A newly digitized vintage film of Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica revealed that ice shelf on the glacier is melting faster than previously thought. The film shows that the glacier is being thawed by a warming ocean more quickly than previously thought.

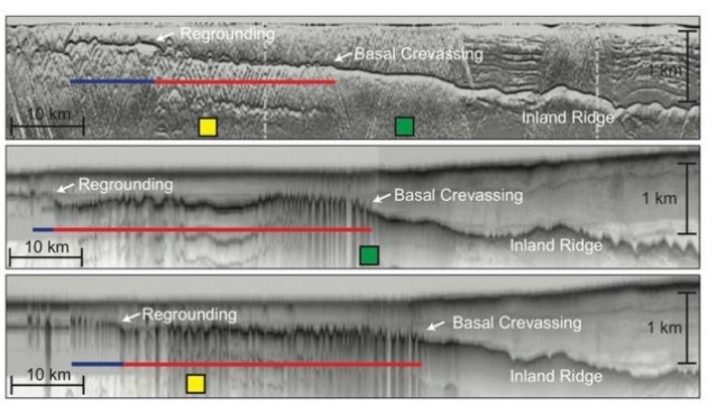

Film from the 1970s has been combined with modern data to appraise that piece of Thwaites Glacier diminished somewhere in the range of 10 and 33 percent somewhere in the range of 1978 and 2009. By expanding the record of changes at the base of glaciers and ice shelves in Antarctica, specialists can likewise better comprehend the procedures that are causing melting, and all the more precisely foresee future ocean level changes.

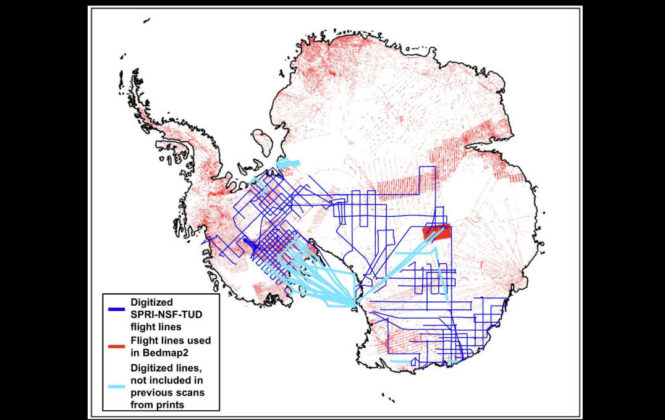

Scientists digitized over 400,000 flight kilometers of Antarctic radar data originally captured on 35mm optical film between 1971 and 1979 by scientists during research flights over the continent. The film was initially recorded in an exploratory survey utilizing ice-penetrating radar. The radar demonstrates mountains, volcanoes, and lakes underneath the frigid surface of Antarctica.

Co-author Professor Martin Siegert, from the Grantham Institute at Imperial, said, “In the 1970s around half of the Antarctic ice sheet was explored systematically using airborne surveys. These first measurements of ice thickness have significant value over 40 years later as they allow ice-sheet change observed in the last decade to be placed in a multi-decadal context.”

Lead author Dr Dustin Schroeder, from Stanford University’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, said: “By having this record, we can now see these areas where the ice shelf is getting thinnest and could breakthrough. This is a pretty hard-to-get-to area and we’re really lucky that they happened to fly across this ice shelf.”

He added: “You can really see the geometry over this long period of time, how these ocean currents have melted the ice shelf – not just in general, but exactly where and how. When we model ice sheet behavior and sea-level projections into the future, we need to understand the processes at the base of the ice sheet that made the changes we’re seeing.”

The data has been released to an online public archive through Stanford Libraries, enabling other scientists to compare it with modern radar data in order to understand long-term changes in ice thickness, features within glaciers and baseline conditions over 40 years.

The team, led by Stanford University and the Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) at Cambridge University, and including an Imperial College London researcher, published their findings today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.