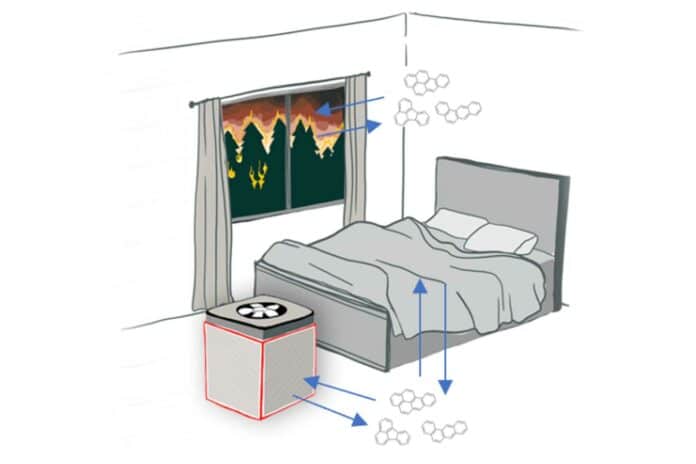

After a campfire, the smoky smell might be an excellent memory, but after a wildfire, it poses health risks. Wildfire smoke lingers longer in homes and businesses than campfire smoke. Wildfires generate toxic compounds known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), produced during high-temperature combustion processes.

A recent study led by an associate professor in Mechanical and Materials Engineering- Elliott Gall- investigated the duration of harmful chemicals from wildfire smoke and identified the most efficient household cleaners to eliminate them. Scientists report the magnitude and persistence of select surface-associated PAHs on three common indoor materials: glass, cotton, and mechanical air filter media.

Gall said, “They are associated with a wide variety of long-term adverse health consequences like cancer, potential complications in pregnancy, and lung disease. So, if these compounds are depositing or sticking onto surfaces, people should be aware of different exposure routes. By now, most people in Portland are probably thinking about how to clean their air during a wildfire smoke event, but they might not be thinking about other routes of exposure after the air clears.”

Preliminary findings indicate that PAH levels persist at elevated levels for weeks after exposure to wildfire smoke. Reductions of 74%, 81%, and 88% in PAHs on air filters, cotton, and glass, respectively, took 37 days. While this reduction is significant, it entails prolonged health risks due to extended exposure.

However, washing smoke-exposed cotton once decreased PAHs by 80%, and using a commercial glass cleaner on glass materials reduced PAHs by 60% to 70%. Unlike glass and cotton, air filters cannot be cleaned and must be replaced after intense smoke exposure.

Gall said, “Even if there’s potentially some more life in them, PAHs can partition off the filter over time and be emitted back into your space. While it may be a slow process, our study shows partitioning of PAHs from filters and other materials loaded with smoke may result in concentrations of concern in air.”

“And while that partitioning is occurring, dermal contact and ingestion of PAHs from the materials may be important. One example might be holding and drinking from a glass exposed to wildfire smoke.”

“It was important to consider the effect of cleaning solutions available to the average person. However, the findings also open the door to additional questions. How do materials like drywall or ceramic respond to cleaning, for example? What if an individual has access to a washer but not a dryer? Would PAHs still be reduced to non-toxic levels?”

Journal Reference:

- Aurélie Laguerre and Elliott T. Gall. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Wildfire Smoke Accumulate on Indoor Materials and Create Postsmoke Event Exposure Pathways. Environmental Science and Technology. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.3c05547