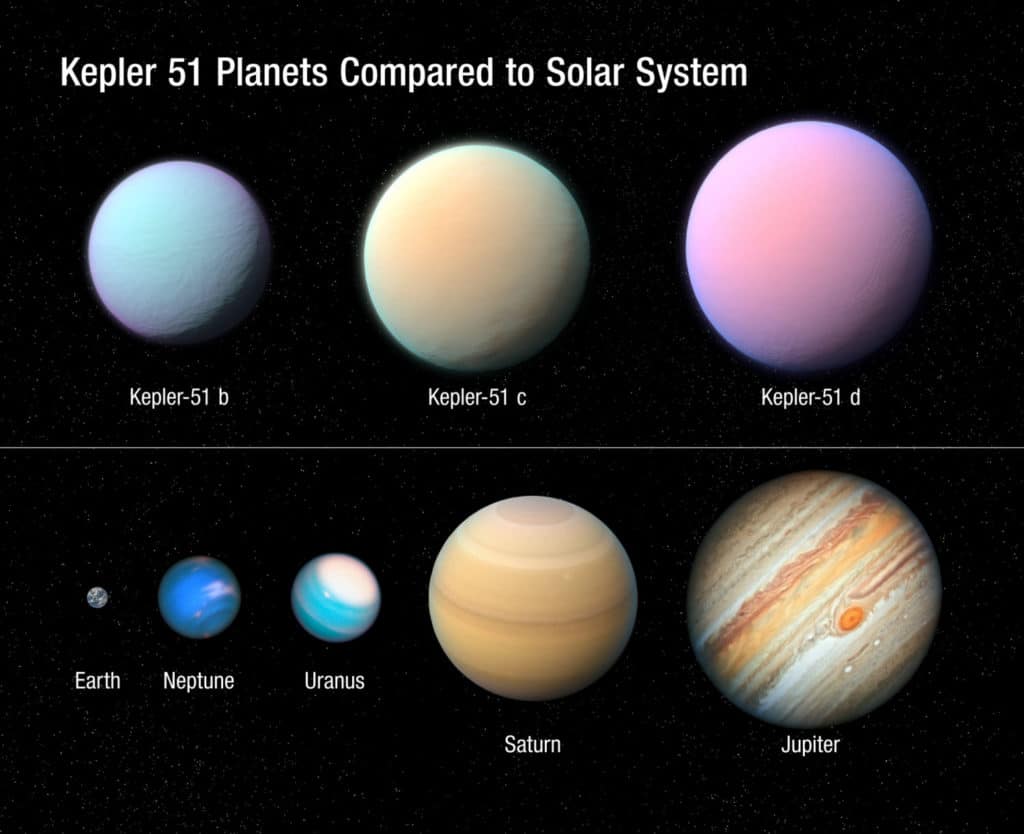

Kepler 51 is a moderately young (500 Myr) G-type star that hosts three Jupiter-sized planets with orbital periods of 45, 85, and 130 days. All these planets have unusually low masses. According to NASA Exoplanet Archive, these planets are known as the lowest-density planets.

Recently, the Kepler mission revealed a class of planets known as “superpuffs,” with masses only a few times larger than Earth’s but radii larger than Neptune, giving them very low mean densities. These planets are as lightweight as cotton candy.

A new study by the University of Colorado Boulder set out to uncover the components that make up the exoplanets’ atmospheres—and to provide further clues around how such low-density planets may have formed in the first place.

Zachory Berta-Thompson, an assistant APS professor and a co-author of the new research, said, “This is an extreme example of what’s so cool about exoplanets in general. They allow us to study worlds that are very different than ours, but they also place the planets in our solar system into a broader context.”

“Super-puff planets are relatively rare in the galaxy—fewer than 15 have been recorded so far. Their discovery was “straight-up contrary to what we teach in undergraduate classrooms.”

Using Hubble Space Telescope, scientists get a closer look at Kepler 51 star system that is located about 2,400 lightyears, or thousands of trillions of miles, from Earth and is a relative youngster at 500 million years old. They then calculated the trio’s masses and densities.

What they found is- all three planets had a density less than 0.1 grams per cubic centimeter of volume—almost identical to the sweet pink treats you can buy at any fairground.

Libby-Roberts said, “We knew they were low density. But when you picture a Jupiter-sized ball of cotton candy—that’s low density.”

Scientists now want to peer into the planets’ atmospheres. And it’s not that much easy as the atmospheres of the super-puffs weren’t transparent at all. Instead, they appeared to be shrouded by a high-altitude layer of something opaque.

Libby-Roberts said, “It sent us scrambling to come up with what could be going on here. We expected to find water, but we couldn’t observe the signatures of any molecule.”

Using computer simulations and other tools, scientists were able to confirm that the Kepler 51 planets are mostly hydrogen and helium by mass. These lightweight gases give these worlds their puffiness.

Other observations by the scientists revealed that the Kepler 51 planets seemed to be shedding gas at a rapid pace. Meanwhile, the innermost of the three worlds, for example, dumps an estimated tens of billions of tons of material into space every second. If this trend continues, the planets could shrink considerably over the next billion years, losing their candy-like cotton puffiness.

Libby-Roberts said, “People have been struggling to find out why this system looks so different than every other system. We’re trying to show that it does look like some of these other systems.”

This study will appear in The Astronomical Journal. Other co-authors on the new study include researchers from the University of Amsterdam, Princeton University, the University of Texas at Austin, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, California Institute of Technology, University of Chicago, University of California, Santa Cruz, Arizona State University and Netflix.