A new study offers evidence that doing exercise can help prevent the most common type of liver cancer hepatocellular carcinoma. Through this study, scientists also identified the molecular signaling pathways involved in this process.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer that occurs most often in people with chronic liver diseases, such as cirrhosis caused by hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection.

More than 800,000 people worldwide are diagnosed with this cancer each year.

Yet, there are very few effective therapies available for this cancer. Thus, new approaches are required.

Lead investigator Geoffrey C. Farrell, MD, Liver Research Group, ANU Medical School, Australian National University at The Canberra Hospital, Garran, ACT, Australia explained, “Some population data suggest that persons who exercise regularly are less likely to develop liver cancer but, studies addressing whether this has a real biological basis, and, if so, identifying the molecular mechanism that produces such a protective effect, are few and the findings have been inconclusive.”

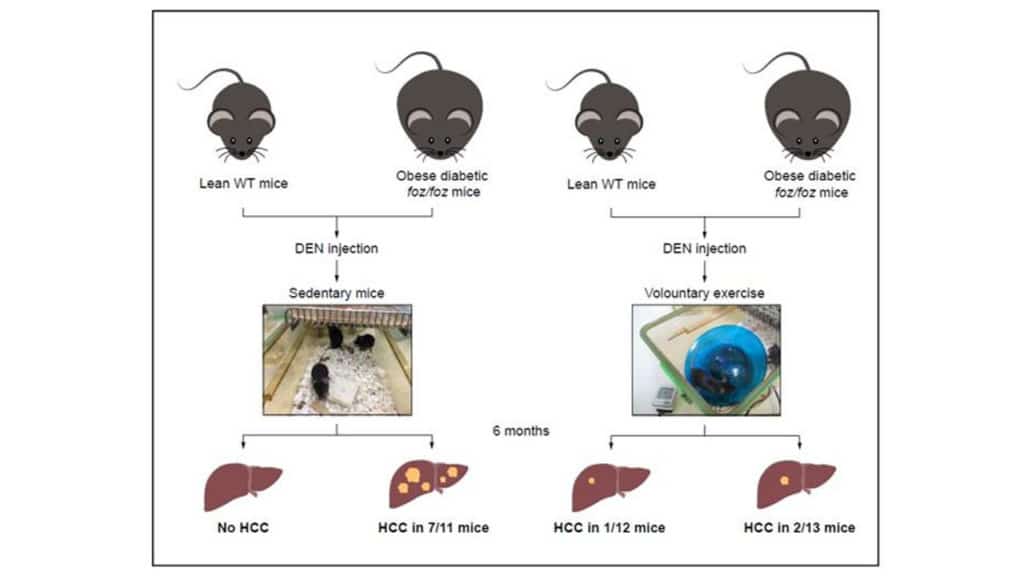

Scientists conducted their study on obese/diabetic mice. They tested whether exercise reduces the development of liver cancer in mice.

For this, mice genetically are driven to eat so that they become obese and develop type 2 diabetes as young adults were injected early in life with a low dose of a cancer-causing agent. Half of the mice were allowed regular access to a running wheel; the other half were not and remained sedentary.

The mice ran up to 40 kilometers a day as measured by rotations of the exercise wheel. This slowed down the weight gain for three months, but at the end of six months of experiments, even the exercising mice were obese. At six months, most of the sedentary mice had liver cancer, while none of the exercising mice had developed it.

Based on the trails, scientists concluded that exercise could stop the development of liver cancer in mice. In particular, while about every single obese mouse infused with a low dose of malignant growth, causing agents to develop liver cancer within six months, mice that regularly exercised failed to do so. They were completely protected against liver cancer development in the timeframe of these experiments. Weight control did not mitigate the development of liver cancer.

In this study, scientists found that the beneficial effects of voluntary exercise were exerted via molecular signaling pathways, two of which were identified as tumor suppressor gene p53 and the stress-activated protein kinase JNK1.

Scientists found that exercise can switch off the ley factor JNK1. They also demonstrated that activated p53, known as “guardian of the cell,” is essential for the regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor, p27, thereby stopping the persistent growth of altered cells destined to become cancerous.

Journal Reference:

- Exercise retards hepatocarcinogenesis in obese mice independently of weight control. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.02.006