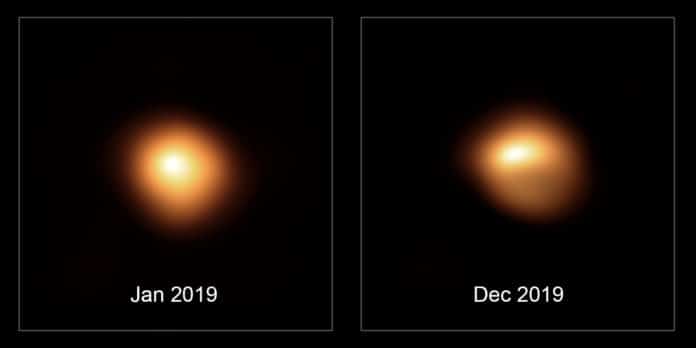

Betelgeuse is a red supergiant star in the constellation of Orion. It has been a beacon in the night sky for stellar observers, but it began to dim late last year, ultimately dropping to around 40% of its usual brightness.

Astronomers are using ESO’s Very Large Telescope to observe the star to understand why it’s becoming fainter.

Many astronomy enthusiasts wondered if Betelgeuse’s dimming meant it was about to explode. Like all red supergiants, Betelgeuse will one day go supernova.

In a new study by the University of Washington, scientists calculated the average surface temperature of the star by using the observations of Betelgeuse taken Feb. 14 at the Flagstaff, Arizona. They found that Betelgeuse is significantly warmer than expected if the recent dimming were caused by a cooling of the star’s surface.

Meanwhile, there is a possibility that the star has disposed of some material from its external layers.

Emily Levesque, a UW associate professor of astronomy, said, “We see this all the time in red supergiants, and it’s a normal part of their life cycle. Red supergiants will occasionally shed material from their surfaces, which will condense around the star as dust. As it cools and dissipates, the dust grains will absorb some of the light heading toward us and block our view.”

Philip Massey, an astronomer with Lowell Observatory, said, “It is still true: Astronomers expect Betelgeuse to explode as a supernova within the next 100,000 years when its core collapses. But the star’s dimming, which began in October, wasn’t necessarily a sign of an imminent supernova.”

It was not simple to measure the temperature of the star. Scientists looked at the spectrum of light emanating from a star and calculated its temperature.

Scientists employed a filter that effectively “dampened” the signal so they could mine the spectrum for a particular signature: the absorbance of light by molecules of titanium oxide.

Levesque said, “Titanium oxide can form and accumulate in the upper layers of large, relatively cool stars like Betelgeuse. It absorbs specific wavelengths of light, leaving telltale “scoops” in the spectrum of red supergiants that scientists can use to determine the star’s surface temperature.”

By their calculations, Betelgeuse’s average surface temperature on Feb. 14 was about 3,325 degrees Celsius, or 6,017 F. That’s only 50-100 degrees Celsius cooler than the temperature that a team — including Massey and Levesque — had calculated as Betelgeuse’s surface temperature in 2004, years before its dramatic dimming began.

Levesque said, “The study cast doubt that Betelgeuse is dimming because one of the star’s massive convection cells had brought hot gas from the interior to the surface, where it had cooled. Many stars have these convection cells, including our sun. They resemble the surface of a pot of boiling water.”

“But whereas the convection cells on our sun are numerous and relatively small — roughly the size of Texas or Mexico — red supergiants like Betelgeuse, which are larger, cooler and have weaker gravity, sport just three or four massive convection cells that stretch over much of their surfaces.”

In recent weeks, Betelgeuse has begun to brighten again, but slightly. Regardless of whether the current dimming wasn’t a sign that the star would soon explode, to scientists, that’s no reason to stop observing.

Levesque said, “Red supergiants are very dynamic stars. The more we can learn about their normal behavior — temperature fluctuations, dust, convection cells — the better we can understand them and recognize when something truly unique, like a supernova, might happen.”

The paper is accepted to Astrophysical Journal Letters.