Circadian rhythms govern diverse aspects of physiology, including sleep/wake cycles, cognition, gene expression, temperature regulation, and endocrine signaling. Similarly, studies of brain function in both humans and animals have documented time of day–dependent variation at multiple scales of brain organization.

Despite the clear influence of circadian rhythms on physiology, most studies of brain function do not report or consider the impact of time of day on their findings.

A new study suggests that the strength of the brain’s global signal fluctuation shows an unexpected decrease as the day progresses.

Scientists analyzed functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data of approximately 900 subjects who were scanned between 8 am and 10 pm on two different days as part of the Human Connectome Project.

Various investigations have indicated that the brain’s global signal changes more unequivocally when one is drowsy (for example, after inadequate rest) and changes less when one is progressively alert (for example, after espresso).

Based on known circadian variation in sleepiness, the authors speculated that global signal fluctuation would be lowest in the morning, increment in the mid-afternoon, and dip in the early evening.

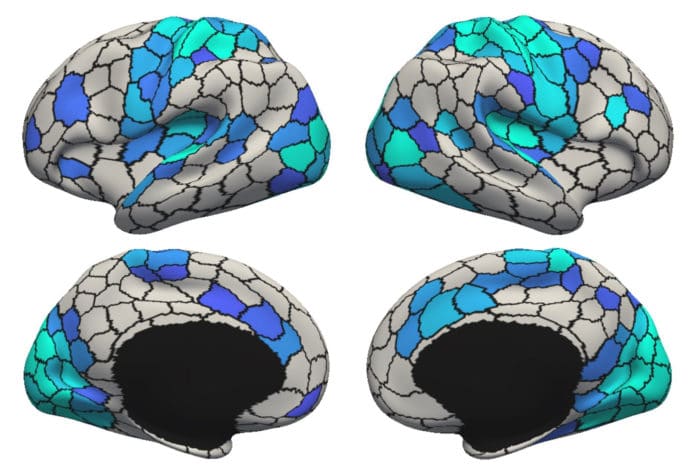

Instead, they observed a combined decline in global signal fluctuation as the day progressed. This global decline was generally conspicuous in visual and somatosensory brain regions, which are known for communicating dynamic fluctuations inside people after some time.

Over the entire mind, time of day was additionally connected with marked diminishes in resting-state functional connectivity—the associated action between various brain regions when no specific task is being performed.

Csaba Orban, the first author of the study, said, “We were surprised by the size of the overall time-of-day effects since the global fMRI signal is affected by many factors and there is substantial variation across individuals. At the present moment, we don’t have a good explanation of the directionality of our findings. However, the fact that we also observed slight time-of-day-associated variation in the breathing patterns of participants suggests that we may also need to consider clues outside of the brain to understand these effects fully.”

Based on the study, scientists suggest that time of day of fMRI scans and other experimental protocols and measurements, as this could help account for between-study variation in results and potentially even failure to replicate findings.

Thomas Yeo, the study’s senior author, said, “We hope these findings will motivate fellow neuroscientists to give more consideration to potential effects of time of day on measures of brain activity, especially in other large-scale studies where subjects are often scanned throughout the day for logistical reasons.”

The study is published in the journal PLOS Biology.