Methane seeps a location where methane gas escapes from an underground reservoir and into the ocean. Methane seeps have been found all through the world’s oceans.

A recently discovered methane seep in the Ross Sea is the first active seep found in Antarctica. This discovery offers a new understanding of the methane cycle and the role methane found in this region may play in warming the planet.

Andrew Thurber, a marine ecologist at Oregon State University, said, “Methane is the second-most effective gas at warming our atmosphere and the Antarctic has vast reservoirs that are likely to open up as ice sheets retreat due to climate change. This is a significant discovery that can help fill a large hole in our understanding of the methane cycle.”

Scientists discovered that microbes around the Antarctic seep are slightly different than those found elsewhere. This helps scientists in understanding methane cycles as well as the factors that determine whether methane will reach the atmosphere and contribute to further warming.

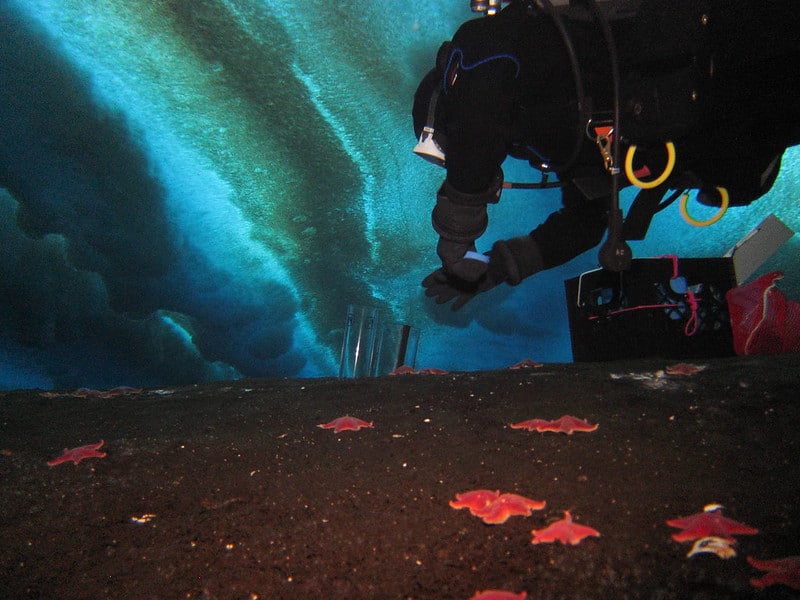

Thurber said, “An expansive microbial mat, about 70 meters long by a meter across, seafloor the sea floor about 10 meters below the frozen ocean surface. These mats, which are produced by bacteria that exist in a symbiotic relationship with methane consumers, are a telltale indication of the presence of a seep.”

“The microbial mat is the road sign that there’s a methane seep here. We don’t know what caused these seeps to turn on. We needed some dumb luck to find an active one, and we got it.”

Scientists studied the site for five years to see how microbes respond to the formation of a seep. The interesting fact was the microbial community did not develop as previously predicted based on other methane seeps we have studied around the globe.

It was assumed that microbes should respond quickly to changes in the environment, but that wasn’t reflected in what OSU’s team saw in Antarctica.

Thurber said, “To add to the mystery of the Antarctic seeps, the microbes we found were the ones we least expected to see at this location. There may be a succession pattern for microbes, with certain groups arriving first and those that are most effective at eating methane arriving later.”

“We’ve never had the opportunity to study a seep as its forming or one in Antarctica, because of this discovery we can now uncover whether seeps just function differently in Antarctica or whether it may take years for the microbial communities to become adapted.”

“It is important to understand how methane seeps behave in this environment so researchers can begin factoring those differences into climate change models.”

Journal Reference:

- Andrew R. Thurber et al. Riddles in the cold: Antarctic endemism and microbial succession impact methane cycling in the Southern Ocean. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2020.1134