Permian extinction, also called Permian-Triassic extinction or end-Permian extinction, is the largest extinction in Earth’s history, some 252 million years ago. The extinction reset the evolution of life.

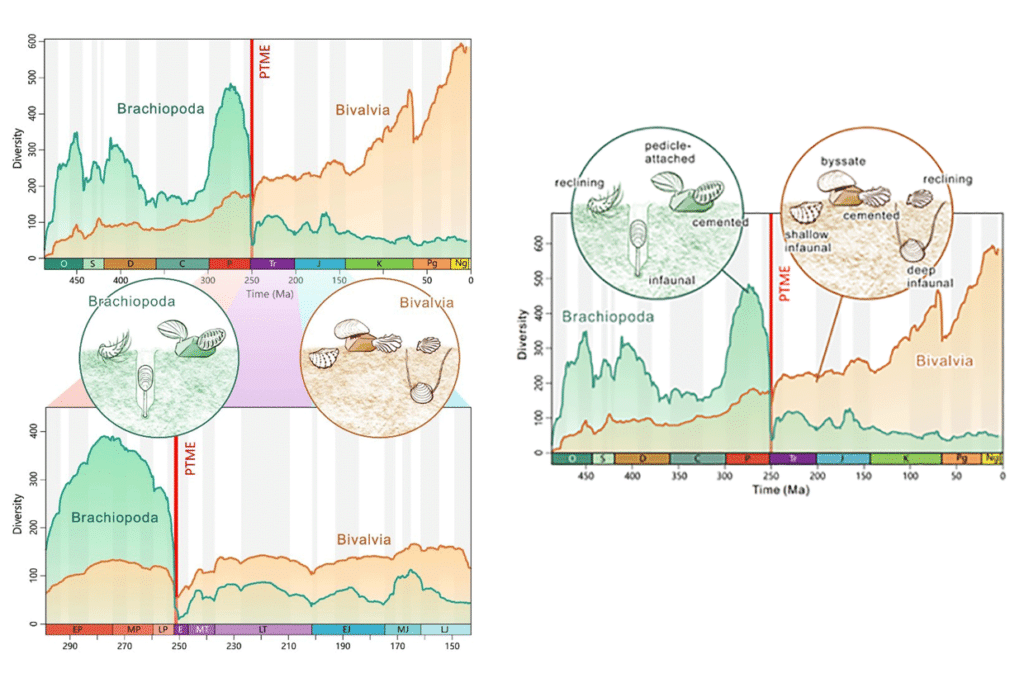

Brachiopods, sometimes called “lamp shells,” were replaced ecologically by bivalves, such as oysters and clams, during one of the largest events in Earth‘s history. This resulted from the devastating end-Permian mass extinction, suggested a new study by paleontologists based in Bristol, UK, and Wuhan, China.

Their study shed new light on this crucial transition when ocean ecosystems changed from ancient to modern styles.

Both land and marine life are abundant and contribute to specific ecosystems. Bivalves, gastropods, corals, crustaceans, and fish are among the species that dominate the seafloor in current oceans. However, all of these ecosystems go back to the Triassic, when life started to recover from the brink. Only one out of every twenty species survived the crisis, and there has been much discussion about how the new ecosystems were built and why certain groups survived while others did not.

Before the extinction, brachiopods dominated shelled animals; however, bivalves survived because they could better adapt to their new environment.

Zhen Guo at Wuhan and Bristol, who led the project, said, “A classic case has been the replacement of brachiopods by bivalves. Paleontologists used to say that the bivalves were better competitors and so beat the brachiopods somehow during this crisis time. There is no doubt that brachiopods were the major group of shelled animals before the extinction, and bivalves took over after.”

In particular, the researchers were interested in learning more about interactions between brachiopods and bivalves during the Permian-Triassic transitional period. To determine rates of origination, extinction, and fossil preservation and whether brachiopods and bivalves interacted with one another, scientists opted to apply a computational technique known as Bayesian analysis. For instance, did the emergence of bivalves contribute to the extinction of brachiopods?

Professor Michael Benton from Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences said, “We found that both groups shared similar trends in diversification dynamics right through the crisis time.”

This indicates that they were more likely to respond to comparable external causes, such as sea temperature and transient crises, than they were competing or preying on one another. But finally, the bivalves won out, and the brachiopods withdrew to deeper waters, where they still exist, albeit in smaller numbers.

Professor Zhong-Qiang Chen of Wuhan commented: “It was great to see how modern computational methods can tackle such a long-standing question.”

“We always thought that the end-Permian mass extinction marked the end of the brachiopods, and that was that. But it seems that both brachiopods and bivalves were hit hard by the crisis, and both recovered in the Triassic, but the bivalves could adapt better to high ocean temperatures. So, this gave them the edge, and after the Jurassic, they just rocketed in numbers, and the brachiopods didn’t do much.”

Zhen Guo said: “I had to check and compile records of over 330000 fossils of brachiopods and bivalves through the study interval, and then run the Bayesian analysis, which took weeks and weeks on the Bristol supercomputer. I like the method, though, because it repeats everything millions of times to take account of all kinds of uncertainties in the data and gives a great deal of rich information about what was going on.”

The study supports the idea that extinction events and environmental stressors, rather than competition, shaped the distinct fates of brachiopods and bivalves over macroevolutionary periods.

Journal Reference:

- Guo, Z., Flannery-Sutherland, J.T., Benton, M.J. et al. Bayesian analyses indicate bivalves did not drive the downfall of brachiopods following the Permian-Triassic mass extinction. Nat Commun 14, 5566 (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-41358-8