Food systems emerged with the dawn of civilization when agriculture, including the domestication of animals, set the stage for permanent settlements. Since agriculture began, food systems have constantly evolved, each change bringing new advantages and challenges and ever-greater diversity and complexity.

The emergence of city-states has been a major driver of food system changes, bringing together large populations within defined boundaries and requiring complex governance to deliver sufficient quantities and quality of food. Current food systems is a multi-stage and complex chain which can involve many companies internationally.

At each stage of the process a product can be altered from what it is supposed to be, either intentionally or by accidental contamination—without the next companies, retailers or consumers down the chain being aware.

On the other side, today’s consumers become health conscious. They are looking more closely at what’s really in their food – especially given the numerous scandals that have come to light.

To address the problem of such food fraud, EPFL scientists at EPFL’s Digital Epidemiology Lab launched the Open Food Repo DNA initiative to develop a system that would enable consumers to sequence the DNA in processed foods and identify every single ingredient. The aim is to develop easy and affordable protocols (like a recipe) for genetic sequencing of processed food with the long-term aim that anyone would be able to test their food at home and identify the ingredients of animal or plant origin.

The activity will involve adding DNA information to the Open Food Repo, an open-source repository of nutritional data on 45,000 bar-coded food products in Switzerland. The Open Food Repo was additionally made by the Digital Epidemiology Lab.

All living organisms store genetic information using the same molecules — DNA and RNA. These are the molecules that contain the information necessary for organisms to live and grow. DNA sequencing is the process of determining the sequence of this genetic information, but it is expensive and extensive endeavor which is done in big, well-equipped laboratories either in private companies or state institutions such as universities.

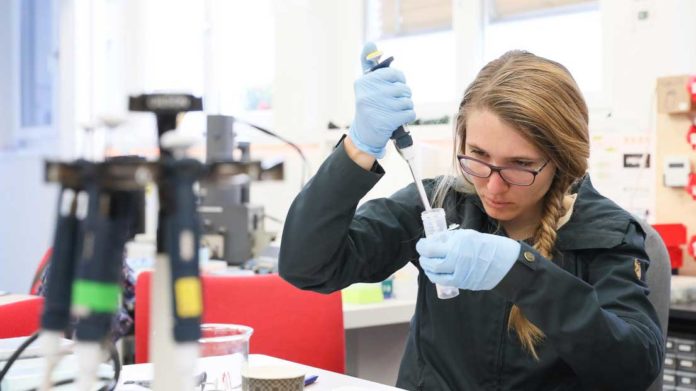

Modern advancements have overcome this barrier and made the technique technically and financially feasible for smaller organizations like community laboratories. It also includes the Open Food Repo DNA initiative. Since last fall, scientists have been working on a new method that spells out DNA sequencing instructions like the steps in a recipe, employing techniques like high-throughput sequencing and DNA barcoding – which is the process of examining just a small section of an organism’s DNA.

Capable of being read like a barcode, these sections are similar enough across all organisms to be easily extracted from an entire DNA chain, yet different enough that they can be used to identify individual plants and animals.

Pietro Cattaneo, Product Development Scientist at SwissDeCode said, “The first step is to mix all the food ingredients together thoroughly with a mixer. Then we extract a section of DNA using specific chemical compounds at high temperatures. The extracted DNA section is amplified to make numerous copies and then sequenced by converting the individual molecules into electric signals, which are translated into a DNA code.”

A group of consumers tested the system at a workshop held in the Hackuarium community laboratory last Saturday, 4 May. Participants included both scientists and open-science advocates, and they spent the day extracting and amplifying the DNA from food products ranging from paprika-flavored potato chips and tuna sandwiches to falafel and pesto sauce. The food’s DNA sequences will be sent to the participants in the upcoming days.

Barbara Pfenniger, the head of the food department of the Fédération Romande des Consommateurs said, “A growing number of products in supermarkets today are processed, and consumers want to know exactly what they’re eating. What’s great about this initiative is that it will empower people to analyze their food themselves.”

“Open-science projects also have a snowball effect – the more participants they have, the more people get interested in them. And in this case, we are encouraging people to look more critically at the food everyone eats.”

Talia Salzmann, who is heading up the initiative at the Digital Epidemiology Lab said, “We plan to hold more workshops at the Hackuarium in order to test and improve our system and make it easier to use. Then we will roll out the workshops at other community labs in Switzerland and abroad.”

Scientists, through this initiative, hopes to foster dialogue on how new technology can be leveraged to help people eat healthier, improve transparency in the food industry.