Earth’s inner core is the innermost geologic layer of the Earth. It is primarily a solid ball with a radius of about 1,220 kilometers (760 miles), which is about 20% of the Earth’s radius or 70% of the Moon’s radius.

Understanding the Earth’s core could help scientists better understand forces that affect the entire planet.

In a new study, scientists made seismic observations and shown that the Earth’s inner core is hot, under immense pressure, and snow-capped.

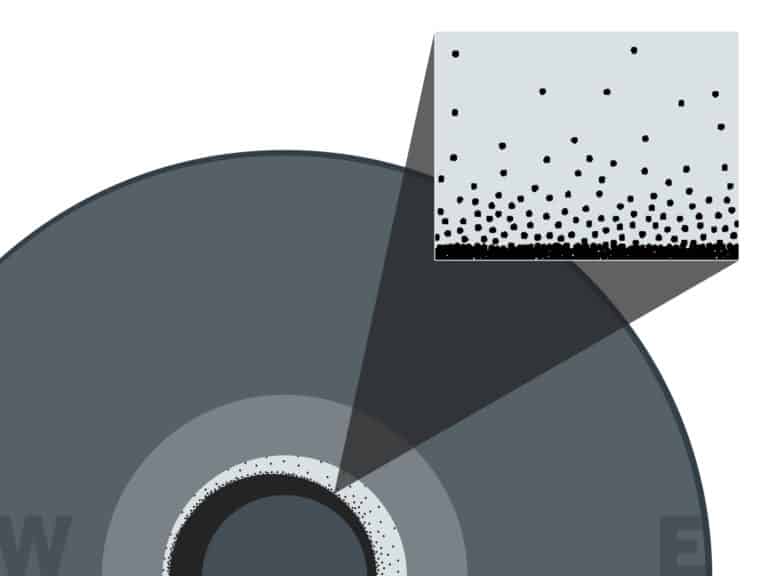

The snow is made of small particles of iron—a lot heavier than any snowflake on Earth’s surface—that fall from the molten outer ore and heap over the inner core, making piles up to 200 miles thick that cover the inner core.

Jung-Fu Lin, a professor in the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin, said, “The Earth’s metallic core works like a magma chamber that we know better of in the crust.”

As the Earth’s core can’t be sampled, thus scientists choose to examine it by recording and analyzing signals from seismic waves as they pass through the Earth. They found that the Iron snow could cover the core, and this snow-capped core is responsible for the aberrations between recent seismic wave data and the values that would be expected based on the current model of the Earth’s core have raised questions.

In 1960, scientist S.I. Braginkskii proposed that there is a slurry layer present between the inner and outer core. However, prevailing knowledge about heat and pressure conditions in the core condition suppressed that hypothesis.

This new study on core-like materials found that crystallization was possible and that about 15% of the lowermost outer core could be made of iron-based crystals that eventually fall down the liquid outer core and settle on top of the solid inner core.

Nick Dygert, an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee, aid, “It’s a bizarre thing to think about. You have crystals within the outer core snowing down onto the inner core over a distance of several hundred kilometers.”

Scientists noted, “the accumulated snowpack as the cause of the seismic aberrations. The slurry-like composition slows the seismic waves. The variation in snow pile size—thinner in the eastern hemisphere and thicker in the western—explains the change in speed.”

Youjun Zhang, an associate professor at Sichuan University in China, led the study said, “The inner-core boundary is not a simple and smooth surface, which may affect the thermal conduction and the convections of the core.”

For the study, scientists compared the snowing of iron particles with a process that happens inside magma chambers closer to the Earth’s surface. In magma chambers, the compaction of the minerals creates what’s known as ‘cumulate rock,’ whereas, in Earth’s core, the compaction of the iron contributes to the growth of the inner core and shrinking of the outer core.

Bruce Buffet, a geosciences professor at the University of California, Berkley who studies planet interiors and who was not involved in the study, said, “the research confronts longstanding questions about the Earth’s interior and could even help reveal more about how the Earth’s core came to be.”

“Relating the model predictions to the anomalous observations allows us to draw inferences about the possible compositions of the liquid core and maybe connect this information to the conditions that prevailed at the time the planet was formed. The starting condition is an important factor in Earth becoming the planet we know.”

The study is available online and will be published in the print edition of the journal JGR Solid Earth on December 23.