Globally almost one in every 500 babies are born with extra fingers or toes. This condition is also known as Polydactyly.

The extra fingers are usually smaller and abnormally developed than normal. The vast majority of occurrences of polydactyly are sporadic, meaning that the condition occurs without an apparent cause—but some may be due to a genetic defect or underlying hereditary syndrome.

An examination into polydactyly has focused for the most part on the genetic transformation behind it – yet until now, no one has considered how the brain and body make up for the additional workload.

However, new research from the University of Freiburg in Germany, Imperial College London, and the Université de Lausanne and EPFL in Switzerland, has found that, in people with well-formed extra digits, the brain can allocate dedicated areas. In this study, the brain’s extra contribution made the extra fingers as useful as standard digits.

It suggests polydactyl brains could teach us how our brains adapt to extra workloads. The discoveries likewise present an argument for keeping the additional toes or fingers some people are born on the off chance that they are well-shaped and useful.

Each of our fingers is joined to the hand by dedicated tendons, moved by dedicated muscles, and linked to dedicated nerves – all of which are specific to each finger. These are controlled by dedicated brain areas specific to each finger in the motor cortex – the brain region responsible for movement.

The researchers wanted to find out how extra digits fit into this arrangement.

Senior author Professor Etienne Burdet, of Imperial’s Department of Bioengineering, who carried out this study with his colleagues in Germany and Switzerland, said: “Extra fingers and toes are traditionally seen as a birth defect, so nobody has thought to study how useful they might really be.”

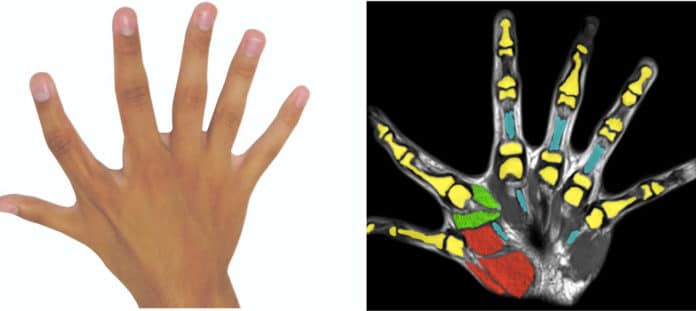

During the study, scientists studied two people – a 52-year-old woman and her 17-year-old son – who both have six fingers on each of their hands, with a well-formed extra finger between each thumb and forefinger.

They studied benefits of having extra fingers by exploring objects with their hands, tie shoelaces, type on their phones, and play custom-made video games – movements classed a ‘manipulation’. They then analyzed and compared movements to the movements of control subjects with five fingers on each hand. During manipulation, high-resolution functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) monitored their brain activity.

Scientists found that the extra polydactyl had their own dedicated tendons, muscles, and nerves, as well as extra corresponding brain regions in the motor cortex.

Also, polydactyl participants showed better performance at many tasks than their non-polydactyl counterparts. For instance, they were able to perform some tasks, like tying shoelaces, with only one hand, where two are usually needed.

The study also found that controlling those extra fingers requires extra brain power.

Professor Burdet said: “The polydactyl individual’s brains were well adapted to controlling extra workload, and even had dedicated areas for the extra fingers. It’s amazing that the brain has the capacity to do this seemingly without borrowing resources from elsewhere.”

Scientists noted, “the findings might serve as a blueprint for the developing artificial limbs and digits to expand our natural movement abilities. For example, giving a surgeon control over an extra robotic arm could enable them to operate without an assistant.”

Lead author Professor Carsten Mehring of the University of Freiburg said: “Perhaps we can tap into the brain resources demonstrated in this study to make this possible.”

However, he also warned that people with robotic extra limbs may not achieve as good control as observed in the two polydactyl subjects. Any robotic digits or limbs wouldn’t have dedicated bone structure, muscles, tendons or nerves.

Professor Mehring added: “In our study, the extra digits have been trained in the subjects since birth. This does not necessarily mean that similar functionality can be achieved when artificial limbs are added on later in life.

“Yet, people with polydactyly provide a unique opportunity to analyze the neural control of extra limbs and the possibilities to boost sensorimotor control.”

The German Research Foundation (DFG), the European Commission, the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council(EPSRC), and the Swiss National Science Foundation funded the research.

Scientists published their findings in the journal Nature Communications.