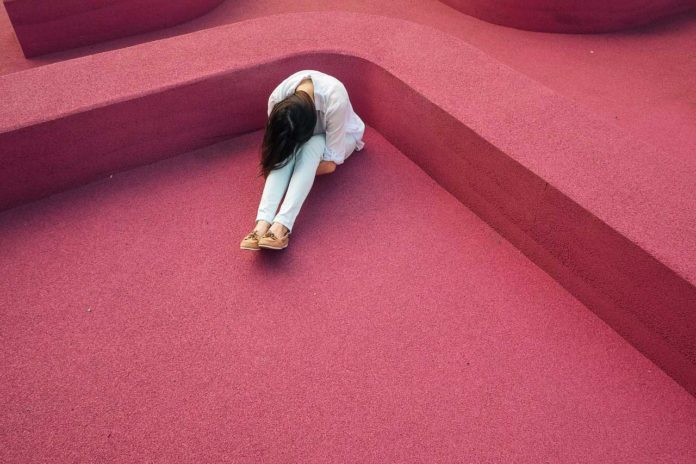

Depression is the primary source of disability worldwide and is relied upon to be the most noteworthy global burden of disease by 2030. In spite of efforts to improve interventions, prevalence is as yet expanding, particularly in adolescence. Evidence recommends that depression during adolescence is related to many concurrent and later mental and social disabilities.

However, what is driving this increase in adolescent depression remains unclear.

Using detailed mood and feeling questionnaires and genetic data from 3,325 teenagers who are a piece of Bristol’s Children of the 90s study, alongside evidence of these risk factors at nine in time they found that childhood bullying was firmly connected with directions of depression that ascent at an early age.

Children who continued to show high depression into adulthood were also more likely to have genetic liability for depression and a mother with postnatal depression. Be that as it may, Children who were harassed; however, did not have any genetic liability for depression showed much lower depressive symptoms as they become young adults.

University of Bristol Ph.D. student Alex Kwong commented:

“Although we know that depression can strike first during the teenage years, we didn’t know how risk factors influenced change over time. Thanks to the Children of the 90s study, we were able to examine at multiple time points the relationships between the strongest risk factors such as bullying and maternal depression, as well as factors such as genetic liability.”

“It’s important that we know if some children are more at risk of depression long after any childhood bullying has occurred. Our study found that young adults who were bullied as children were eight times more likely to experience depression that was limited to childhood. However, some children who were bullied showed greater patterns of depression that continued into adulthood, and this group of children also showed genetic liability and family risk.”

“However, just because an individual has genetic liability to depression does not mean they are destined to go on and have depression. There are several complex pathways that we still don’t fully understand and need to investigate further.”

“The next steps should continue to look at both genetic and environmental risk factors to help untangle this complex relationship that would eventually help influence prevention and coping strategies for our health and education services.”

Lecturer in Psychiatric Epidemiology at the University of Bristol Dr. Rebecca Pearson added:

“The results can help us to identify which groups of children are most likely to suffer ongoing symptoms of depression into adulthood and which children will recover across adolescence. For example, the results suggest that children with multiple risk factors (including family history and bullying) should be targeted for early intervention but that when risk factors such as bullying occur insolation, symptoms of depression may be less likely to persist.”

The study is published in the JAMA Open Network.