Tattoos are used in medicine to cover up scars, guide repeated cancer radiation treatments, bracelets as medical alerts, etc. These tattoos are administered by repeated needle injection that causes pain, bleeding, and risk of infection, which limits more widespread use.

Scientists at the Georgia Institute of Technology have developed low-cost, painless, and bloodless tattoos that can be self-administered. These tattoos have many applications, from medical alerts to tracking neutered animals to cosmetics.

Mark Prausnitz, principal investigator on the paper, said, “We’ve miniaturized the needle so that it’s painless but still effectively deposits tattoo ink in the skin. This could be a way to make medical tattoos more accessible and create new opportunities for cosmetic tattoos because of the ease of administration.”

“We saw this as an opportunity to leverage our work on microneedle technology to make tattoos more accessible. While some people are willing to accept the pain and time required for a tattoo, we thought others might prefer a tattoo pressed onto the skin and does not hurt.”

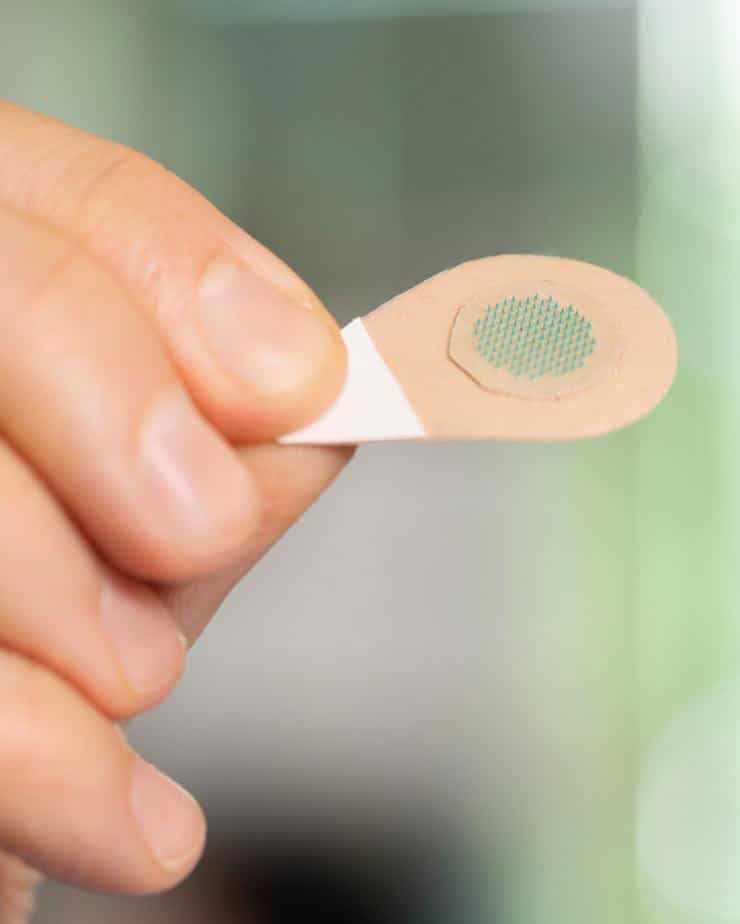

The microneedles that scientists developed are smaller than a grain of sand. They are made of tattoo ink encased in a dissolvable matrix.

Song Li, the lead author of the study, said, “Because the microneedles are made of tattoo ink, they deposit the ink in the skin very efficiently. In this way, the microneedles can be pressed into the skin just once and then dissolve, leaving the ink in the skin after a few minutes without bleeding.”

The scientists begin with a mould that has microneedles in an image-forming pattern. They apply a patch backing to ease handling and fill the tattoo ink-filled microneedles in the mould. The microneedles in the resulting patch disintegrate and release the tattoo ink when it is placed on the skin for a short period of time. The microneedles can accommodate tattoo inks of different colors, including black-light ink, which can only be viewed under an ultraviolet light source.

Prausnitz’s lab has been researching microneedles for vaccine delivery for years and realized they could be equally applicable to tattoos. With support from the Alliance for Contraception in Cats and Dogs, Prausnitz’s team started working on tattoos to identify spayed and neutered pets but then realized the technology could be effective for people, too.

The study showed that the tattoos could last for at least a year and are likely to be permanent, making them viable cosmetic options for people who want an aesthetic tattoo without the risk of infection or the pain associated with traditional tattoos.

Prausnitz said, “The goal isn’t to replace all tattoos, which are often works of beauty created by tattoo artists. Our goal is to create new opportunities for patients, pets, and people who want a painless tattoo that can be easily administered.”

Journal Reference:

- Song Li et al. Microneedle patch tattoos. iScience. DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105014