Scientists often look at microscopic damage to teeth to infer what an animal is eating. In a new study, scientists took a gander at microscopic interactions between food particles and enamel. They found that the hardest plant tissues scarcely wear down primate teeth, suggesting that even hard plants may have included in their diet.

The study conducted by the scientists from Washington University in St. Louis could have implications for reconstructing diet, and potentially for our interpretation of the fossil record of human evolution.

Adam van Casteren, lecturer in biological anthropology in Arts & Sciences, said, “We found that hard plant tissues such as the shells of nuts and seeds barely influence microwear textures on teeth.”

“Traditionally, eating hard foods is thought to damage teeth by producing microscopic pits. But if teeth don’t demonstrate elaborate pits and scars, this doesn’t necessarily rule out the consumption of hard food items.”

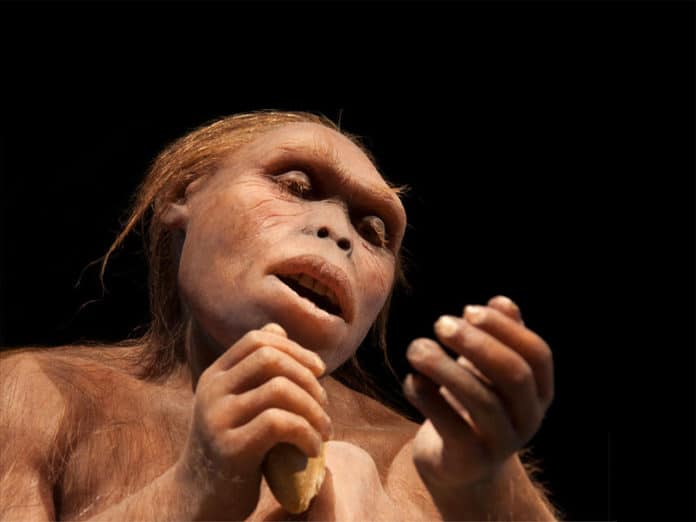

Humans diverged from non-human apes around 7,000,000 years back in Africa. The new examination tends to address the debate on what some early ancestors, the australopiths, were eating. These hominin species had enormous teeth and jaws, and likely huge chewing muscles.

Van Casteren said, “All these morphological attributes seem to indicate they could produce large bite forces and therefore likely chomped down on a diet of hard or bulky food items such as nuts, seeds or underground resources like tubers.”

For this examination, the analysts attached small bits of seed shells to a probe that they dragged across enamel from a Bornean orangutan molar tooth.

They made 16 “slides” representing contacts between the enamel and three distinctive seed shells from woody plants that are a part of modern primate diets. The scientists then hauled the seeds against enamel at forces comparable to any chewing activity.

Scientists found that even at such force, there were no large pits, scratches, or fractures in the enamel. There were a few shallow grooves. However, scientists didn’t observe anything that indicates that hard plant tissues could contribute thoughtfully to dental microwear. The seed fragments themselves, be that as it may, gave indications of degradation from being rubbed against the enamel.

This information is useful for anthropologists who are left with only fossils to try to reconstruct ancient diets.

Van Casteren said, “We aimed to understand the underlying mechanics of how these scars on the tooth surface are formed. If we can fathom these fundamental concepts, we can generate more accurate pictures of what fossil hominins were eating.”

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.