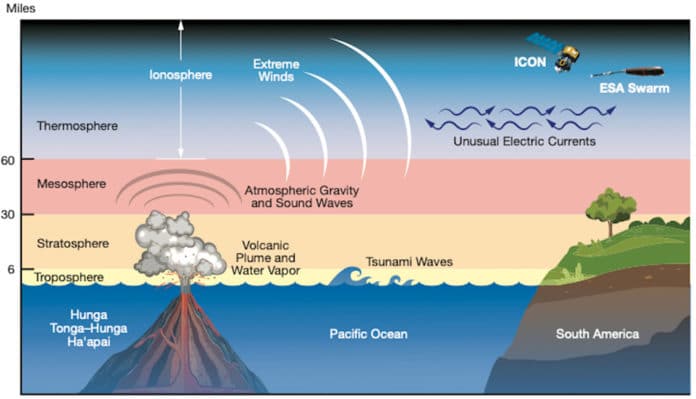

After staying relatively inactive since 2014, the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai volcano erupted on Jan. 15, 2022. It began erupting in late December 2021 and then violently exploded in mid-January 2022. The eruption sent atmospheric shock waves, sonic booms, and tsunami waves worldwide.

Hours after the eruption, the volcano’s effects were found to reach space. The data from NASA’s Ionospheric Connection Explorer, or ICON, mission and ESA’s (the European Space Agency) Swarm satellites suggest that the eruption generated hurricane-speed winds and unusual electric currents in the ionosphere.

Brian Harding, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, and lead author on a new paper discussing the findings, said, “The volcano created one of the largest disturbances in space we’ve seen in the modern era. It allows us to test the poorly understood connection between the lower atmosphere and space.”

Jim Spann, space weather lead for NASA’s Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C, said, “These results are an exciting look at how events on Earth can affect whether in space, in addition to space weather affecting Earth. Understanding space weather holistically will ultimately help us mitigate its effects on society.”

The volcanic eruption lasted for 11 hours. The eruption pushed a giant plume of gases, water vapor, and dust into the sky—the large pressure disturbances generated by the explosion cause fast-moving strong winds that expand into thinner atmospheric layers. ICON detected wind speeds of up to 450 mph as it approached the ionosphere and the edge of space, making them the mission’s strongest winds below 120 miles altitude since launch.

Credits: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens using GOES imagery courtesy of NOAA and NESDIS

The strong winds also influenced electric currents in the ionosphere. The equatorial electrojet is an east-flowing electric current formed by particles in the ionosphere powered by winds in the lower atmosphere. After the eruption, the equatorial electrojet surged to five times its normal peak power and dramatically flipped direction, flowing westward for a short period.

Joanne Wu, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, and co-author of the new study, said, “It’s very surprising to see the electrojet be greatly reversed by something that happened on Earth’s surface. This is something we’ve only previously seen with strong geomagnetic storms, which are a form of weather in space caused by particles and radiation from the Sun.”

The study offers insights into how the events from ground and space affect the ionosphere.

Journal Reference:

- Brian J. Harding, Yen-Jung Joanne Wu et al. Impacts of the January 2022 Tonga Volcanic Eruption on the Ionospheric Dynamo: ICON-MIGHTY and Swarm Observations of Extreme Neutral Winds and Currents. DOI: 10.1029/2022GL098577