Explosive volcanism is a major cause of climate variability. It is necessary to have accurate event chronologies and projections of the burden and altitude of volcanic sulfate aerosol to comprehend the long-range societal effects of eruption-forced climatic shifts.

Medieval monks unintentionally documented some of history’s most significant volcanic eruptions by watching the night sky.

An international team of researchers led by the University of Geneva (UNIGE) used readings from 12th and 13th-century European and Middle Eastern chronicles, as well as ice core and tree ring data, to precisely date some of the world’s largest volcanic eruptions.

Their findings, published in the journal Nature, provide new insight into one of the most volcanically active times in Earth’s history, which some belief contributed to the onset of the Little Ice Age.

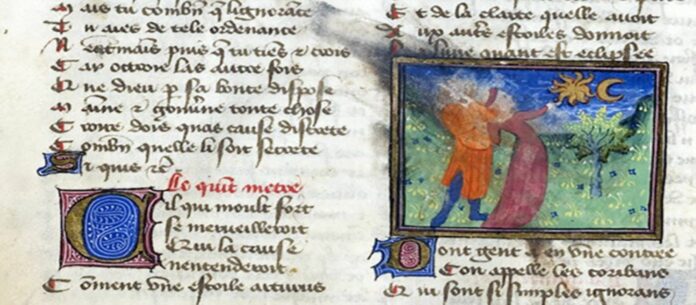

The researchers searched hundreds of annals and chronicle from Europe and the Middle East for references to total lunar eclipses and their coloration. Total lunar eclipses occur when the Moon moves directly into the shadow of the Earth. Because the Moon is still bathed in sunlight and twisted around the Earth by its atmosphere, it is usually visible as a reddish orb. However, after a large volcanic eruption, there can be so much dust in the stratosphere that the eclipsed moon almost vanishes.

The actions of kings and popes, as well as major battles, natural disasters, and famines, were documented and described by medieval chroniclers.

The celestial phenomena that could foretell such disasters were equally notable. The monks were particularly attentive to the Moon’s coloration, recalling the Book of Revelation, a vision of the end times that speaks of a blood-red moon.

They discovered that the chroniclers had faithfully documented 51 of the 64 lunar eclipses in Europe between 1100 and 1300. Five of these reports also stated that the Moon was unusually black.

The study’s lead author, Sébastien Guillet, senior research associate at the UNIGE Institute for environmental sciences, said, “I was listening to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon album when I realized that the darkest lunar eclipses all occurred within a year or so of major volcanic eruptions. Because we know the precise dates of the eclipses, we can use the sightings to narrow down when the eruptions must have occurred.”

The researchers discovered that Japanese scribes made a note of lunar eclipses, with Fujiwara no Teika writing about an unprecedented dark eclipse witnessed on December 2, 1229.’ The older people had never seen it like this before, with the location of the Moon’s disc not visible, as if it had vanished during the eclipse. It was genuinely something to be afraid of.’

The stratospheric dust from big volcanic eruptions caused the Moon to disappear and cooled summer temps, and destroyed crops.

Markus Stoffel, full professor at the Institute for environmental sciences at the UNIGE and last author of the study, a specialist in converting measurements of tree rings into climate data, who co-designed the study, said, “We know from previous work that strong tropical eruptions can induce global cooling on the order of roughly one °C over a few years. They can also lead to rainfall anomalies with droughts in one place and floods in another.”

Despite these impacts, people did not believe that the poor harvests or unusual lunar eclipses had anything to do with volcanoes at the time.

Co-author Clive Oppenheimer, professor at the Department of Geography at the University of Cambridge, said, “We only knew about these eruptions because they left traces in the ice of Antarctica and Greenland. By putting together the information from ice cores and the descriptions from medieval texts, we can better estimate when and where some of the biggest eruptions of this period occurred.”

Sébastien Guillet worked with climate modelers to determine the most likely timing of the eruptions to make the most of this integration.

He said, “Knowing the season when the volcanoes erupted is essential, as it influences the spread of the volcanic dust and the cooling and other climate anomalies associated with these eruptions.”

Clive Oppenheimer, a professor at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Geography, and Sébastien Guillet, a climate modeler, had combined information from ice cores and medieval texts to improve estimates of when and where some of the Middle Ages’ largest eruptions happened.

The era from 1100 to 1300 is known to be one of the most volcanically active periods in history, with an eruption in the mid-13th century rivaling the famous Tambora eruption of 1815, which caused ‘the year without a summer’ of 1816.

The combined impact of medieval eruptions on Earth’s climate may have resulted in the Little Ice Age when winter ice fairs were held on Europe’s frozen rivers.

The researcher concludes that Improving our grasp of past volcanism’s effects on climate and society during the Middle Ages is critical.

Journal Reference:

- Guillet, S., Corona, etal. Lunar eclipses illuminate the timing and climate impact of medieval volcanism. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05751-z