Every 11 years or so, the Sun’s magnetic field completely flips. This means that the Sun’s north and south poles switch places. Then it takes about another 11 years for the Sun’s north and south poles to flip back again.

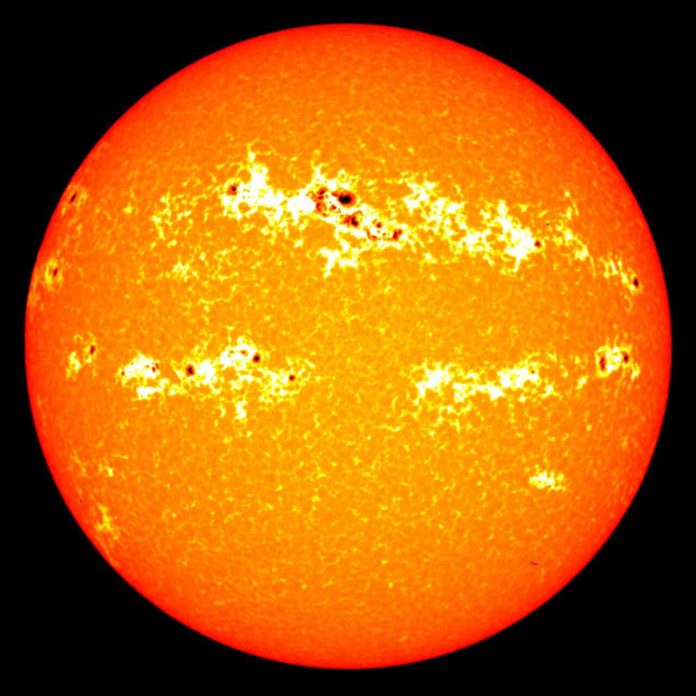

The solar cycle affects activity on the surface of the Sun, such as sunspots which are caused by the Sun’s magnetic fields. Until now, various theories have tracked sunspots but are unable to explain why the number of spots peaks every 11 years.

In an effort to understand it, scientists at the University of Washington have proposed a model of plasma motion to explain the 11-year sunspot cycle and several other previously mysterious properties of the Sun.

Scientists created this model by relying on their previous work with fusion energy research. The model demonstrates that a slight layer underneath the Sun’s surface is key to many highlights we see from Earth, such as sunspots, magnetic reversals, and solar flow.

The fusion reactor uses very high temperatures similar to those inside the Sun to separate hydrogen nuclei from their electrons. In both the Sun and in fusion reactors, the nuclei of two hydrogen atoms fuse, releasing vast amounts of energy.

The type of reactor scientists have focused on is a spheromak that contains the electron plasma within a sphere that causes it to self-organize into specific patterns. When they began to consider the Sun, they observed similarities and created a model for what might be happening in the celestial body.

First author Thomas Jarboe, a UW professor of aeronautics and astronautics, said, “Our model is completely different from a normal picture of the Sun. I think we’re the first people that are telling you the nature and source of solar magnetic phenomena—how the Sun works.”

In the new model, a thin layer of magnetic flux and plasma, or floating electrons, moves at different speeds on a different part of the Sun. The distinction in speed between the flows makes bits of magnetism, known as magnetic helicity, that are similar to what happens in some fusion reactor concepts.

Jarboe said, “Every 11 years, the Sun grows this layer until it’s too big to be stable, and then it sloughs off. Its departure exposes the lower layer of plasma moving in the opposite direction with a flipped magnetic field.”

“When the circuits in both hemispheres are moving at the same speed, more sunspots appear. When the circuits are different speeds, there is less sunspot activity. That mismatch may have happened during the decades of little sunspot activity known as the “Maunder Minimum.”

“If the two hemispheres rotate at different speeds, then the sunspots near the equator won’t match up, and the whole thing will die.”

“Scientists had thought that a sunspot was generated down at 30 percent of the depth of the Sun, and then came up in a twisted rope of plasma that pops out. Instead, his model shows that the sunspots are in the “supergranules” that form within the thin, subsurface layer of plasma that the study calculates to be roughly 100 to 300 miles (150 to 450 kilometers) thick, or a fraction of the Sun’s 430,000-mile radius.”

“The sunspot is an amazing thing. There’s nothing there, and then all of a sudden, you see it in a flash.”

“Other properties explained by the theory include flow inside the Sun, the twisting action that leads to sunspots and the entire magnetic structure of the Sun. The paper is likely to provoke intense discussion.”

“I hope that scientists will look at their data in a new light, and the researchers who worked their whole lives to gather that data will have a new tool to understand what it all means.”

The study describing the model is published in the journal Physics of Plasmas.