An international team of scientists, led by the University of Cambridge, has- for the first time- found the cause of Alzheimer’s disease progression in the brain. They found that the disease develops in a very different way than previously thought.

Previously, it was believed that the disease starts from a single point in the brain. It then initiates a chain reaction which leads to the death of brain cells. But, using human data, scientists identified that Alzheimer’s disease reaches different regions of the brain early instead of starting from a single point.

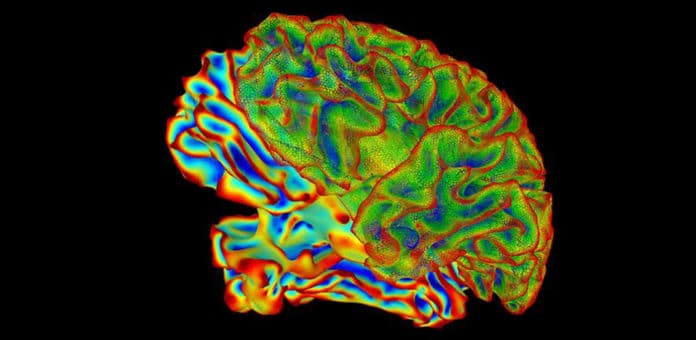

This neurodegenerative disease is thought to be caused by the abnormal build-up of proteins called tau and amyloid-beta. These proteins build up into tangles and plaques- causing brain cells to die and the brain to shrink.

For years, scientists have been using animal models to study this disease. In this study, scientists used post-mortem brain samples from Alzheimer’s patients. They also used PET scans from living patients, who ranged from those with mild cognitive impairment to those with late-stage Alzheimer’s disease.

Using these samples, scientists tracked the aggregation of tau.

Scientists combined five different datasets and applied them to the same mathematical model to observe the mechanism controlling the rate of progression in Alzheimer’s disease. They found the replication of aggregates in individual brain regions and not the spread of aggregates from one region to another.

The study could lead to a better understanding of the progress of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Dr. Georg Meisl from Cambridge‘s Yusuf Hamied Department of Chemistry, the paper’s first author, said, “The thinking had been that Alzheimer’s develops in a way that’s similar to many cancers: the aggregates form in one region and then spread through the brain. But instead, we found that when Alzheimer’s starts, there are already aggregates in multiple regions of the brain, and so trying to stop the spread between regions will do little to slow the disease.”

Co-senior author Professor Tuomas Knowles, also from the Department of Chemistry, said, “This research shows the value of working with human data instead of an imperfect animal model. It’s exciting to see the progress in this field – fifteen years ago, the basic molecular mechanisms were determined for simple systems in a test tube by us and others. Still, now we’re able to study this process at the molecular level in real patients, which is an important step to one-day developing Alzheimer’s disease treatments.”

Co-senior author Professor Sir David Klenerman from the UK Dementia Research Institute at the University of Cambridge said, “The replication of tau aggregates is surprisingly slow – taking up to five years. Neurons are surprisingly good at stopping aggregates from forming, but we need to find ways to make them even better if we develop an effective treatment. It’s fascinating how biology has evolved to stop the aggregation of proteins.”

Knowles said, “The key discovery is that stopping the replication of aggregates rather than their propagation is going to be more effective at the stages of the disease that we studied.”

Journal Reference:

- Georg Meisl et al. ‘In vivo rate-determining steps of tau seed accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease.’ Science Advances (2021). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abh1448