During the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition, there was a significant increase in animal diversity and different burrowing strategies. This coincided with the exploration of new ecological spaces and the colonization of the water column. The reasons behind this evolutionary surge are debated, but many believe that the convergent evolution of predation and subsequent arms races played a crucial role.

A recent study unveils the discovery of fossils belonging to a new group of animal predators in the Early Cambrian Sirius Passet fossil site in North Greenland. These sizable worms might be among the earliest carnivorous animals to inhabit the water column over 518 million years ago, unveiling a previously unknown lineage of predators.

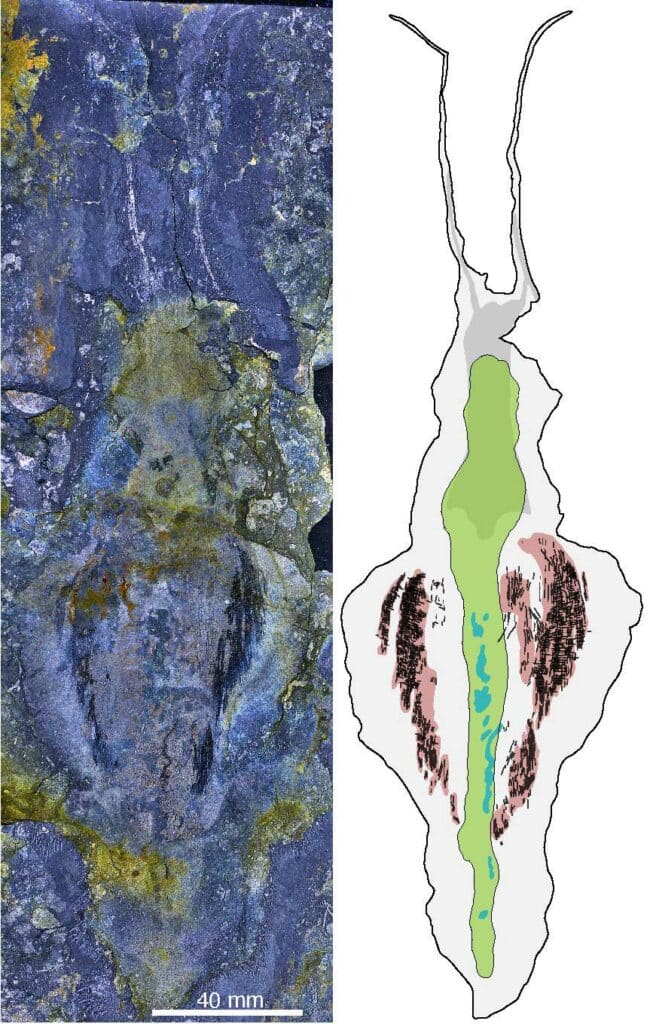

The newly identified fossils are named Timorebestia, meaning ‘terror beasts’ in Latin.

Timorebestia is a distant but close relative of living arrow worms, or chaetognaths. Chaetognaths, with their characteristic grasping spines, are the oldest known pelagic predators in the lowest Cambrian (Terreneuvian).

Dr Jakob Vinther, a senior author from the University of Bristol‘s Schools of Earth Sciences, said, “Our research shows that these ancient ocean ecosystems were fairly complex with a food chain that allowed for several tiers of predators.”

Inside the fossilized digestive system of Timorebestia, researchers discovered remnants of a prevalent swimming arthropod known as Isoxys. The findings indicate that Isoxys served as a common food source for many animals in the Sirius Passet region. Despite having long protective spines pointing both forwards and backward, these arthropods were not entirely successful in avoiding predation, as Timorebestia was observed consuming them in substantial quantities.

Arrow worms are one of the oldest animal fossils from the Cambrian period. Despite arthropods appearing in the fossil record about 521 to 529 million years ago, arrow worms have an even earlier presence, dating back at least 538 million years.

Both arrow worms and the more primitive Timorebestia were swimming predators. This suggests that they likely dominated the oceans as predators before the rise of arthropods. This ancient dynasty may have spanned approximately 10-15 million years before being surpassed by other, more successful groups.

Luke Parry from Oxford University, who was part of the study, added, “Timorebestia is a significant find for understanding where these jawed predators came from.”

“Today, arrow worms have menacing bristles on the outside of their heads for catching prey, whereas Timorebestia has jaws inside its head.”

“This is what we see in microscopic jaw worms today—organisms that arrow worms shared an ancestor with over half a billion years ago. Timorebestia and other fossils like it link closely related organisms that look very different today.”

Tae Yoon Park from the Korean Polar Research Institute, senior author and field expedition leader said, “Our discovery firms up how arrow worms evolved. Living arrow worms have a distinct nervous center on their belly called a ventral ganglion. It is unique to these animals.”

“We have found this preserved in Timorebestia and another fossil called Amiskwia. People have debated whether or not Amiskwia was closely related to arrow worms as part of their evolutionary stem lineage. The preservation of these unique ventral ganglia gives us a great deal more confidence in this hypothesis.”

“We are very excited to have discovered such unique predators in Sirius Passet. Over a series of expeditions to the very remote Sirius Passet in the furthest reaches of North Greenland, more than 82,5˚ north, we have collected a great diversity of exciting new organisms. Thanks to the remarkable, exceptional preservation in Sirius Passet, we can also reveal exciting anatomical details, including their digestive system, muscle anatomy, and nervous systems.”

“We have many more exciting findings to share in the coming years that will help show how the earliest animal ecosystems looked like and evolved.”

Journal Reference:

- Tae-Yoon Park, Jakob Vinther et al. A giant stem-group chaetognath. Science Advances. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi6678