Black holes are among the strangest things in the universe. They are massive objects – collections of mass – with gravity so strong that nothing can escape, not even light.

When two black holes collide and merge, they produce one of the most catastrophic events in the universe. Just within a second, it releases tremendous amounts of energy as it settles to its final state. This phenomenon gives astronomers a unique chance to observe rapidly changing black holes and explore gravity in its most extreme form.

However, colliding black holes do not produce light. Astronomers can observe the detected gravitational waves they create—ripples in the fabric of space and time.

According to astronomers, the remnant black hole’s behavior is key to understanding gravity and should be encoded in the emitted gravitational waves.

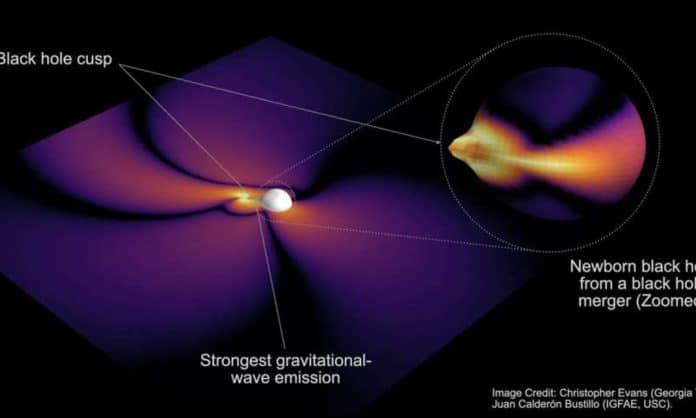

A team of gravitational wave scientists led by the ARC Center of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav) report that when two black holes collide and merge, the remnant black hole “chirps” not once, but multiple times, emanating gravitational waves—intense ripples in the fabric space —that uncover information about its shape.

In the study, scientists explained how gravitational waves encode the shape of merging black holes as they settle into their final form.

Scientists performed simulations of black-hole collisions using supercomputers. They then compared the rapidly changing shape of the remnant black hole to the gravitational waves it emits.

Graduate student and co-author Christopher Evans from the Georgia Institute of Technology (U.S.) says, “We discovered that these signals are far more rich and complex than commonly thought, allowing us to learn more about the vastly changing shape of the final black hole.”

Prof. Calderón Bustillo says, “The gravitational waves from colliding black holes are simple signals known as “chirps.” As the two black holes approach each other, they emit a signal of increasing frequency and amplitude that indicates the orbit’s speed and radius. The pitch and amplitude of the signal increases as the two black holes approach faster and faster. After the collision, the final remnant black hole emits a signal with a constant pitch and decaying amplitude—like the sound of a bell being struck.”

This study demonstrates something completely different happens if the collision is observed from the “equator” of the final black hole.

Prof. Calderón Bustillo said, “When we observed black holes from their equator, we found that the final black hole emits a more complex signal, with a pitch that goes up and down a few times before it dies. In other words, the black hole chirps several times.”

“We discovered that this is related to the shape of the final black hole, which acts like a kind of gravitational-wave lighthouse: When the two original parent black holes are of different sizes, the final black hole initially looks like a chestnut, with a cusp on one side and a wider, smoother back on the other.”

“It turns out that the black hole emits more intense gravitational waves through its most curved regions, which are those surrounding its cusp. This is because the remnant black hole is also spinning and its cusp, and backside repeatedly point to all observers, producing multiple chirps.”

Co-author Prof. Pablo Laguna, former chair of the School of Physics at Georgia Tech and now a professor at the University of Texas at Austin, said, “While a relation between the gravitational waves and the behavior of the final black hole has been long conjectured, our study provides the first explicit example of this kind of relation.”

Journal Reference:

- Calderon Bustillo, J., Evans, C., Clark, J.A. et al. Post-merger chirps from binary black holes as probes of the final black-hole horizon. Commun Phys 3, 176 (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s42005-020-00446-7