Transplanted tissue regularly goes under attack from the body’s immune system and struggles to survive in the hostile host environment. This has resulted in a shortage of suitable transplants for patients with dysfunctional cells and organs, inciting specialists to devise alternative strategies.

Since several years, scientists are working on an idea to coat cells from human donors – and even animals – with a semi-permeable gel that protects them from attack and means patients can receive the tissue without having to take immunosuppressive drugs.

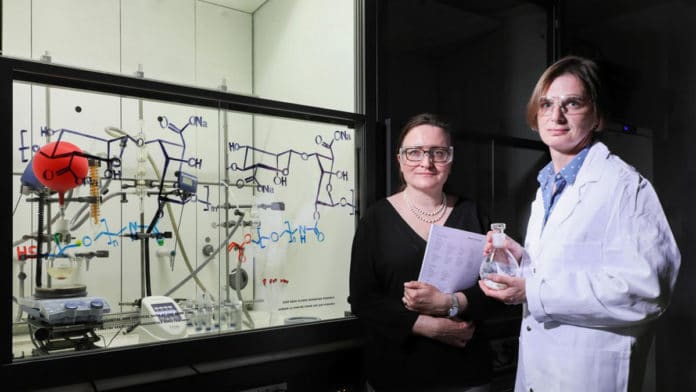

Such innovation is widely studied in pancreatic islet cell transplantation and seems to have promising applications for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. A gel created by an EPFL group, driven by Sandrine Gerber, has been only licensed to Geneva-based startup Cell-Caps SA.

The gel composed of sodium alginate, a gum extracted from the cell walls of brown algae, and water-soluble polymers. Acts as a selective filter, it works by blocking immune-system cells and antibodies while allowing oxygen and other molecules to pass through, in both directions, so that the coated cells can metabolize – and, ultimately, survive.

It also allows the cells to discharge metabolic byproducts such as insulin.

The gel then forms a soft cocoon that mechanically protects the cells. This it reduces the chances of inflammation in the host body – a process that causes scarring and adversely affects transplant function.

Scientists added active ingredients such as ketoprofen to the gel. Ketoprofen is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory that stops inflammation at its early stages. They then bound all the parts to the gelatinous structure.

Scientists then developed a special process that releases the drug steadily and in a targeted, controlled fashion, meaning they could add more of it to the gel.

Aside from pancreatic islet cell transplants, the technology has potential applications for other tissues and in other clinical fields, such as the treatment of acute liver failure.

Sandrine Gerber, a co-author of the study, said, “Part of the hydrogel’s appeal to the private sector stems from the fact that it is relatively straightforward to make. Indeed, the production process is included in the licensing agreement. We’ll have to carry out further tests to measure the gel’s long-term performance.”

“We’ll also need a more reliable source of transplantable cells that we can reproduce. It could be another five or even eight years before the gel is used in clinical settings.”

Natalia Giovannini, technology transfer manager at TTO, said, “Aside from pancreatic islet cell transplants, the technology has potential applications for other tissues and in other clinical fields, such as the treatment of acute liver failure. We think this new gel holds real promise.”

“We’ve had a lot of interest from elsewhere in the private sector, and we’re currently holding talks about a new licensing agreement.”

The organization, established by scientists at Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) who specialize in pancreatic islet cell transplantation, works intimately with InsuLéman, a diabetes research foundation. Because of an enabled grant from EPFL’s Technology Transfer Office (TTO), the researchers had the option to permit their innovation only to Cell-Caps.

This latest research, published in ACS Applied Polymer Materials.