Degeneration of the optic nerves, DOA typically starts to cause patients’ symptoms in their early adult years. These include moderate vision loss and some color vision defects, but severity varies, symptoms can worsen over time, and some people may become blind. There is currently no way to prevent or cure DOA.

A gene (OPA1) gives directions to making a protein found in cells and tissues all through the body, which is crucial for maintaining proper function in mitochondria, which are the energy producers in cells.

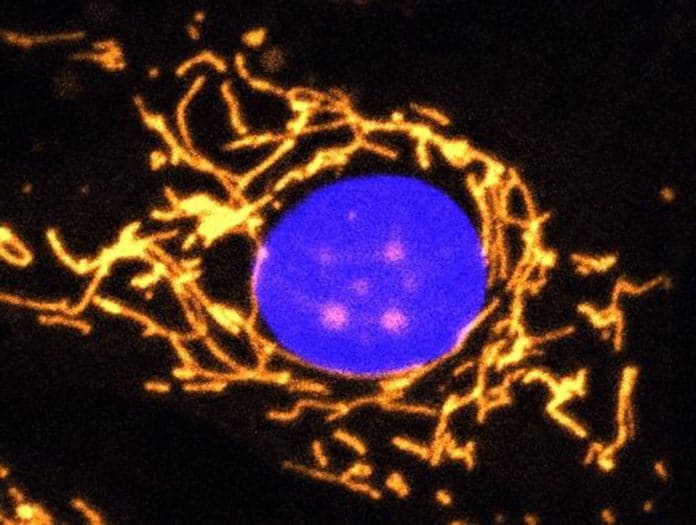

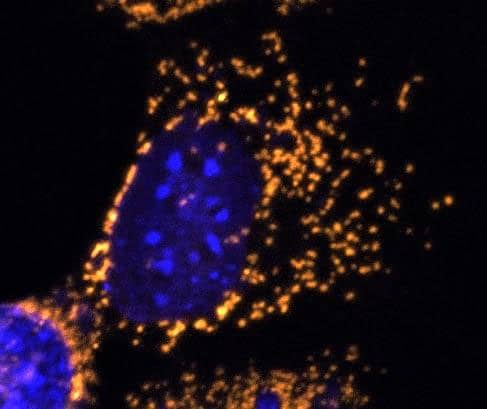

Without the protein made by OPA1, mitochondrial function is imperfect, and the mitochondrial network in healthy cells is well interconnected is highly disrupted.

For those living with DOA, it is mutations in OPA1 and the dysfunctional mitochondria that are liable for the disorder’s onset and progression.

In collaboration with clinical teams in the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital and the Mater Hospital, scientists from Trinity College Dublin have developed a new gene therapy for eye disease. This new approach offers promise for one day treating an eye disease that leads to a progressive loss of vision and affects thousands of people worldwide.

In experiments with mice, the gene therapy successfully protected mice’s visual function who were treated with a chemical targeting the mitochondria and were consequently living with dysfunctional mitochondria.

The scientists also found that their gene therapy improved mitochondrial performance in human cells that contained mutations in the OPA1 gene, offering hope that it may be useful in people.

Dr. Daniel Maloney from Trinity’s School of Genetics and Microbiology said, “We used a clever lab technique that allows scientists to provide a specific gene to cells that need it using specially engineered non-harmful viruses. This allowed us to directly alter the functioning of the mitochondria in the cells we treated, boosting their ability to produce energy which in turn helps protects them from cell damage.”

“Excitingly, our results demonstrate that this OPA1-based gene therapy can potentially provide benefit for diseases like DOA, which are due to OPA1 mutations, and also possibly for a wider array of diseases involving mitochondrial dysfunction.”

Professor Jane Farrar from Trinity’s School of Genetics and Microbiology said, “We are very excited by the prospect of this new gene therapy strategy, although it is essential to highlight that there is still a long journey to complete from a research and development perspective before this therapeutic approach may one day be available as a treatment.”

“OPA1 mutations are involved in DOA, and so this OPA1-based therapeutic approach is relevant to DOA. However, mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in many neurological disorders that collectively affect millions of people worldwide. We think there is great potential for this type of therapeutic strategy targeting mitochondrial dysfunction to benefit and thereby make a major societal impact. Having worked together with patients over many years who live with visual and neurological disorders, it would be a privilege to play a role in a treatment that may one day help many.”

The scientists publish their results today [Thursday 26th November 2020] in the leading journal, Frontiers in Neuroscience.