Sometimes we mimic other’s expressions and try to reflect their emotions. But do we interpret them correctly? And do we trust our own judgment?

UNIGE scientists are now testing how confident we feel when judging other people’s emotions. They are also testing for what areas of the brain are used while doing this activity.

Our day by day choices accompany a level of confidence, yet confidence doesn’t generally run connected at the hip with decision’s precision.

We are some of the time wrong notwithstanding when we are totally confident about having taken the correct decision– as, for example, when making a poor investment in the stock market. The equivalent goes for our social collaborations: we are continually translating the demeanors on the essences of everyone around us, and the conviction we have in our own understandings is central.

Indrit Bègue, a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Psychiatry in UNIGE’s Faculty of Medicine said, “Take the case of Trayvon Martin in the US, which is a perfect illustration of this. Trayvon was a 17-year-old African-American teenager who was shot dead by George Zimmerman, despite being unarmed. Zimmerman thought the young boy “looked suspicious”, an altercation broke out with the fatal outcome that we’re all familiar with.”

“But, why was Zimmerman so sure that Martin “looked suspicious” and thus, was dangerous, when all he was actually doing was waiting in front of his father’s house?”

“Through this study, we are trying answer this type of question to test the level of confidence we have in our interpretations of the emotional behavior of others, and to discover which areas of the brain are activated during these interpretations.”

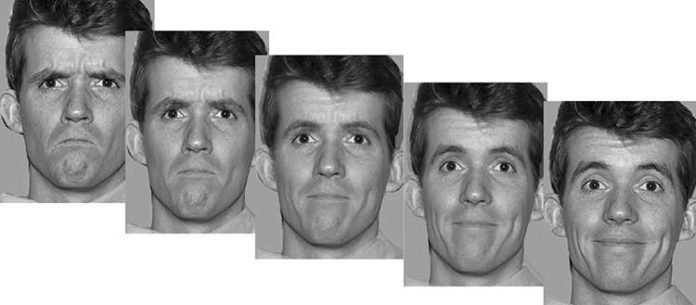

Scientists measured confidence-related behavior by asking 34 participants to judge emotional faces displaying a mix of happy and angry emotions, with each face being framed by two horizontal bars of varying thickness. Some of the faces were very clearly happy or angry, while others were highly ambiguous. The participants first had to define what emotion was represented on each of the 128 faces that flashed up.

Scientists then chose which of the two bars was thicker. Finally, for every decision they made, participants had to indicate their level of confidence in their choice on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all sure) to 6 (certain).

Patrik Vuilleumier, a professor in UNIGE’s Department of fundamental neurosciences said, “The bars were used to evaluate their confidence in visual perception, which has already been studied in depth. Here it served as a control mechanism.”

Indrit said, “The results of the tests surprised us. Strikingly, the average level of confidence in emotional recognition was higher (5.88 points) than for visual perception (4.95 points), even though participants made more errors in emotional recognition (79 % correct answers) than with the lines (82% correct answers)!”

The study explained, “Learning emotional recognition is not as easy as for perception: our interlocutors may be ironic, lying or prevented from expressing their facial emotions due to social conventions – if their boss is present, for instance. It follows that it is more difficult to correctly calibrate our confidence in recognizing other people’s emotions in the absence of any feedback.”

“In addition, we have to interpret an expression very quickly because it is fleeting. So, we feel that our first impression is the right one, and trust our judgment about an angry face or mouth. On the other hand, judging perception may be more attentive and benefits from direct feedback about its accuracy. If there is hesitation, confidence is lower than for emotions, because we know that we can easily be wrong and be contradicted.”

As the brain correlates, scientists analyzed the neural mechanisms amid this procedure of certainty on one’s emotional recognition by giving members a practical MRI.

Professor Vuilleumier said, “When the participants judged the lines, the perception (visual areas) and attention (frontal areas) zones were activated. But when assessing confidence in recognizing emotions, areas linked to autobiographical and contextual memory lit up, such as the parahippocampal gyrus and the retrosplenial/posterior cingulate cortex.”

The study demonstrates that brain systems storing personal and contextual memories are directly involved in beliefs on emotional recognition and that they determine the accuracy of the interpretation of facial expressions and the trust placed in them.

Indrit said, “The fact that past experiences are so fundamental to govern our confidence may cause problems in our day-to-day life, because they can skew our judgment, as happened in the Trayvon Martin case, when Zimmerman didn’t see just an impatient young man waiting outside his home, but an angry black man lurking in front of a house. That’s why it’s crucial to give feedback about our emotions early on, so we can teach children to interpret them correctly.”

These results are published in the journal Social, Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.