While evaluating the patients’ health, one of the first things a doctor does is measure the patient’s biomedical vital signs, including respiratory rate, body temperature, and heart rate. The technological advancement in infrared thermography (IRT) and signal processing have facilitated measurement of human vital signs, but such techniques are not yet widely applied to marine mammals.

So, how do you measure vital signs when your patient is a huge, endangered Paikea humpback whale?

Well, drones might be the solution! Measuring whale health remains a long-standing challenge for cetacean scientists and conservationists, but advances in drone technology, infrared imaging, and data-processing have created unique opportunities to help whales survive.

A team of international scientists led by the University of Canterbury (UC) has measured those vital signs of a free-swimming great whale using a ‘drone doctor.’

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales are one of the larger rorqual species. The adults range in length from 12-16 m (39-52 ft) and weigh around 25-30 metric tons (28-33 short tons). They feed in polar waters and migrate to their tropical breeding grounds throughout Oceania to give birth and raise their newborn calves.

“For the endangered Paikea humpback whales of Polynesia – a population that was decimated by whaling through the second half of the 20th century and the only endangered migratory humpbacks on the planet today – measuring and monitoring whale health is of paramount importance,” says the research lead and UC environmental geochemist Associate Professor Travis Horton.

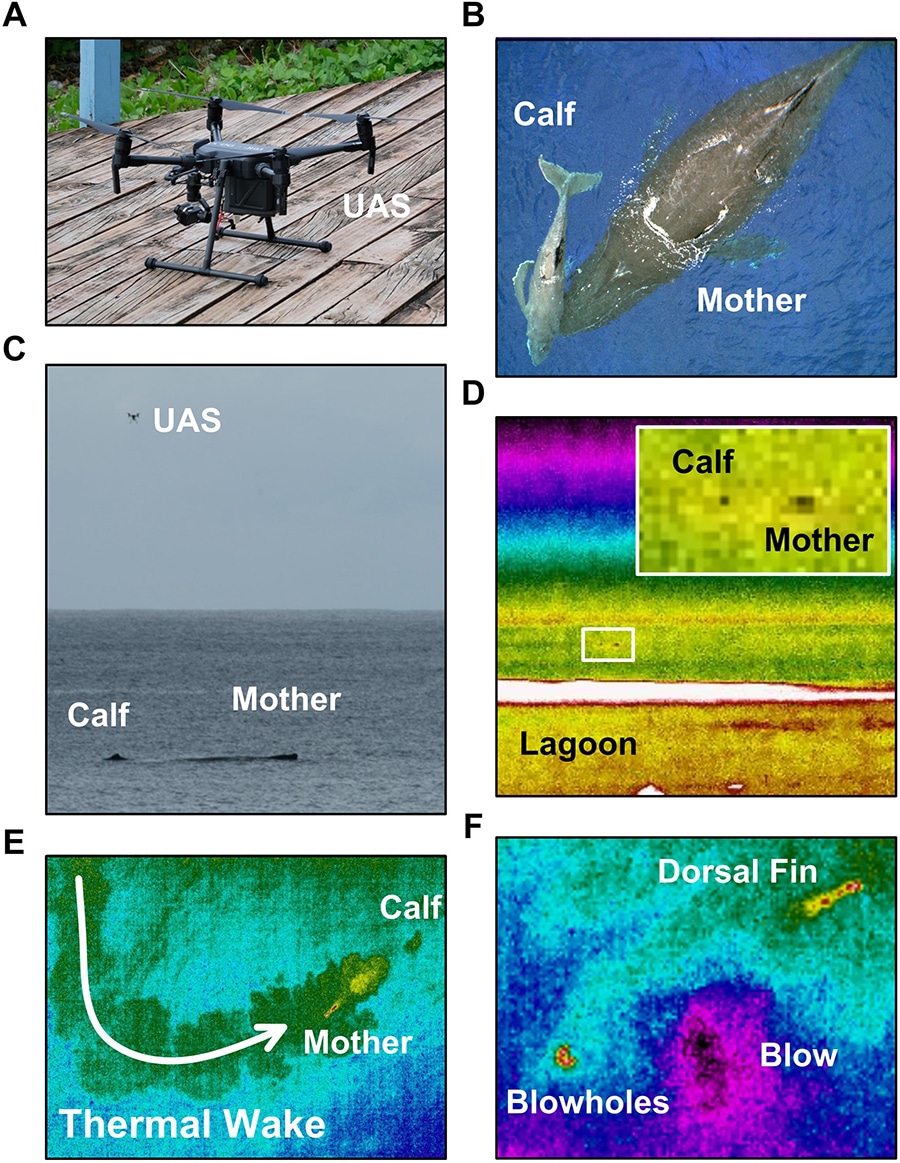

The discovery happened when the team deployed an infrared camera on a quad-copter drone in Rarotonga, Cook Islands, during the 2018 humpback whale calving season. Instead of messing with endangered whales by boat, the scientists stayed onshore and took pictures of the whales from above with the help of drone doctor.

Using non-invasive drones allowed the team to record high-resolution infrared videos of a mother whale resting at the ocean’s surface over a period of three hours. The resulting infrared data-enabled the measurement of body temperature, breathing rate, and heart rate based on changes in skin temperature at the blowholes and major arteries present in the dorsal fin.

“The key outcome from this multi-disciplinary research is the creation of a non-invasive method for measuring marine mammal vital signs and health,” Associate Professor Horton says.

“In addition to helping South Pacific nations better understand endangered Paikea humpback whales, the research also establishes a novel technological platform for measuring the biomedical condition of cetaceans inhabiting highly utilized marine environments, animals tangled in fishing lines, and live-stranded whales.”

Despite its novel results, published in Frontiers in Marine Science, there remain several key limitations to unoccupied aerial systems (UAS) and infrared thermography (IRT), including its sensitivity to environmental conditions and animal behavior; equipment costs and associated risks; potential regulatory restrictions; time-intensive nature of IR data processing; factors that can impact data quality, such as imaging angle and sensor accuracy.