Traveling to faraway places is a great way to have new experiences. But sometimes, when you cross a long way, you might feel tired, need help sleeping, and face other problems. This is called jet lag, which can make your exciting adventure less fun.

Jet lag happens because our body has an internal clock that tells us when to sleep and be awake. When we go to places with a different time zone, our body clock gets confused, and that’s when we get jet lag. This can happen more as we get older.

Researchers from Northwestern University and the Santa Fe Institute studied how our body’s internal clocks work together and how aging and things like jet lag can mess them up. They used a special model to understand this better.

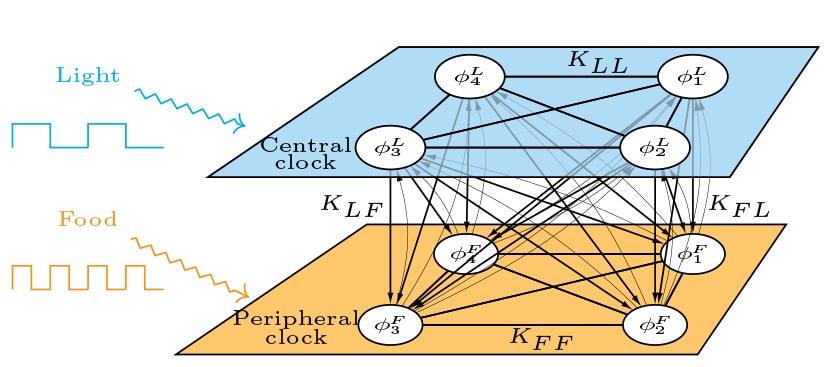

Recent studies have revealed that circadian clocks exist in nearly every cell and tissue within our body. These clocks don’t all work the same way; they rely on different signals to stay on track. For example, the clock in our brain uses sunlight as a guide, while the clocks in our body’s organs follow the timing of our meals.

Author Yitong Huang said, “Conflicting signals, such as warm weather during a short photoperiod or nighttime eating -eating when your brain is about to rest — can confuse internal clocks and cause desynchrony.”

Right now, we don’t know much about how the different internal clocks in our bodies affect each other. It’s tricky because there are many clocks, so researchers usually use simple models to study them.

But Huang and her team did something different. They made a math model that’s more like the real thing. It has two groups of oscillators that act like our body’s clocks. These clocks affect each other and listen to their special cues from the outside world.

The researchers used their model to see how our body’s clocks can get messed up and what makes it worse. They found that as we get older, our body’s clocks don’t talk to each other or respond to light as much, making us more vulnerable to disruptions and slower to get back on track.

But they also discovered a way to beat jet lag and sleep better: eat a big meal in the morning in the new time zone. They said “it’s not a good idea to keep changing your meal times or eating at night because it can mess up your body’s clocks.”

Next, they want to find out how to make our body’s clocks stronger. This helps avoid jet lag in the first place and stay healthy as we get older.

Learning how the body’s internal clocks work together and how they respond to aging and problems like jet lag is an excellent way to make ourselves healthier. If this can make body clocks tick together and do healthy things. This can reduce the problems of jet lag and getting older. This means we can have better trips and stay healthy as we age.

Journal reference:

- Yitong Huang, Yuan Zhao Zhang, et al., A minimal model of peripheral clocks reveals differential circadian re-entrainment in aging. Chaos. DOI: 10.1063/5.0157524.