Marine cone snails have attracted researchers from all fields, but early life stages have received limited attention due to difficulties accessing or rearing juvenile specimens. Because of these limitations, the ecology and biochemistry of juvenile cone snails have been largely overlooked.

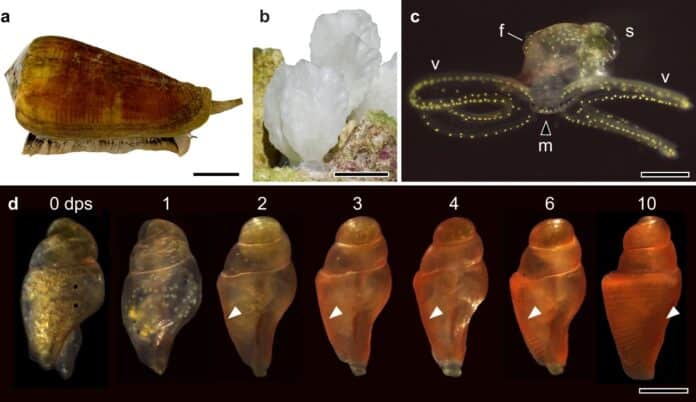

In order to find new venoms for drug development, the University of Queensland researchers have reared deadly cone snails in a lab aquarium for the first time. Researchers cultured Conus magus from egg capsules to hatching larvae and through metamorphosis to carnivorous juveniles.

After undergoing metamorphosis, juvenile C. magus was seen only to hunt polychaete worms utilizing teeth that resembled those of their ancestors and a special repertoire of venoms before switching to fish-hunting as adults. Researchers discovered changes in the diet, behavior, and toxicity of the Conus magus using various experimental techniques.

Cone snail juveniles kill their prey with a different combination of venoms than adult cone snails. This is a diverse and untapped category of molecules that can be looked at as drug discovery leads.

Professor Richard Lewis from UQ’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience said, “A lot of our success with venom molecules has been in developing pain medications, but depending on the pharmacology, we’ll see if it has therapeutic potential for any of the disease classes.”

“The researchers were also surprised to find juvenile cone snails didn’t feed on fish like the adults of the species.”

“The juveniles would only eat polychaete worms, which they catch using a specific hunting technique we named ‘sting and stalk.'”

“They jab the worm with a harpoon-like structure before injecting it with venom to subdue it. The juvenile snail then slowly stalks the worm and sucks it up, like a small piece of spaghetti.”

Cone snails consume a certain kind of microalgae as larvae, but their diet changes after they metamorphose into half-millimeter-long juveniles.

Researchers noted, “Our results show how laboratory-reared specimens can provide new insights into the ecology of secretive life stages and highlight the potential of juvenile cone snails as an untapped source of novel bioactive venom peptides that would otherwise only be accessible through exon capture or genome sequencing.”

Journal Reference:

- Rogalski, A., Himaya, S.W.A. & Lewis, R.J. Coordinated adaptations define the ontogenetic shift from worm- to fish-hunting in a venomous cone snail. Nature Communications 14, 3287 (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-38924-5