Astronomers have known for right around a century that the universe is extending, which means the distance between galaxies over the universe is ending up perpetually massive consistently. Be that as it may, precisely how quick universe is extending, a value known as the Hubble constant, has remained adamantly elusive

Astronomers have recently come up with a measurement for the universe’s expansion using an entirely different sort of star than past undertakings. They suggested that the space between galaxies is stretching faster than scientists would expect.

As more research focuses on the discrepancy among predictions and observations, scientists are thinking about whether they may need to concoct another model for the fundamental physics of the universe to clarify it.

University of Chicago professor Wendy Freedman said, “The Hubble constant is the cosmological parameter that sets the absolute scale, size, and age of the universe; it is one of the most direct ways we have of quantifying how the universe evolves.”

“The discrepancy that we saw before has not gone away, but this new evidence suggests that the jury is still out on whether there is an immediate and compelling reason to believe that there is something fundamentally flawed in our current model of the universe.”

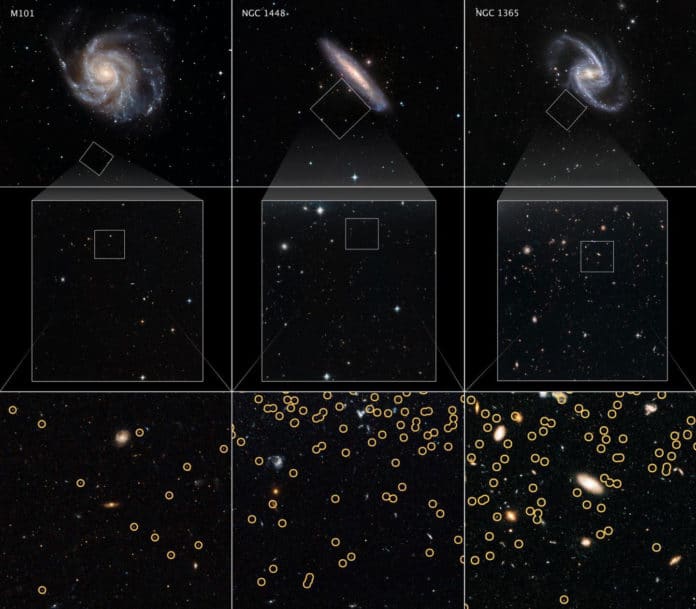

During the study, scientists used a kind of star known as a red giant. Their new observations, made using Hubble, indicate that the expansion rate for the nearby universe is just under 70 kilometers per second per megaparsec (km/sec/Mpc). One parsec is equivalent to 3.26 light-years distance.”

“Their new observations, made using Hubble, indicate that the expansion rate for the nearby universe is just under 70 kilometers per second per megaparsec (km/sec/Mpc). One parsec is equivalent to 3.26 light-years distance.”

Scientists also built a model called Cosmic Microwave Background- a model based on the rippling structure of light leftover from the big bang. Using Planck measurements, scientists were able to predict how the early universe would likely have evolved into the expansion rate astronomers can measure today.

Scientists calculated value of 67.4 km/sec/Mpc, in significant disagreement with the rate of 74.0 km/sec/Mpc measured with Cepheid stars.

Freedman said, “Astronomers have looked for anything that might be causing the mismatch. Naturally, questions arise as to whether the discrepancy is coming from some aspect that astronomers don’t yet understand about the stars we’re measuring, or whether our cosmological model of the universe is still incomplete. Or maybe both need to be improved upon.”

Freedman’s group looked to check their outcomes by setting up another and altogether free way to the Hubble constant utilizing a different sort of star.

The Hubble constant is calculated by comparing distance values to the apparent recessional velocity of the target galaxies—that is, how fast galaxies seem to be moving away. The team’s calculations give a Hubble constant of 69.8 km/sec/Mpc—straddling the values derived by the Planck and Riess teams.

Freedman said, “Our initial thought was that if there’s a problem to be resolved between the Cepheids and the Cosmic Microwave Background, then the red giant method can be the tie-breaker. But the results do not appear to favor one answer over the other strongly say the researchers, although they align more closely with the Planck results.”

The new paper accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.