Certain viruses—known as satellites—need their host organism to finish their life cycle, while other viruses—known as helpers—also depend on it. The satellite virus needs the aid to either create its capsid, a protective encasement for its genetic material or to facilitate DNA replication. Until now, there have been no documented instances of a satellite physically attaching itself to a helper. Instead, these viral interactions necessitate the satellite and the helper to be near one another, if only momentarily.

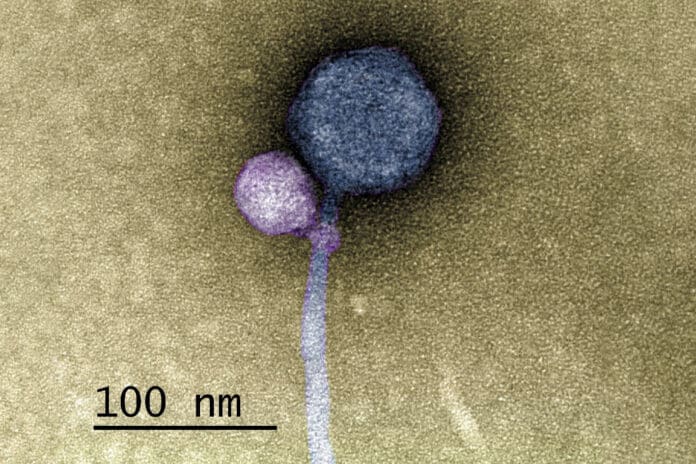

For the first time, a UMBC team and colleagues from Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) have observed a satellite bacteriophage regularly attaching to a helper bacteriophage at the “neck” of the virus, where the capsid joins the tail.

The research began as a standard semester in the SEA-PHAGES program, an investigative curriculum in which students receive environmental samples, separate bacteriophages, send them off for sequencing and analyze the results using bioinformatics tools. The journey started when the University of Pittsburgh sequencing lab discovered contamination in the UMBC sample that was supposed to contain the MindFlayer virus.

The sample included one large and a small sequence, which didn’t map to anything known. The team reran the isolation, sent it out for sequencing—and got identical results.

Scientists used electron microscopy to capture images, where 80 percent (40 out of 50) helpers had a satellite bound at the neck. Some individuals lacked residual satellite tendrils at the neck. They have the appearance of “bite marks.”

Tagide deCarvalho, assistant director of the College of Natural and Mathematical Sciences core facilities and first author on the new paper, said, “When I saw it, I was like, ‘I can’t believe this.’ No one has ever seen a bacteriophage—or any other virus—attach to another virus.”

Scientists examined the genomes of the satellite, helper, and host after the first observations, which provided more information on this hitherto unidentified viral relationship. Once within the cell, the majority of satellite viruses have a gene that enables them to merge with the genetic material of the host cell. This makes it possible for the satellite to procreate the next time an assistant enters the cell. When the host cell divides, it duplicates both its own DNA and that of the satellite.

The WashU bacteriophage sample contained a helper and a satellite. Unlike other satellite-helper systems that have been seen before, the WashU satellite contains an integration gene and does not bind directly to its helper.

But the satellite in the UMBC sample—dubbed MiniFlayer by the students who isolated it—is the first instance of a satellite that lacks an integration gene that is currently known to exist. Its survival depends on staying close to its helper, MindFlayer, each time it enters a host cell since it is unable to integrate into the DNA of the host cell.

Ivan Erill, professor of biological sciences, said, “Attaching now made total sense because otherwise, how are you going to guarantee that you are going to enter into the cell at the same time?”

Further bioinformatics investigation demonstrated the long-term coevolution of MindFlayer and MiniFlayer. There may be many more examples of this type of association yet to be found, as this satellite has been tuning in and optimizing its genome to be associated with the helper for at least 100 million years.

Journal Reference:

- deCarvalho, T., Mascolo, E., Caruso, S.M. et al. Simultaneous entry as an adaptation to virulence in a novel satellite-helper system infecting Streptomyces species. ISME J (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41396-023-01548-0