An international team of researchers from the University of Adelaide analyzed ancient DNA and discovered chromosomal disorders, potentially marking the first known case of Edwards syndrome found in ancient remains.

The team identified six different cases of Down Syndrome. One patient had Edwards syndrome in Spain, Bulgaria, Finland, and Greece 4,500 years ago. They were buried carefully and with unique items, proving they were valued in their communities.

A collaborative study by first author Dr. Adam “Ben” Rohrlach of the University of Adelaide and senior author Dr. Kay Prüfer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology tested DNA from around 10,000 ancient humans for signs of autosomal trisomies, where they might have an extra copy of one of the first 22 chromosomes.

Dr Rohrlach, a statistician from the University of Adelaide’s School of Mathematical Sciences, said, “Using a new statistical model, we screened the DNA extracted from human remains from the Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron Ages up to the mid-1800s. We identified six cases of Down syndrome.

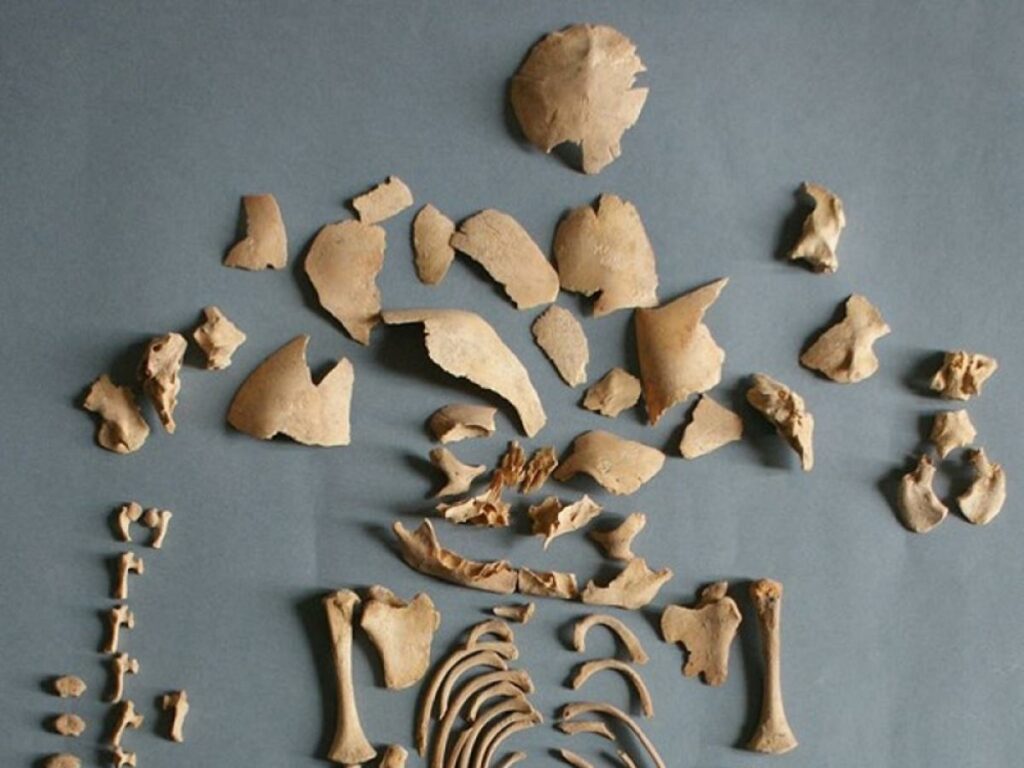

Dr. Rohrlach added, “While we expected that people with Down syndrome certainly existed in the past, this is the first time we’ve been able to reliably detect cases in ancient remains, as they can’t be confidently diagnosed by looking at the skeletal remains alone.”

Down syndrome occurs when an individual has an extra chromosome 21. Researchers found six cases using a new Bayesian approach to check ancient DNA samples accurately and quickly. According to Dr. Adam “Ben” Rohrlach, they discovered something interesting: the only case of Edwards syndrome and more cases of Down syndrome in people from Early Iron Age Spain.

Dr. Patxuka de-Miguel-Ibáñez from the University of Alicante, who led the study on Spanish sites explained, “The method looks for when someone has about 50% too much DNA from one specific chromosome. Then we looked at the skeletons of those with Down syndrome for common bone problems, which could help spot cases in the future when we can’t get ancient DNA.”

The study found a rare condition caused by three copies of chromosome 18. This condition is more severe than Down Syndrome. The remains showed serious problems in Bone formation, and the individual likely died around 40 weeks into gestation. All cases were found in newborn or infant burials but belong to different cultures and periods.

Dr. Rohrlach found that these individuals were buried according to their society’s customs, indicating they were respected community members even in death.

According to Professor Roberto Risch, an archaeologist from The Autonomous University of Barcelona, “It’s unclear why these infants were chosen for special burials, as most people were cremated during this time.”

In conclusion, the study shows that ancient DNA has discovered evidence of Down Syndrome in past human societies. This discovery highlights the lives of individuals with this condition in ancient times, showing they were valued in their communities. Furthermore, researchers identified a rare condition called Edward Syndrome in ancient populations by studying ancient societies’ health and social dynamics.

Journal reference:

- Rohrlach, A.B., Rivollat, M., de-Miguel-Ibáñez, P. et al. Cases of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18 among historic and prehistoric individuals discovered from ancient DNA. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-45438-1.