Alzheimer’s Disease is one of the biggest concerns many of us have as we get older. By leading a brain-healthy lifestyle, you may be able to prevent the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and slow down. Scientists have debated for a long why there seems to be a link between an individual’s higher levels of education and lower rates of Alzheimer’s disease in later life.

New research from Johns Hopkins Medicine suggests that smarter, more educated people aren’t protected from the disease, but do get a cognitive “head start” that may keep their minds functioning better temporarily.

Though the previous study consistently discovered a correlation between high education and low rate of dementia, it has been unclear whether this link was related to actual structural differences in the brain, or if it simply was a case of more education giving individuals a kind of cognitive head start.

To examine this discrimination, researchers looked at data from a study following thousands of subjects for several decades, from mid-life to later-life.

The findings suggest (don’t prove) that exercising your brain might help keep people cognitively functional longer, but there will be no inevitable reduction in Alzheimer’s disease.

“Our study was designed to look for trends, not prove cause and effect, but the major implication of our study is that exposure to education and better cognitive performance when you’re younger can help preserve cognitive function for a while even if it’s unlikely to change the course of the disease,” says Rebecca Gottesman, M.D., Ph.D., professor of neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

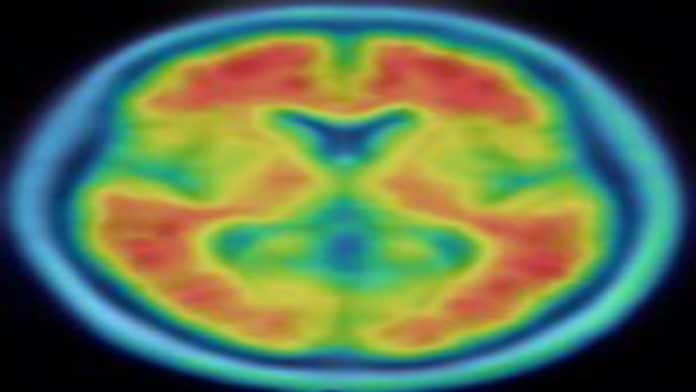

For the study, the researchers focused on a group of 331 participants without dementia, who all underwent brain imaging to evaluate levels of amyloid beta in the brain, the main pathological characteristic associated with the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Some 54 had less than high school education, 144 had completed high school or earned their GED diploma, and 133 had some college or more formal education.

The participants were also cognitively tested several times over a 20-year period to track any decline.

The researcher team found that education level has no association with the rate of pathological progression in Alzheimer’s disease. And hence, regardless of the level of education of a person, the progression of amyloid beta was the same.

However, cognitive testing revealed a distinct correlation between education levels and intellectual function, despite amyloid beta accumulations in the brain. This means college-educated subjects performed better on cognitive tests in later years compared to subjects with lower levels of education, even though both groups displayed similar amyloid beta levels. The distinction is particularly important for researchers trailing experimental treatments and evaluating the efficacy of potential new drugs.

This suggests that cognitive tests may not be a useful way to objectively evaluate how effective a new treatment may be, as individuals with similar levels of Alzheimer’s pathology could demonstrate different cognitive scores depending on education levels.

“Our data suggest that more education seems to play a role as a form of cognitive reserve that helps people do better at baseline, but it doesn’t affect one’s actual level of decline,” says Gottesman. “This makes studies tricky because someone who has good education may be less likely to show a benefit of an experimental treatment because they are already doing well.”

Gottesman noted, to overcome this problem in future studies cognitive performance must be evaluated in individuals over time instead of measured at a single point. This would hopefully account for the variations in individual cognitive responses to prospective treatments. The research also suggests while higher levels of education may keep one’s brain cognitively functional, at least temporarily, it doesn’t fundamentally alter the pathological course of the disease.

Additional authors include Andreea Rawlings of Oregon State University, A. Richey Sharrett and Dean Wong of Johns Hopkins, Thomas Mosley of the University of Mississippi and David Knopman of the Mayo Clinic.

The findings are published in the April issue of the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.