Recently made study at MIT and Dartmouth College uncovered the impact of an additional kind of land harnessing and exorbitant agriculture on regional climate. Researchers are now greenhouse gas emissions but also an alteration in land utilization such as deforestation are a considerable key to the world’s climate system.

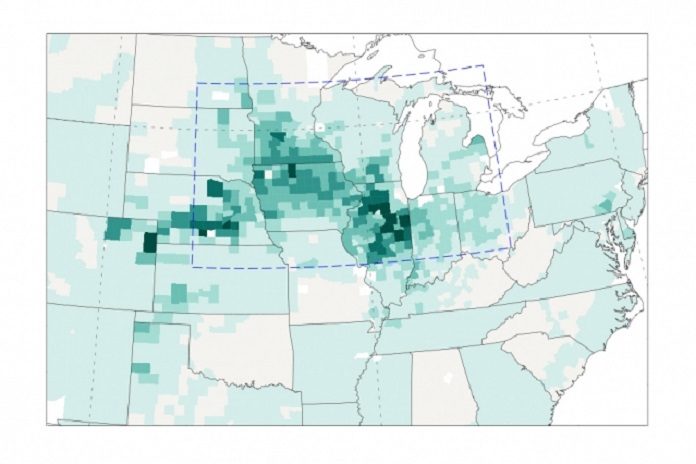

A study demonstrates that in the last half of the 20th century, the midwestern U.S. went through an intensification of agricultural practices that led to a substantial rise in production of corn and soybeans. Besides, over the same period in that region, summers were exceptionally cooler and had greater rainfall than during the antecedent half-century.

This impact, with regional cooling in a time of overall global warming, may have masked part of the warming effect that would have found over that period, and the recent discoveries could help to refine global climate models by consolidating such regional impacts.

Courtesy of researchers

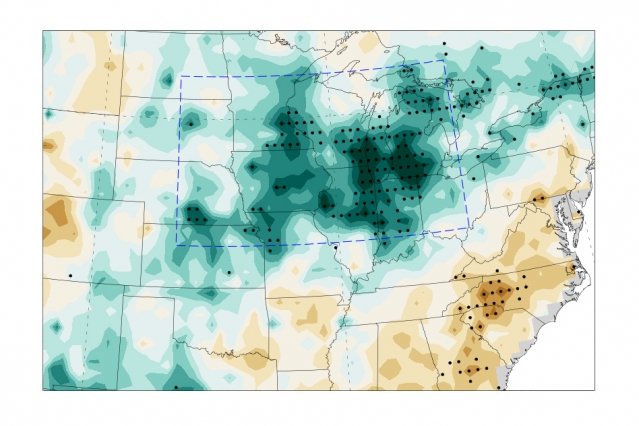

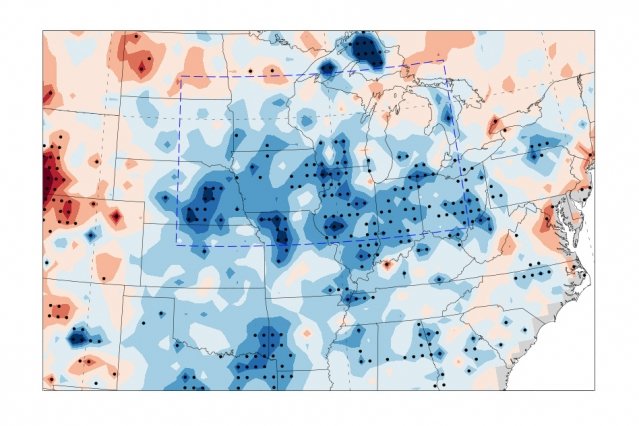

The group of scientists discovered that there was a swingeing tie-in, in both space and time, amid the intensification of agriculture in the Midwest, the fall in found average daytime temperatures in the summer, and rise in the local rainfall.

In addition to this circumstantial evidence, they recognized a mechanism that elaborates the relation, suggesting that there was indeed a cause-and-effect link between the changes in vegetation and the climatic impacts.

Elfatih Eltahir, the Breene M. Kerr Professor of Hydrology and Climate, explains that plants “breathe” in the carbon dioxide they need for photosynthesis by opening modest pores, called stoma, but every time they do this they likewise lose moisture to the atmosphere.

With the amalgamation of improved seeds, fertilizers, and other practices, between 1950 and 2009 the annual yield of corn in the Midwest raised about fourfold and that of soybeans twofold. These changes were related to denser plants with more leaf mass, which thus raised the quantity of moisture discharged into the atmosphere. That extra moisture served to both cool the air and raise the amount of rainfall.

Eltahir said, “For some time, we’ve been interested in how changes in land use can influence climate.”

Courtesy of researchers

“It’s an independent problem from carbon dioxide emissions” which have been more intensively studied.”

Eltahir, Alter, and their co-authors suggested that data which demonstrated, over the course of the 20th century, and Eltahir mentioned, “There were substantial changes in regional patterns of temperature and rainfall. A region in the Midwest got colder, which was a surprise.”

“Because weather records in the U.S are quite extensive, there is a robust dataset that shows significant changes in temperature and precipitation in the region.”

He added, over the last half of the century, average summertime rainfall increased by about 15 percent compared to the previous half-century, and average summer temperatures decreased by about half a degree Celsius. The effects are “significant, but small.”

Post presenting it into a regional U.S. climate model a factor to account for the more intensive agriculture that has made the Midwest one of the world’s most productive agricultural areas.

The researchers found, “the models show a small increase in precipitation, a drop in temperature, and an increase in atmospheric humidity.”

Eltahir says, exactly what the climate records actually show.

He said, “That distinctive “fingerprint,” strongly suggests a causative association. During the 20th century, the midwestern U.S. experienced regional climate change that’s more consistent with what we’d expect from land-use changes as opposed to other forcings.”

Eltahir stresses, this finding in no way contradicts the overall pattern of global warming. But in order to refine the models and improve the accuracy of climate predictions, “we need to understand some of these regional and local processes taking place in the background.”

Unlike land-use changes such as deforestation, which can reduce the absorption of carbon dioxide by trees that can assist to ameliorate discharge of the gas, the changes, in this case, did not reflect any exceptional rise in the area under cultivation, but rather a dramatic increase in yields from existing farmland.

Alter explained, “The area of crops did not expand by a whole lot over that time, but crop production increased substantially, leading to large increases in crop yield.”

Eltahir says the results suggest the possibility that at least on a small-scale regional or local level, intensification of agriculture on existing farmland could be a way of doing some local geoengineering to at least slightly lessen the impacts of global warming. A recent paper from another group in Switzerland suggests just that.

He added, but the results could also portend some unassertive impacts since the kind of intensification of agricultural yields acquired in the Midwest are unlikely to be repeated, and some of the global warming’s effects may “have been masked by these regional or local effects. But this was a 20th-century phenomenon, and we don’t expect anything similar in the 21st century.” So warming in that region in the future “will not have the benefit of these regional moderators.”

Roger Pielke Sr., a senior research scientist at CIRES, at the University of Colorado at Boulder, who was not involved in this work said, “This is a really important, excellent study.”

“The leadership of the climate science community has not yet accepted that human land management is at least as important on regional and local climate as the addition of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere by human activities.”

The results will be published current week in Geophysical Research Letters, in a paper by Ross Alter, a recent MIT postdoc; Elfatih Eltahir, the Breene M. Kerr Professor of Hydrology and Climate; and two others.