Helicobacter pylori chronically colonize the stomach and are strongly associated with gastric cancer. Its concomitant occurrence with helminths such as schistosomes has been linked to reduced cancer incidence, presumably due to suppression of H. pylori-associated pro-inflammatory responses.

Schistosomiasis is an acute and chronic parasitic disease caused by blood flukes (trematode worms) of the genus Schistosoma. Estimates show that at least 240 million people worldwide are afflicted with schistosomiasis.

People become tainted when larval forms of the parasite – discharged by freshwater snails – enter the skin during contact with infested water.

In the body, the larvae develop into adult schistosomes. Adult worms live in the veins where the females release eggs. Some of the eggs are passed out of the body in the feces or urine to continue the parasite’s lifecycle. Others become caught in body tissues, causing immune reactions and progressive damage to organs.

A team headed by Prof. Clarissa Prazeres da Costa and Prof. Markus Gerhard of the Institute for Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Hygiene at Technical University of Munich has completed the first study of the effects of simultaneous infection with blood flukes (schistosomes) and the bacterium Helicobacter pylori – a reasonably common occurrence in some parts of the world.

They also identified a complex interaction that resulted – among other impacts – in a weakening of the unfavorable effect of the pathogens acting exclusively.

Scientists conducted their study on the mice and observed what happens in a co-infection with Helicobacter pylori and Schistosoma mansoni.

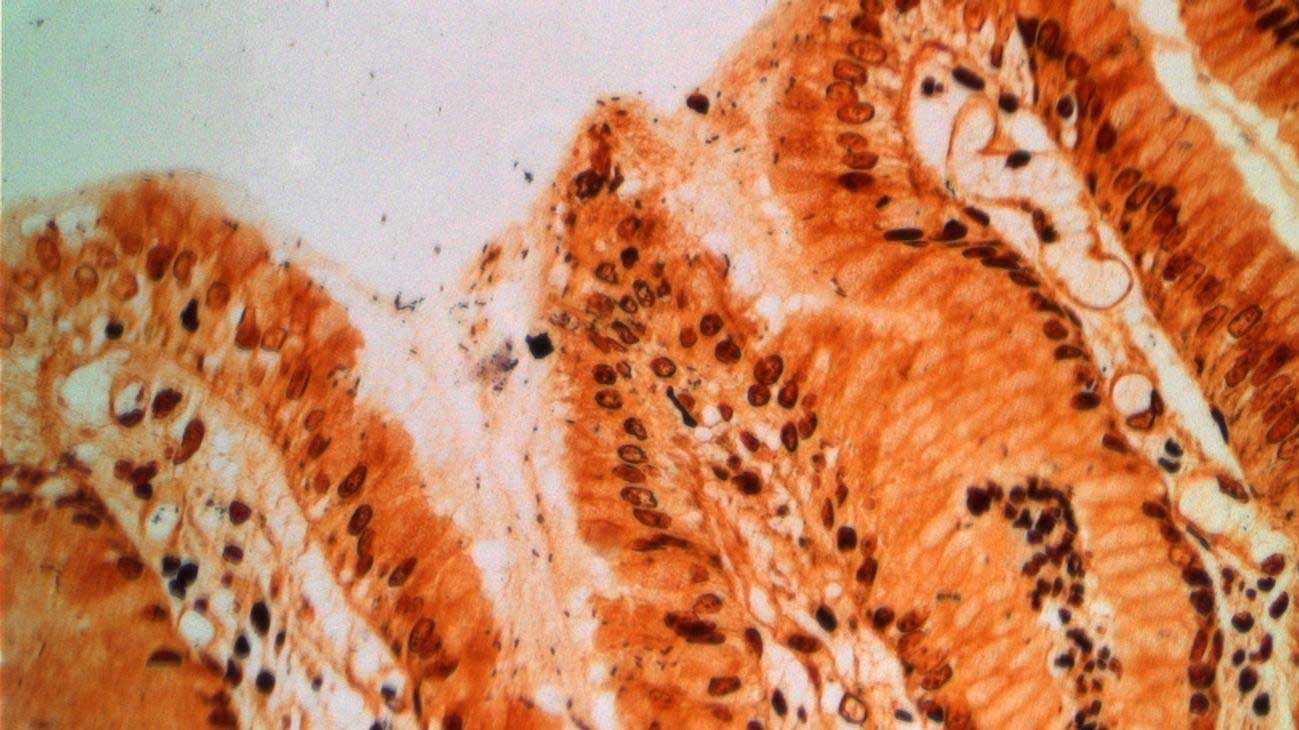

Image: Markus Gerhard / TUM

In a schistosomiasis infection, the initial infection is followed by an acute phase, supplanted around five weeks after the fact by a chronic phase. In their study, Prazeres da Costa and Gerhard demonstrate that fewer T-cells are found in the stomach during the acute phase of schistosomiasis. In hosts infected only by Helicobacter pylori, these immune cells are progressively various in the stomach and cause inflammation there.

Markus Gerhard said, “We show that the schistosomiasis drives an increase in chemokine levels in the liver. The chemokines attract the T-cells and, in a sense, misdirect them to the liver. This leads to a reduction in stomach inflammation. This effect fades away when the chronic phase begins, however. While hosts infected with schistosomiasis alone often suffer liver damage during that phase, this is less common with co-infections.”

Scientists detected elevated quantities of the signaling protein IL-13dRa2 in the blood of mice infected with the bacteria.

Prof. Clarissa Prazeres da Costa said, “IL-13dRa2 can provide protection against cirrhosis and can even reverse tissue changes. We, therefore, believe that they could play a decisive role to reduce the extent of liver cirrhosis in co-infections.”

“In everyday life, many people are repeatedly re-infected with schistosomes because they come into frequent contact with water containing the worms. „As a result, there is no time limit on the diversion of T-cells to the liver because the chronic and acute phases co-occur.”

Markus Gerhard said, “At first glance, the interactions in case of a co-infection may look like a positive side effect: Although the infected individual is suffering from two illnesses, the harmful effects of both are seemingly reduced. Co-infections can have other consequences, however. For example, the changed immune response can limit the effectiveness of vaccines.”

“We urgently need more studies on their effects and ways of dealing with them, for example, to develop new and more effective vaccination strategies.”