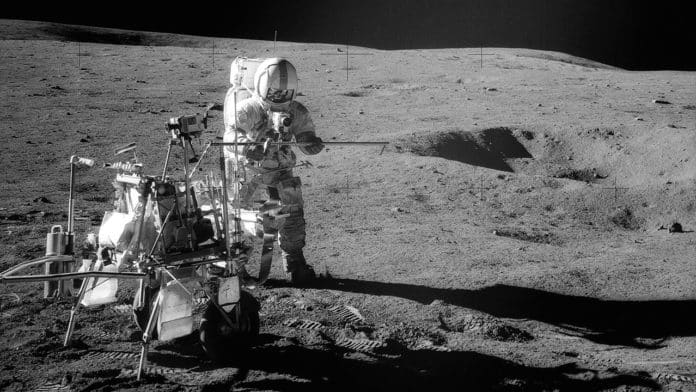

Scientists may have just found the oldest intact Earth rock—on the moon. Scientists have discovered the rock decades ago by the Apollo 14 crew.

The Apollo missions brought back a whole lot of rock samples, and scientists have been methodically analyzing them ever since. This one seems to have been somewhere near the end of the list, but it may be the most interesting one ever found.

An international team of scientists associated with the Center for Lunar Science and Exploration (CLSE), part of NASA’s Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute, found evidence that the rock was launched from Earth by a large impacting asteroid or comet.

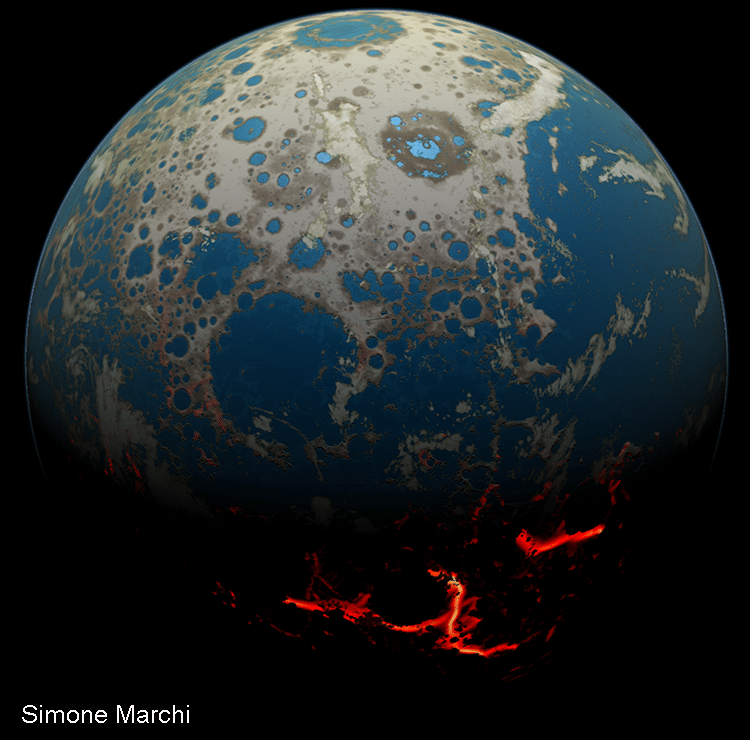

This impact jettisoned material through Earth’s primitive atmosphere, into space, where it slammed into the outside of the Moon (which was three times nearer to Earth than it is presently) around 4 billion years back. The stone was along these lines blended with other lunar surface materials into one example.

The group created systems for finding impactor parts in the lunar regolith, which incited CLSE Principal Investigator Dr. David A. Kring, a Universities Space Research Association (USRA) scientists at the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI), to provoke them to find a bit of Earth on the Moon.

Dr. Kring said, “It is an extraordinary find that helps paint a better picture of early Earth and the bombardment that modified our planet during the dawn of life.”

It is conceivable that the example isn’t of the terrestrial source, yet rather crystallized on the Moon, nonetheless, that would require conditions at no other time gathered from lunar examples. It would require the example to have framed at huge profundities, in the lunar mantle, where altogether different rock pieces are anticipated. Along these lines, the least complex elucidation is that the example originated from Earth.

The rock crystallized about 20 kilometers beneath Earth’s surface 4.0-4.1 billion years ago. It was then excavated by one or more large impact events and launched into cislunar space. Previous work by the team showed that impacting asteroids at that time were producing craters thousands of kilometers in diameter on Earth, sufficiently large to bring material from those depths to the surface.

Once the sample reached the lunar surface, it was affected by several other impact events, one of which partially melted it 3.9 billion years ago, and which probably buried it beneath the surface. The sample is, therefore, a relic of an intense period of bombardment that shaped the solar system during the first billion years. After that period, the Moon was affected by smaller and less frequent impact events.

The final impact event to affect this sample occurred about 26 million years ago, when an impacting asteroid hit the Moon, producing the small 340 meter-diameter Cone Crater, and excavating the sample back onto the lunar surface where astronauts collected it almost exactly 48 years ago (January 31–February 6, 1971).

Kring noted, “The conclusion of a terrestrial origin for the rock fragment will be controversial. While the Hadean Earth is a reasonable source for the sample, the first find of this kind may be a challenge for the geologic community to digest.”

“The samples of Hadean Earth certainly peppered the lunar surface; other samples will likely be found with additional study.”

Dr. Katharine Robinson, a postdoctoral researcher at the LPI, was also involved in the study, as were Dr. Marion Grange (Curtin University), Dr. Gareth Collins (Imperial College London), Dr. Martin Whitehouse (Swedish Museum of Natural History), Dr. Josh Snape (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam), and Prof. Marc Norman (Australian National University).