How long was a day on Earth? Or, more specifically, how long did it take for the Earth to turn once on its axis?

24 hours?

Wrong! According to a new study, days were half-hour shorter 70 million years ago. This suggests a day lasted only 23 and a half hours.

Meanwhile, Earth turned faster at the end of the time of the dinosaurs than it does today, rotating 372 times a year, compared to the current 365.

Scientists examined growth things of the mollusk shells using lasers and count the growth rings more accurately. Using lasers, they sampled minute slices of the shell.

Trace elements in these tiny samples reveal information about the temperature and chemistry of the water at the time the shell formed.

Determining growth rings allowed scientists to determine the number of days in a year and more accurately calculate the length of a day 70 million years ago.

Also, the measurement informs models regarding how the Moon formed and how close Earth it has been over the 4.5-billion-year history of the Earth-Moon gravitational dance.

Niels de Winter, an analytical geochemist at Vrije Universiteit Brussel and the lead author of the new study, said, “We have about four to five data points per day, and this is something that you rarely get in geological history. We can look at a day 70 million years ago. It’s pretty amazing.”

“Chemical analysis of the shell indicates ocean temperatures were warmer in the Late Cretaceous than previously appreciated, reaching 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) in summer and exceeding 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) in winter. The high summer temperatures likely approached the physiological limits for mollusks.”

Peter Skelton, a retired lecturer of palaeobiology at The Open University and a rudist expert unaffiliated with the new study, said, “The high fidelity of this data-set has allowed the authors to draw two particularly interesting inferences that help to sharpen our understanding of both Cretaceous astrochronology and rudist palaeobiology.”

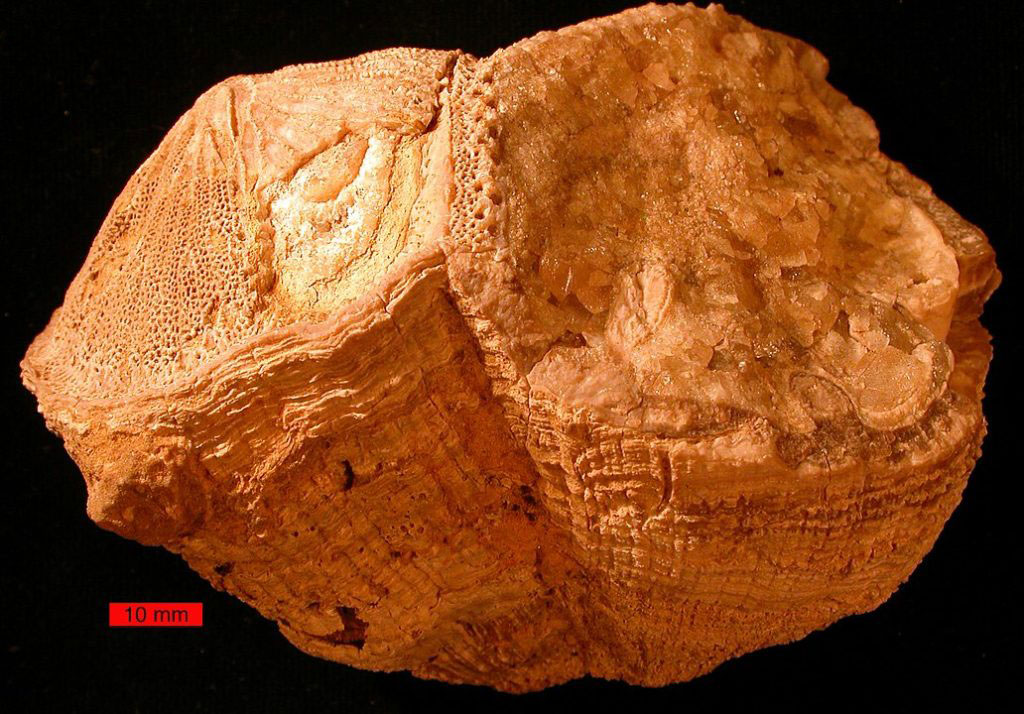

For the study, scientists mainly analyzed Torreites sanchezi mollusks that look like tall pint glasses with lids shaped like bear claw pastries. The mollusks lived for over nine years in a shallow seabed in the tropics—a location which is now 70-million-years later, dry land in the mountains of Oman.

de Winter said, “Rudists like Torreites sanchezi mollusks are quite special bivalves. There’s nothing like it living today. In the late Cretaceous especially, worldwide, most of the reef builders are these bivalves. So they took on the ecosystem building role that the corals have nowadays.”

Scientists used seasonal variations in the fossilized shell to recognize years. The investigation uncovered that the composition of the shell changed more through the span of a day than over seasons, or with the cycles of ocean tides. The fine-scale resolution of the daily layers shows the shell grew a lot quicker during the day than at night.

This result suggests daylight was more critical to the lifestyle of the ancient mollusk than might be expected if it fed itself primarily by filtering food from the water, like modern-day clams and oysters.

Skelton said, “Until now, all published arguments for photosymbiosis in rudists have been essentially speculative, based on merely suggestive morphological traits, and in some cases were demonstrably erroneous. This paper is the first to provide convincing evidence in favor of the hypothesis, but cautioned that the new study’s conclusion was specific to Torreites and could not be generalized to other rudists.”

The analysis also revealed a careful count of the number of daily layers found 372 for each yearly interval. However, it is not surprising as scientists know days were shorter in the past. The result is precise now available for the late Cretaceous and could be used to model the evolution of the Earth-Moon system.

The study is published in AGU’s journal Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology.