One of the obstacles to making enduring, versatile, and agile robots is dealing with the robots’ internal temperature. If the high-torque density motors and exothermic engines that power a robot overheat, the robot will cease to work.

This is a specific issue for soft robots, which are made of engineered materials. While increasingly adaptable, they hold their heat, in contrast to metals, which disseminate heat rapidly. An internal cooling technology, for example, a fan, may not be a lot of help since it would occupy space inside the robot and add weight.

By getting inspired by the natural cooling system that exists in mammals: sweating, scientists from Cornell have created a soft robot muscle that can regulate its temperature through sweating.

Co-lead author T.J. Wallin, M.S. ’16, Ph.D. ’18, a research scientist at Facebook Reality Labs, “Sweating takes advantage of evaporated water loss to dissipate heat rapidly and can cool below the ambient environmental temperature. So as is often the case, biology provided an excellent guide for us as engineers.”

Rob Shepherd, associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, who led the project said, “This form of thermal management is a basic building block for enabling untethered, high-powered robots to operate for long periods of time without overheating.”

In collaboration with the lab of Emmanuel Giannelis, the Walter R. Read Professor of Engineering, scientists created essential nanopolymer materials for sweating using a 3D-printing method, stereolithography, which uses light to cure resin into predesigned shapes. The combination of nanoparticles and polymeric materials enabled scientists to control the viscosity or flow of these fluids.

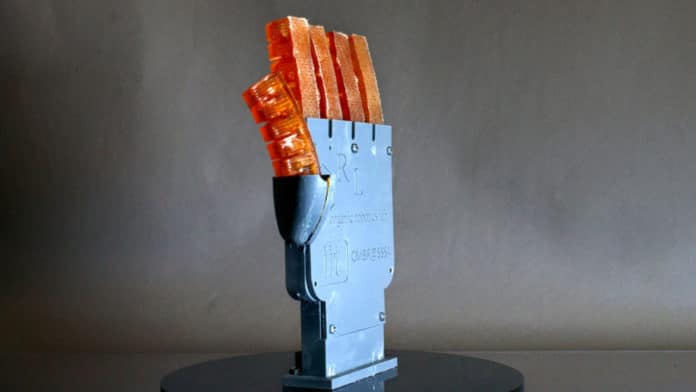

Scientists also invented fingerlike actuators composed of two hydrogel materials that can retain water and respond to temperature – in effect, “smart” sponges.

The base layer, made of poly-N-isopropyl acrylamide, responds to temperatures over 30 C (86 F) by shrinking, which squeezes water up into a top layer of polyacrylamide that is perforated with micron-sized pores. These pores are sensitive to a similar temperature extend and automatically enlarge to release the “sweat,” at that point close when the temperature dips under 30 C.

The evaporation of this water reduces the actuator’s surface temperature by 21 C inside 30 seconds, a cooling procedure that is roughly multiple times more effective than in humans. The actuators can cool around six times faster when presented to wind from a fan.

Co-lead author T.J. Wallin, M.S. ’16, Ph.D. ’18 said, “The best part of this synthetic strategy is that the thermal regulatory performance is based in the material itself. We did not need to have sensors or other components to control the sweating rate. When the local temperature rose above the transition, the pores would simply open and close on their own.”

Shepherd said, “The team incorporated the actuator fingers into a robot hand that could grab and lift objects, and they realized that autonomous sweating not only cooled the hand but lowered the temperature of the object as well. While the lubrication could make a robot hand slippery, that modifications to the hydrogel texture could compensate by improving the hand’s grip, much like wrinkles in the skin.”

“The ability of a robot to secrete fluids could also lead to methods for absorbing nutrients, catalyzing reactions, removing contaminants and coating the robot’s surface with a protective layer.”

Other contributors included postdoctoral associate and co-lead author Anand Mishra; postdoctoral associate Wenyang Pan; doctoral student Patricia Xu; and Barbara Mazzolai of the Italian Institute of Technology’s Center for Micro-BioRobotics.

The team’s paper, “Autonomic Perspiration in 3D Printed Hydrogel Actuators,” published Jan. 29 in Science Robotics.