tuatara that is the only survivor of the group, the Rhynchocephalia, that split from the squamates over 240 million years ago.”

“Our specimen was simply labeled ‘Clevosaurus and one other reptile.’ As we continued to investigate the specimen, we became more and more convinced that it was more closely related to modern-day lizards than the Tuatara group.”

“We made X-ray scans of the fossils at the University, and this enabled us to reconstruct the fossil in three dimensions and see all the tiny bones hidden inside the rock.”

Cryptovaranoides is a squamate because it differs from Rhynchocephalia in the braincase, the neck vertebrae, the shoulder area, the presence of a median, upper tooth in the front of the mouth, the way the teeth are set in the jaws (rather than being fused to the crest of the jaws), and the skull architecture, such as the absence of a lower temporal bar. There is only one significant primordial characteristic that cannot be found in contemporary squamates, and that is an opening where an artery and nerve pass through on one side of the upper arm bone’s humerus.

Although experts have noted that many snakes, including Boas and Pythons, have many rows of huge teeth in the same region, Cryptovaranoides does exhibit a few other seemingly primitive characteristics, such as a few rows of teeth on the bones of the roof of the mouth. Despite this, it has a sophisticated braincase like most live lizards do, and the connections between the bones in its skull imply that it is flexible.

Co-author Professor Mike Bento said, “In terms of significance, our fossil shifts the origin and diversification of squamates back from the Middle Jurassic to the Late Triassic. This was a time of major restructuring of ecosystems on land, with origins of new plant groups, especially modern-type conifers, new kinds of insects, and some of the first modern groups such as turtles, crocodilians, dinosaurs, and mammals.”

“Adding the oldest modern squamates then completes the picture. It seems these new plants and animals came on the scene as part of a major rebuilding of life on Earth after the end-Permian mass extinction 252 million years ago, and especially the Carnian Pluvial Episode 232 million years ago when climates fluctuated between wet and dry and caused great perturbation to life.”

Ph.D. research student Sofia Chambi-Trowell commented: “The name of the new animal, Cryptovaranoides microlanius, reflects the hidden nature of the beast in a drawer but also in its likely lifestyle, living in cracks in the limestone on small islands that existed around Bristol at the time. The species name, meaning ‘small butcher,’ refers to its jaws filled with sharp-edged slicing teeth, and it would have preyed on arthropods and small vertebrates.”

Dr. Whiteside concluded: “This is a very special fossil and likely to become one of the most important found in the last few decades. It is fortunate to be held in a National Collection, in this case, the Natural History Museum, London. We would like to thank the late Pamela L. Robinson, who recovered the fossils from the quarry and did a lot of preparation work on the type specimen and associated bones. It was a pity she did not have access to CT scanning technology to help her observe all the detail of the specimen.”

Journal Reference:

- David I. Whiteside et al. A Triassic crown squamate. Science Advances. 2 Dec 2022. Vol 8, Issue 48. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq8274