Accounting for both climate change and natural disturbances—which typically result in greenhouse gas emissions—is necessary to begin managing forest carbon sequestration. Gaining a complete understanding of forest carbon dynamics is, however, challenging in systems characterized by historic over‐utilization, diverse soils and tree species, and frequent disturbance.

There are various models available including satellite imagery of earth’s vegetation, measurements of carbon dioxide in the air and computer models all help scientists understand how climate is affecting carbon dynamics and the world’s forests. But these methods stretch back only decades, limiting our picture of long-term changes.

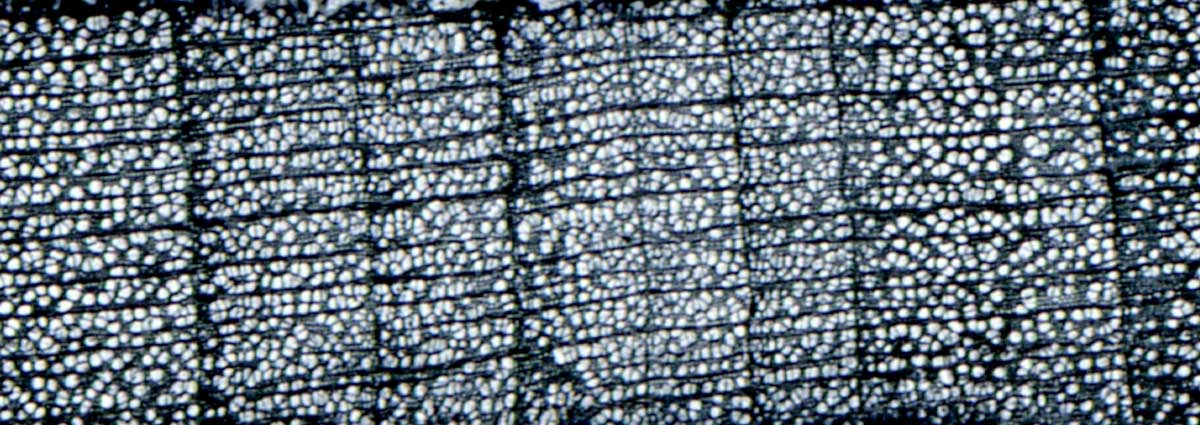

In a new study by the co-authored by HF Senior Ecologist Neil Pederson with Columbia University, ETH Zürich, and elsewhere, scientists suspected that how information revealed by a new method of analyzing tree rings matches the story told by more high-tech equipment over the short term. Since trees are enduring, thinking back in their rings with this new methodology may add decades or even hundreds of years to our comprehension of carbon storage and how climate change is affecting forests.

To test whether tree rings are a good proxy for modern satellite and other data, the scientists examined ring samples from two widespread tree species — tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) and northern red oak (Quercus rubra). Both species growing in three climatically different regions of the eastern United States.

By analyzing the isotopes of carbon and oxygen stored in the rings, they compared the trees’ own picture of forest productivity to estimates derived from satellites. They found strong agreement each year, and over time.

Their analysis unveiled that the changes in annual forest growth in this region were linked to moisture availability.

Laia Andreu-Hayles, a tree-ring researcher at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory said, “Our method showed that the productivity of a forest can be estimated using information from just five trees. The stable isotopes measured in tree rings are highly sensitive to tracking moisture.”

Neil Pederson, an ecologist at Harvard Forest said, “To take full advantage of the new method, many more sites over wider areas would have to be sampled. When we put tree ring data to work in historical climate models, we find that the models are more powerful when more species are included.”

“I suspect this might also be the case when we use models to look forward, to future forest productivity and carbon storage.”

The study is reported in the journal Nature Communications.